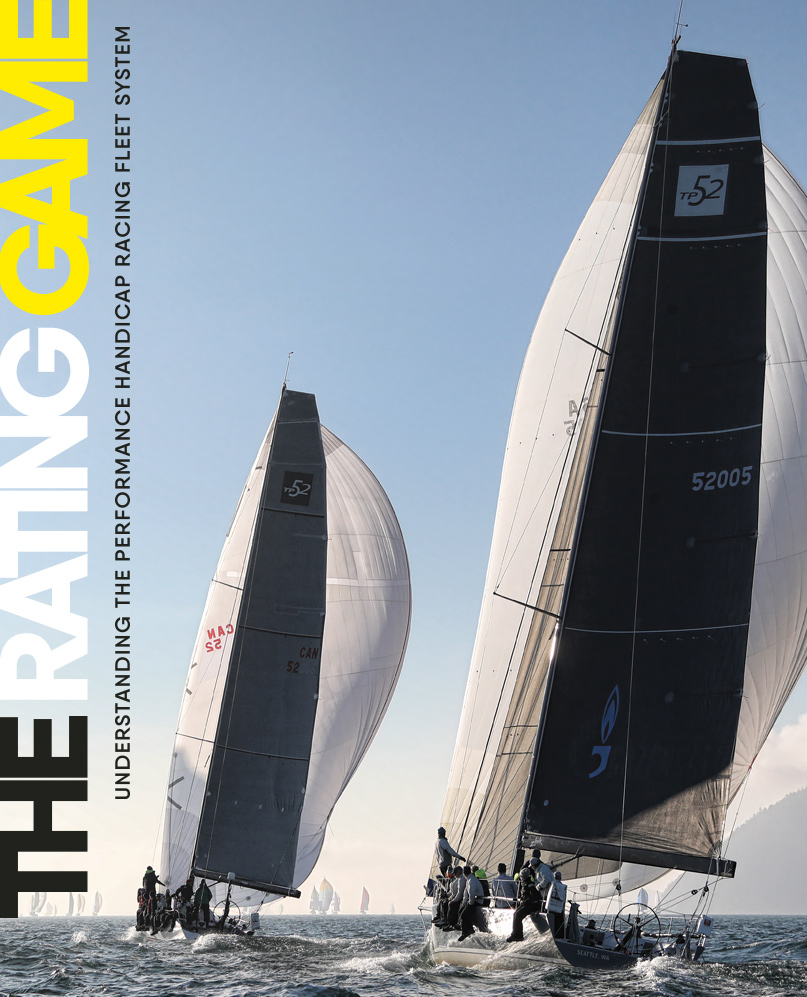

It doesn’t get much better than going out for a pleasant race on a sunny Sunday afternoon with friends and/or family. Still, racing is racing. No matter how you look at it, it’s still a competition and your goal is to try to beat the next guy and have the bragging rights back at the club.

It doesn’t get much better than going out for a pleasant race on a sunny Sunday afternoon with friends and/or family. Still, racing is racing. No matter how you look at it, it’s still a competition and your goal is to try to beat the next guy and have the bragging rights back at the club.

Racing in a One-Design fleet is the easiest and, all things considered, the most up-front methodology. In a One-Design class, you know what place you’ve finished in as soon as crossing the line. This competition also tends to be closer due to the similarities of the boats. After all, everyone in the field is exploiting the same boat’s abilities.

More often than not, however, we find ourselves racing against a mixed bag of boats. Cruisers, sport boats, big boats, small boats, how do we really know where we stand?

Some boats are lighter and faster than others, some are better off the wind, and some excel in lighter conditions. At the end of the day though, we still need to figure out where we finished. How did we do?

Here’s where a handicapping system comes into play – and because those systems can be a bit arcane, it’s important to know how they work. The most common and popular system is PHRF, which stands for Performance Handicap Racing Fleet. It’s fairly simple and inexpensive, making it ideal for the casual and serious racer alike.

There are many different handicapping systems that suit a wide variety of needs. They will fall into one of two main categories; performance-based or measurement-based. PHRF is mainly performance-based. A handicap for a particular boat begins with a base number that has been determined by observing individual designs over a period of time to determine how they stack up against other designs.

Your boat may be different than that “base” boat, so a qualified handicapper will review your application to determine how your boat may differ. For example, you might have smaller sails, or a fixed or a feathering propeller. In any event, to attain your proper handicap you must join your regional PHRF organization – they need to size you up and set up a fair field.

The number you are ultimately assigned represents an amount of time in seconds. Pretty simple, the lower your number, the faster you have been rated. At the end of the race, the elapsed times for each boat are fed into a scoring system and calculated along with each boat’s handicap, and voila, we have our results!

These are often posted after a certain amount of revelry has already taken place, which brings us to the first of the flaws in the system. Suspicion!

If you’re realistic, you’ll look at your results and simply say, “We just have to do better next time.” Or maybe you won, in which case there’s no suspicion. The system seems to be performing as it should. But there is always a certain element of doubt, especially in a performance-based system like PHRF.

If you find yourself having consistently poor finishes, human nature dictates that one of your concerns will be whether your boat has the right handicap or not. A good thing about PHRF is that you do have the right of appeal.

While handicaps are sometimes adjusted for an entire fleet of One-Design boats, more often than not, it is up to you to provide your reasons, submit your appeal and wait for the handicapper’s council of your regional association to decide. Often the result can be disappointing, and you go back to being suspicious.

It’s important to understand how a handicap is determined. It is based on the optimum scenario, that your boat has a clean, freshly painted bottom, crispy new sails, all equipment operates smoothly and efficiently, and of course, you and your crew are expert sailors.

