adventure after another.

My first Vic-Maui race was in 1984 aboard Hypertension, a Baltic 42 owned by Roger Palmer. I was 19 years old, and I recall turning 20 during the race. What I didn’t know in that moment was that I would go on to compete in eight more Vic-Maui’s, nine if you count this year (starting July 1). At that time, I was leaving on a great adventure and my buddy Erik Klauss was on board as well. It was us two “kids” and then a group of six other adults— “old guys”— in their 30s and 40s!

My first Vic-Maui race was in 1984 aboard Hypertension, a Baltic 42 owned by Roger Palmer. I was 19 years old, and I recall turning 20 during the race. What I didn’t know in that moment was that I would go on to compete in eight more Vic-Maui’s, nine if you count this year (starting July 1). At that time, I was leaving on a great adventure and my buddy Erik Klauss was on board as well. It was us two “kids” and then a group of six other adults— “old guys”— in their 30s and 40s!

There is nothing like leaving shore behind to do your first trans-oceanic race. Those who are about to embark on the upcoming Vic-Maui race know the feeling. You are nervous about what is to come, and questions fill your head. Will I get seasick? Will I get enough sleep? Will the food be good? What will it be like away from everything and everyone for two weeks?

I’m sure it’s different for everyone, but for me there was nothing like it. I’ve read past blogs from previous races and without fail, I mention that I forget on shore what it’s like to be out there until I get back out. It’s special; it’s epic. There is something different about being on the water with no distractions, for the most part, no phone, no work, just you and seven other crew members sharing the experience. It’s awesome. Oh yes, there is the part that sucks, too.

In the 1984 race, the not-so-fun part made itself all too apparent very quickly. We ended up off the northwest Washington coast slopping around in no wind and big waves. That was my first experience with the dreaded Mal de Mar – seasickness. And oh, was I seasick! So was half the crew, barfing over the side. It took a couple of days to find my sea legs.

That ‘84 race was special. I experienced things that I had never seen and done before. I remember once we got going, a huge number of Velella velella (a jellyfish variant) appeared. Also known as by-the-wind-sailors, they are small oblong jellies with a sail on top. The ocean was so thick with jellies that it looked like you could step off the boat and walk on them.

We were also on a boat with guys who knew how to have fun. We fished, catching mahi mahi and tuna, and I remember something hitting the line so hard that it nearly tore the stern pulpit off! In that race we ended up beating in 30 knots of wind for a couple of days. I recall driving with two reefs in the mainsail and the #3 up. At night, all we had to look at was the binnacle compass and sometimes it appeared to suddenly start spinning, but it was just hallucinations as I started to fall asleep. When that happened, it was time to make a change at the helm!

The beauty of a Vic-Maui race is it just keeps getting better as you head south and get into the trade winds. The lousy conditions that can and do happen at the beginning of the race are typically forgotten on the second part of the race as you sail downwind with the spinnaker up and the temperature getting warmer and warmer. When you eventually spend that first night in shorts and a T-shirt, you know you have arrived. I remember that during the ‘84 race as it got warmer, I’d look at the sky at night, listening to the Rolling Stones over and over. We saw dolphins, whales, and the ever-present albatross. We had a great time, partied a fair amount, and finished dead last in our class, but I’ll always remember it. I was truly hooked.

I did the race again on Hypertension in 1986, then three times aboard the Beneteau 45F5 Farr-ari in ‘94, ’96, and ‘00. I raced in 2002 aboard the J/145 Jeito (more on that in a bit), aboard the J/130 Voodoo Child in 2004, and aboard a Santa Cruz 52, also named Voodoo Child, in 2006. My most recent race was aboard the J/145 Double Take in 2012.

We had good success on the Beneteau 45f5 Farr-ari, owned by mad dog Englishmen Bill Walton. We finished second in class the first time out and won our class the next two outings. I served as navigator for those three races, and thought I was hot stuff by the finish of that third race.

