Over the last decade, I’ve been privileged many times to be aboard the Royal Canadian Navy ship that establishes one end of the Swiftsure International Yacht Race’s start line. The ship anchors off Victoria’s Clover Point, a small thumb of land jutting out into the Strait of Juan de Fuca. To the south of the anchorage, the snow-topped Olympic Mountains create a majestic backdrop. Swiftsure, the largest yacht race on North America’s Pacific Coast, is a rugged, exacting, colorful, international competition. Winds can be brisk, or it can be a frustrating “Driftsure.” Occasionally, after the start, the flooding tide can sweep boats back way past the start line—as far back as San Juan Island.

Over the last decade, I’ve been privileged many times to be aboard the Royal Canadian Navy ship that establishes one end of the Swiftsure International Yacht Race’s start line. The ship anchors off Victoria’s Clover Point, a small thumb of land jutting out into the Strait of Juan de Fuca. To the south of the anchorage, the snow-topped Olympic Mountains create a majestic backdrop. Swiftsure, the largest yacht race on North America’s Pacific Coast, is a rugged, exacting, colorful, international competition. Winds can be brisk, or it can be a frustrating “Driftsure.” Occasionally, after the start, the flooding tide can sweep boats back way past the start line—as far back as San Juan Island.

I’m delighted to hang over the ship’s bulwarks, watching from above the more than 200 sailboats participating in the race every year. Competitors come from British Columbia, Washington, Idaho, Oregon, and California. They duel with a cornucopia of vessels—sloops, ketches, the occasional yawl, a schooner or two, catamarans, and trimarans. Mostly they’re made of fiberglass, with a few cold-molded hulls, even some classics built of wood.

I’m delighted to hang over the ship’s bulwarks, watching from above the more than 200 sailboats participating in the race every year. Competitors come from British Columbia, Washington, Idaho, Oregon, and California. They duel with a cornucopia of vessels—sloops, ketches, the occasional yawl, a schooner or two, catamarans, and trimarans. Mostly they’re made of fiberglass, with a few cold-molded hulls, even some classics built of wood.

As they mill about awaiting the start of one of the five races they’ve signed up for (six in 2018), it’s amazing how such a throng of boats– sails raised, the use of engines outlawed– avoids colliding. The boats juggle, jockey, and slither narrowly past each other, jostling within inches of competitors. The sails, lit by a blazing sun, are magnificent—pure white, traditional red, silvery gray, golden, black. The boats are filled with lively crews, in colorful foulies, their adrenaline high.

Then, a loud blast. The naval ship lets off a canon shot, signalling the start of a race. Whitish smoke wafts over nearby sails. The first group of racers is off!

In 2018, Swiftsure will celebrate its 75th run on May 24 to 28. It wasn’t always smooth sailing, though. In 1930, six sailors from the Seattle (SYC), Royal Vancouver (Royal Van), and Royal Victoria (Royal Vic) yacht clubs figured it was time for a good race. Over a few toddies, they decided to race the following day from Cadboro Bay and round the lightship, Swiftsure (hence the race’s name), anchored on Swiftsure Bank. The Royal Ocean Racing Club rules were applied; and SYC’s “skimming dish schooner” Claribel won.

In 2018, Swiftsure will celebrate its 75th run on May 24 to 28. It wasn’t always smooth sailing, though. In 1930, six sailors from the Seattle (SYC), Royal Vancouver (Royal Van), and Royal Victoria (Royal Vic) yacht clubs figured it was time for a good race. Over a few toddies, they decided to race the following day from Cadboro Bay and round the lightship, Swiftsure (hence the race’s name), anchored on Swiftsure Bank. The Royal Ocean Racing Club rules were applied; and SYC’s “skimming dish schooner” Claribel won.

The following year, four yachts entered the event, with only one—Royal Vancouver’s Westward Ho—finishing the race. The Depression depressed racing—a single contest was held in 1934. During World War II, many sailors patrolled the waters to spot Japanese subs; racing wasn’t considered patriotic.

