By Charles Adams

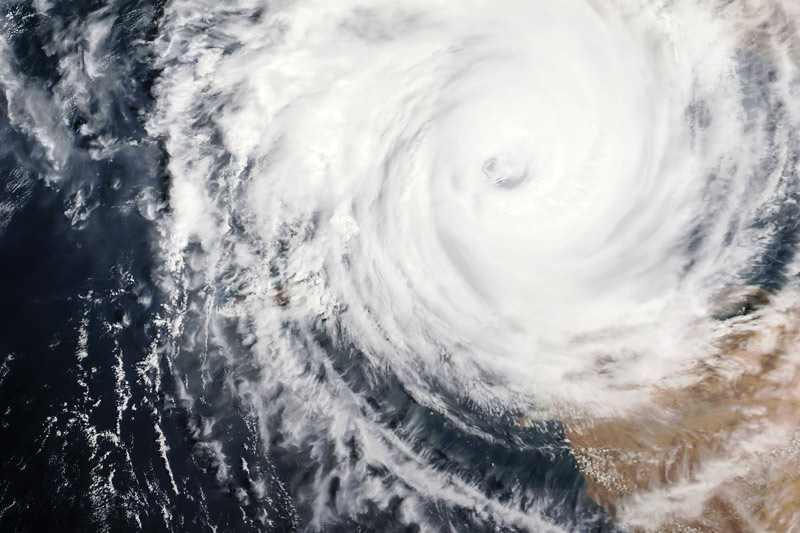

The 2017 Atlantic hurricane season has been all over the news recently, and the curious among us may naturally wonder why the Pacific Northwest is spared such devastation. The Pacific Northwest is no stranger to gales of tropical storm force (34 knots) or greater, however, the region is rarely affected by exotic meteorological phenomenon such as hurricanes. Cyclones, hurricanes, and typhoons all refer to an organized weather system originating in tropical to sub-tropical waters and characterized by closed low-level circulation. In the northwestern Pacific, the storms are called typhoons; in the Indian Ocean, they are called cyclones or cyclonic storms; and familiarly in the Atlantic and northeast Pacific, they are called hurricanes. The northeast Pacific generates approximately 16 named storms per year, while the Atlantic produces on average 10 and yet, western North America usually ends its hurricane season impact-free. The main heroes protecting our coast are cold water and prevailing winds.

One key ingredient to hurricane formation is a water temperature above 26.6°C, which is typical for the equatorial Atlantic year-round. Water temperature is important because a hurricane is like a giant heat engine fueled by warm moist air, which produces wind and wave energy. If you remove the fuel (warm water evaporating into the air) from the engine, the system will collapse and the storm will dissipate. In the northeast Pacific, the California Current flows south from Alaska, feeding 15-20°C water toward the equator. While this current makes the water too cold for leisure swimming (excluding a few brave souls) throughout most of the year, it serves to inhibit storm formation near the coast and drastically weakens any hurricane that strays too near.

In both the Atlantic and Pacific, tropical storm generation typically occurs near the equator, with the storms trending in an east to west direction. This generalization is a result of the prevailing trade winds that blow east to west between the equator and 30° N and 30° S latitude. Storms in the Atlantic can develop anywhere near the equator between Africa and North or South America. After formation, Atlantic hurricanes can feed off the warm tropical waters in the Caribbean or Gulf of Mexico/Gulf Stream, continuing westward until they dissipate at sea (called a “fish storm” because they only impact fish) or make landfall on a coast. In the Pacific, storm generation occurs as far south as Panama, with storms tracking east to west. However, due to the size of the Pacific and lack of continents or populated areas west of their formation, these northeast Pacific storms tend to only affect shipping traffic and the more adventurous sailors.

Both the cold water and trade winds inhibit hurricanes from impacting the coast north of California. However, the West Coast is frequently the target of “leftover” hurricanes that have transitioned into extratropical storms. These storms are accompanied by torrential rains and frequently Category 1 hurricane-force winds. While we cannot escape the weather, model forecasts are becoming increasingly accurate in their predictions of storm direction and impacts, yet sometimes the most accurate forecast you can find simply involves taking a step outside.

The cold water and prevailing winds may be primary causes of our grey skies for half the year, but that’s just the price of a hurricane-free boating experience. Worth it?