Then came the 2002 race aboard the J/145 Jeito. The fleet that year pretty much acknowledged that we were the boat to beat, and as it turns out everyone pretty much beat us! We finished two days behind the winning Santa Cruz 52 Mystic, which was tough since I believed we owed them a couple hours. I decided that if I was going to finish like that again, it wouldn’t be because I didn’t know what I was doing. That’s when I like to say my real education began when it came to weather and understanding weather. But more importantly, it was in using the tools that were available for navigators. Yes, I’m talking about weather routing software.

In the 2004 race on the J/130 Voodoo Child owned by Brian Duchin, we used Deckman for Windows weather routing software and it was a very powerful tool. That year we were in the fast class and did something that none of the other boats in our class dared. We sailed west of rhumb line, where we crossed a ridge of high pressure and moved in to west-southwest flow. We did this while the rest of our class sailed due south and around the bottom of the ridge.

We easily sailed 200 less nautical miles and in more breeze. The downside was we had to sail with wind forward of the beam and spent more time with a headsail up. We finished first in class and second overall. I’d never have done that route if the software hadn’t pointed the way. It turned out to be the right way to go.

The next race was the 2006 run aboard the Santa Cruz 52 version of Voodoo Child. Again, we used Deckman for Windows. We were the first to finish and won the race overall. The weather routing software told a very different story from the previous race. This time it had us jibing back towards land off Northern California to get into a higher pressure gradient. The software said the same thing repeatedly, so we did, and it paid off. I’ll never forget being halfway to Hawaii when we crossed paths with Cassiopeia, a Davidson 74 that owed us nearly two days.

Here we were halfway into the race and we were dead even with a boat that owed us two days. We sailed nearly 100 extra miles, but it was worth it. Later, Cassiopeia lost the top part of their mast in a jibe and we found ourselves first overall. The point is—trusting our routing software played an instrumental part in our overall success.

My last race in 2012 was aboard Double Take, a J/145. This boat was owned by my close friend Tom Huseby, who also had owned Jeito, which finished last in class back in 2002. We were back.

The 2012 race on Double Take couldn’t have been more different than the the one aboard Jeito ten years earlier. Back then, I’d sailed us too close to the high and we were literally stuck for two days. We broke lots of stuff aboard, including the steering cables and a 2A running spinnaker.

In 2012, we had no such issues. I honestly don’t remember breaking anything. This time around we used Expedition weather routing software. We killed it, finishing first in class, first overall, and first to finish in elapsed time. We shaved four days off our 2002 trip, finishing in ten days and change as opposed to 14 days and change. We came back with many of the same Jeito crew in 2012 and turned it completely around.

So, what does it take to be successful in a Vic-Maui? First off, you must decide what success means. For many of the racers, success often means getting there in one piece without anyone hurt. For them, teamwork and experience is enough. Others will be going for it, attempting to win.

Winning overall can be elusive and sometimes just not in your control. Take the last race in 2016, the TP 52 Valkerie set the elapsed time record, and another TP 52, Kinetic, won on corrected time overall. These were the last boats to start, and it’s arguable that the last start also had the best conditions over the entire course. It could have gone another way, though. A very well-sailed boat, Rain Drop, could have easily won overall if conditions had favored the early starters. But Rain Drop sailed in very light conditions early on, and it just wasn’t in the cards to be in the running for the overall.

To be successful in a Vic-Maui takes a combination of things. One of the more important is the preparation prior to leaving the dock. In every Vic-Maui race there are failures. Typical failures are steering as cables break (remember how I said the steering broke on Jeito?), or issues with bearings or halyards, or chafe in general.

The boat’s not fast if a spinnaker halyard breaks and the spinnaker goes in the water. A final point to note is battery charging issues. Every year some of the boats have an issue with being able to charge their batteries. Many of these problems can and should be addressed prior to leaving the dock. Any time you lose during the race is a loss to your chances of winning. Time lost can’t be reclaimed and is deducted from your final time. The well-prepared boats will have mitigated or lessened the chance of equipment failures.