Before you let your suspicions get away with you, it’s important to ask yourself “Have I really prepared my boat the best that I can, and am I sailing to its handicap effectively.” Sorry to be honest, but most of the time that answer is “No.”

Another flaw is that PHRF has not kept up well with the advent of newer, lightweight designs since its inception in the early 80s. We’ve all been out there and had that feeling that everything is going great—the boat feels good, the crew are happy, the skipper is feeling large—until we round the top mark, the sport boats skip up onto a plane, and they’re gone!

To add insult to injury, the sport crews end up with the best seats in the bar at the end of the race. The best we can hope for is that they haven’t eaten all the nachos too!

Really the sport boats should be racing in a One-Design division on their own, which would undoubtedly be their preference too. However, most of the time there are not enough numbers to allow for that, so they get lumped in with mom, dad and the kids in the Catalina 30.

Over time, improvements have been made to the system to address some of the issues that have been identified. In the early going, the calculation of your corrected time for a race was based on a “Time on Distance” model (ToD). This method did not account for issues like

a dying wind or a change of current during a race. It also relied on race organizers measuring the distance of the course accurately.

Eventually the “Time on Time” model (ToT) was developed. Instead of calculating by the course distance, results are calculated by a time correction factor.

Simply put, this method addresses some of the shortcomings of the ToD method, and experts will tell you that ToT is the fairer approach.

For most boat owners, PHRF is a simple and inexpensive, if slightly flawed, way to allow us to go out and have some fun racing. If you understand its shortcomings and manage your own expectations appropriately, it is all most of us require for racing. On a different level, there is the issue of how race managers, clubs, and event organizers apply PHRF.

Most of us started out by joining in our club’s beer can race program. There we have a mix of casual and novice racers mixed in with the local rock stars. It can be a little deflating for those less experienced to never reach the podium, so it’s important that clubs themselves come up with a way to keep the newbies engaged. After all, they might become the rock stars of tomorrow, and everyone needs a little glory moment from time to time to hold their interest. Within the confines of your own club racing program there are options.

You can assign your own club-level handicaps to account for experience or lack thereof. Even better, you can use a golf-style handicapping system where individual handicaps change after every race based on how well each boat is performing. This is not at all difficult to do and US Sailing, which owns PHRF, has an excellent dissertation on their website on how to do this effectively.

It is most important that once you leave your club and venture out into larger regional events, you must have a valid handicap obtained through your regional PHRF organization. You’ll also need to maintain the currency of that handicap by keeping up with your annual membership dues.

Unfortunately, it has become an all too common practice at some events to allow entry to boats that do not possess a valid handicap. Instead, the regatta gives them an arbitrary handicap. More entries mean more revenue for the regatta. I get that, but arbitrary handicaps, given often by one person who has only a modest understanding, circumvent the proper handicap assessment your regional authority can provide. The arbitrary handicap may be well off the mark and gives an unfair advantage or disadvantage. That erodes confidence in the fairness of the formula.

Imagine yourself as a longtime PHRF member racing in a regional championship that you’ve put energy and effort into, only to lose to a boat that just showed up and was given an arbitrary handicap! It will not give you a warm, fuzzy feeling about the regatta and you may not return next time. Event organizers beware! You could be chopping yourselves off at the knees!

US Sailing, as the owners of PHRF, sanction individual PHRF organizations to assign handicaps within their area. There are about 60 PHRF fleets in North America and US Sailing allows for a certain amount of autonomy between fleets to allow for local variations in racing conditions and such.

In the Pacific Northwest up to the early 1990s, there was only the PHRF-NW serving the entire Pacific Northwest region. This became an issue around that time.”

Some influential sailors in British Columbia grew dissatisfied with PHRF-NW, not entirely without reason, and split off to form PHRF-BC. At the time, only the mainland BC clubs went with them. The clubs on Vancouver Island elected to stay with PHRF-NW. This was due in large part to the concerns about how the split could negatively affect the popular Swiftsure Race, which originates in Victoria each year.

Over time the two organizations drifted apart in their approaches. Some boats had much different handicaps in one fleet than in the other, which became a big problem where the two systems collided at regattas like Round the County. Increasingly, the sailing community insisted on greater fairness, which led to normalization of handicaps.

Events would identify themselves as either PHRF-NW or PHRF-BC regattas and boats from one fleet had their handicaps adjusted to match those for similar boats in the host fleet. Needless to say, this is a time consuming and entirely thankless task for regatta organizers. It’s also very likely that various regattas have lost some racers altogether due to dissatisfaction with this issue.

The responsibility for resolving this problem does not rest with the individual racer or with the event organizations either. This issue rests solely with the two PHRF organizations to resolve through a harmonization of the two systems.

So what should “harmonization” look like?

There is no reason not to have two PHRF fleets, one for either side of the border. Individual member applications and appeals can be better served this way. Each organization can assess their own dues model. Individual racers can choose which fleet to join, provided that the playing field is level across the region.

Underlying the two organizations should be a collaborative process to address issues common to the entire region. The methodologies of arriving at a boat’s handicap should be the same in both PHRF fleets and there should be a common handicap database. Each organization continues to conduct handicapper’s council meetings, but there should be at least one joint annual conference between the two to ensure they are serving together the interests of PHRF racers in the Pacific Northwest.

I’m happy to say there appears to have been some movement in this direction, but much work remains.

The moral of the story is that PHRF will always, and should always, have a place in our racing community. Even with the ebb and flow of different systems of measuring variations between boats, PHRF remains one of the simplest and most economical approaches to keeping things fair and fun for a wide spectrum of racers.

Ultimately, the goal should be promoting fair and equitable racing and encouraging the overall health of the sport we love.