In 2007, Seattle area residents started hearing about Colton Harris-Moore, a small-town kid from Camano Island who turned mischief into a seemingly unending crime spree that caught the nation’s attention. Eventually dubbed “The Barefoot Bandit,” Harris-Moore became a Northwest legend and, eventually, an internationally known criminal.

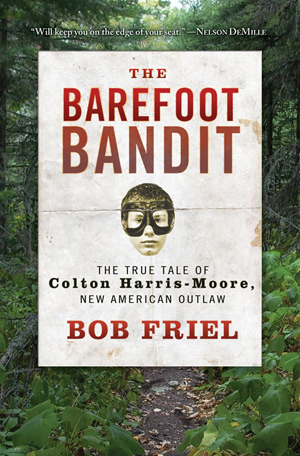

Bob Friel’s book, The Barefoot Bandit: The True Take of Colton Harris-Moore, New American Outlaw, might seem a strange selection for yachting enthusiasts, but it is our complicated nautical playground that truly gave Harris-Moore the cover he needed to remain at large and wreak havoc on local homes and businesses. While the media marveled at his ability to steal and fly airplanes (landing was another issue he never quite figured out), Harris-Moore’s proclivity for stealing boats and navigating the waters of the northern Puget Sound and San Juan Islands is equally astonishing.

Most of us have found ourselves turned around or confused in the maze of waterways in the San Juans. Armed with charts, guidebooks, and GPS, it is still remarkably easy to find yourself approaching an unmarked rock or stuck in a bad rip current. It is even easier to accidentally run into a deadhead floating in the dark, cold water. Currents in the channels run fast and can toss a small boat around easily. Colton Harris-Moore was still able to steal several boats in the San Juans and get from island to island without being detected or caught, often in the dead of night. Even with my radar and chartplotter doing their jobs, I am reluctant to make nighttime crossings in the islands, an area I have been cruising for over 20 years.

When I spoke with Bob Friel recently, he had this to say about Colton’s ability to navigate here. “(When I moved here it) meant a steep learning curve to safely navigate these rocky and sometimes tricky waters. So to see Colton again and again jump into unfamiliar boats, always in the dark of night, and not only run around the San Juans, but also over to the mainland, back and forth from Island County, then across the Columbia River, and then to follow his midnight maritime exploits in the Bahamas, and see him survive, was remarkable.”

Reading about Colton’s crime spree reminds me that the San Juan and Gulf Islands were (and still are) a smuggler’s paradise long before they were the cruising destination of choice for boaters from all over the world. Cold, dark water and miles of unwatched shoreline make it a fairly easy place to get lost if one wants to. Colton wanted to stay hidden, and he used the cover of the islands to make it happen.

Part of his success was taking advantage of Northwest boat owners’ legendary trust of others. Especially in the summer, we leave our hatches unlocked and open. Most of the boats on my dock have the same ridiculous code for their padlocks (it rhymes with hero, hero, hero, hero).

Beyond that ease of access to boats, however, is what must be a natural sense for navigation and piloting. If you gave me an unfamiliar boat on a dark fall night and told me to get from Orcas Island to Friday Harbor without being detected, I give myself a 60/40 chance of making it unscathed.

Harris-Moore started stealing dinghies on Camano Island early in life. As Friel tells it, Colton’s fascination with the sea led him to boosting tenders in front of beachfront houses, often swapping engines with nearby boats to create his own perfect cruising combination. He would zip around in his newfound craft until he ran out of fuel or the engine died – at least once he used the wrong fuel in a two-stroke engine.

Then, more often than not, he would leave the boat near where he took it. The kid grew up on an island and had endless access to the beach (and no supervision to reign in his adventures), but he knew the real freedom was on the water and in the air, not on the beach.

I followed the “Barefoot Bandit” case closely while it was happening, but Friel’s book details the young man’s life and exploits in a perfectly paced, incredibly informative narrative. He doesn’t bog the storytelling down with unnecessary detail, and he is constantly walking an edge between admiration and disdain for Colton.

When I brought up this conundrum with Friel, he said, “Of course, what Colton did was wrong, and he spent a big chunk of his prime young years in prison because of it. He’s already paid off about 90% of his restitution, though, and if the plans he tells me about ever come to fruition, I wouldn’t be surprised to one day see Colton cruising up to the Deer Harbor dock in a boat that’s actually and legally his.”

When I brought up this conundrum with Friel, he said, “Of course, what Colton did was wrong, and he spent a big chunk of his prime young years in prison because of it. He’s already paid off about 90% of his restitution, though, and if the plans he tells me about ever come to fruition, I wouldn’t be surprised to one day see Colton cruising up to the Deer Harbor dock in a boat that’s actually and legally his.”

We can argue endlessly about how Harris-Moore was treated by the press. We can discuss whether he should be treated as a cult hero or a criminal. The book doesn’t force you to make that choice. At the end of the almost 400 pages of narrative, you are left with a portrait of a smart but troubled young man who got so far down the wrong path that he didn’t see a way to turn around. In his eventual arrest in the Bahamas, we see a tired, broken human being who somehow managed to pull off one of the most impressive crime sprees in modern history.

I bought a copy of Friel’s book on impulse at the little Dock Store in Deer Harbor, a fitting happenstance given that so much of Harris-Moore’s thefts took place on Orcas Island. Bob Friel lives nearby and keeps his boat moored at Deer Harbor. All of us onboard my boat that weekend raced through the book as we cruised the same waters that Colton used for transportation and cover from the authorities.

It is and will remain one of the more remarkable legends of the Northwest. The newest edition of The Barefoot Bandit is available with updates and corrections on Kindle.