Another contribution to success is the people you bring with you. And I don’t necessarily mean having the best sailors. Sailors that are good shipmates are just as important and, I’d venture to say, more important than having the best sailors. I can’t stress this one enough. It’s very important to have a compatible group of sailors getting along and all working hard. Part of my pre-race speech goes something like this: “As long as we all do 110 percent of what is expected, then it will all work out great.”

This means if something needs doing, get it done, and don’t let it fester. Clean up after yourself, do the dishes, pack a spinnaker, and get up if you’re on the on-watch group. These sorts of things make a huge difference. It is very distracting to the group if someone obviously isn’t pulling their weight; if they are hard to get along with, it will severely detract from the experience.

If you plan to do this race and there is someone you are thinking of bringing along that has a few questionable personality traits that pop up now and then, just remember these traits will likely amplify offshore when sleep deprivation sets in along with other discomforts that can come from doing a marathon like this.

Finally, having good sailors is key. It’s very important that at least half the crew at a minimum are good drivers, more is even better. It is particularly important to have experienced night drivers, folks who can keep the boat on course and moving fast. Sails trimmed properly with the right sail up is equally as important. Again, remember that any time lost is not retrievable, and the boat that has the shortest amount of downtime is likely going to be the boat that wins.

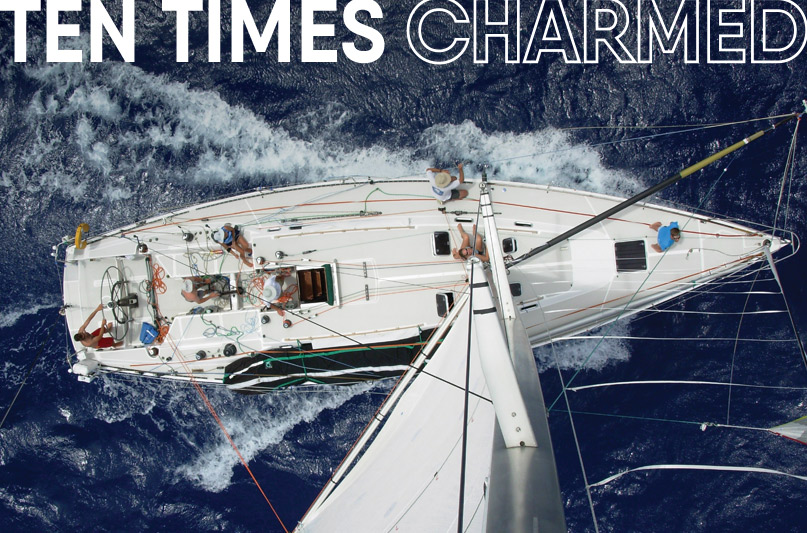

I realize that 2018 will be my tenth Vic-Maui Race. For this year’s race, I’ll be aboard a Morris 45 named Firefly. You might call Firefly a wolf in sheep’s clothing. This is a very fast 45’ cruising boat that has a lot of sail and an underbody to match. We have discovered just how fast. In the last two races, we finished first for the Vashon Island Race and third in a very competitive class during Swiftsure. Our ORC rating reflects the wolfishness of this boat. We are the fastest boat in the first start and we owe the next boat, the very well sailed J/122 Joyride, just over 11 hours! We will have our work cut out for us, that is for sure.

I do feel that we are one of the better prepared boats on the course, with the opportunity to do well. I will probably be learning the truth on the water during the race as you read this. We have the sails, gear, and preparation to help put us into a position to do well. The crew is a mix of first-timers and offshore veterans. The first goal is to be safe and to get to Hawaii with the same number of crew we left with. The second goal is to have fun. Heck, that’s why we do this —to have fun, enjoy the moment, and remember the adventure. The third goal is to win. Winning is an important part, but honestly, I’d rather be safe and have fun over winning. Wish us luck!

Read the full story on Issuu