But in June 1947, with post-war optimism blooming, 15 yachts, using the Cruising Club of America handicap system, lined up near Brotchie Ledge and began an annual tradition that hasn’t flagged since. Between 1948 and 1950, the race started in Port Townsend to bypass the notorious Race Passage currents, but in 1951 the Royal Victoria Yacht Club became the permanent host. The race has started off Victoria ever since. Over the years, Swiftsure grew to attract as many as 400 competing boats, then settled back to a couple of hundred annually. The choice in 1960 to hold Swiftsure on the U.S. Memorial Day weekend helped attract boats coming from afar.

to round the mark for the Classic Race.

The traditional course is the Swiftsure Lightship Classic (138.2 nautical miles [nm]), but other courses were added as interest grew. By 1962, after many skippers felt their boats were too small to reach Swiftsure Bank, the race committee introduced a shorter race to Clallam Bay, 15 miles west of Port Angeles, calling it the Juan de Fuca Race (78.7 nm).

It proved a success, and by 1969, nearly 50 boats competed. The 1988 addition of the Cape Flattery Race (101.9 nm), falling almost halfway between the Swiftsure Lightship Classic and the Juan de Fuca courses, attracted many larger yachts. The Hein Bank Race (118.1 nm), introduced in 2015 (just 20 nm shorter than the Swiftsure Lightship Classic), gives great competition to larger, faster boats not wishing to stick their nose into the open Pacific.

Finally, the Swiftsure Inshore Classic, whose courses are determined for each race after reviewing weather and tidal current predictions, was added in 2004.

The first Swiftsure racers sailed on wooden yachts. These were generally reserved for the wealthy—the initial investment and the never-ending upkeep were outside the average family’s means. But the growing affluence of the post-war ‘50s and ‘60s, combined with the invention of fiberglass boat construction material, allowed less well-heeled people to own boats.

As Daniel Spurr wrote in Heart of Glass: Fiberglass Boats and the Men Who Built Them, “Indeed, were it not for fiberglass, hundreds of thousands of people, like myself, might never have taken to the water as we have… in everything from canoes to sportfishermen to sleek sloops and homely ketches.”

As Daniel Spurr wrote in Heart of Glass: Fiberglass Boats and the Men Who Built Them, “Indeed, were it not for fiberglass, hundreds of thousands of people, like myself, might never have taken to the water as we have… in everything from canoes to sportfishermen to sleek sloops and homely ketches.”

Along with changes in boat-building material, sails also benefitted from new tech. Our first Swiftsure racers used cotton or hemp sails. The invention of Dacron and nylon sails allowed sails to be much lighter and maintained a much better shape. Today’s carbon-fiber reinforced sails have produced an almost meteoric improvement, offering ever-higher performance, lighter weight, and greater stretch resistance.

Similarly, today’s sailors use cored synthetic lines that combine such materials as aramid fibre, Kevlar, Technora, and Vectran. They’re much lighter, tougher, and UV- and stretch-resistant than the old ropes made of hemp, cotton, linen, or jute. And they’re lots easier on the hands.

“I think the first Swiftsurers would also be impressed by the change in clothing,” said Ron Jewula, who has 25 Swiftsure races under his keel. “We wear lightweight, waterproof foul weather gear and drysuits. Breathable stuff with bright colors. Much better than the old, heavy, and uncomfortable oil slickers that made everyone look the same.”

Ron added that feeding a crew, especially on coldish overnight races, is much easier than in the past. “Most boats have a fridge, stove, and propane,” he said. “You can eat pretty well on freeze-dried food and keep up your strength.” He recalls the 2009 race when one of the crew was cooking while “the moon shone through the clouds. We had a beautiful run around the Navy ship on the Bank and a close-reach back. A textbook race.”

But the following year, no one ate a bite. “It was total slop,” Ron said. “We got within 10 miles of the Navy ship on the Bank at nine in the evening. Big waves, no wind, just sloshing around. Everyone was seasick. We finally got around the mark 12 hours later.”

But the following year, no one ate a bite. “It was total slop,” Ron said. “We got within 10 miles of the Navy ship on the Bank at nine in the evening. Big waves, no wind, just sloshing around. Everyone was seasick. We finally got around the mark 12 hours later.”

Modern electronic navigational aids have replaced the dead reckoning of the past. I can imagine the early racers gazing in wonder at today’s chart plotters showing the yacht’s exact GPS location, with radar overlay to boot.

Or reading the names of the freighters plying the Strait on AIS. Or seeing how hardware/software informs sailors when to tack, their boat’s wind direction and speed, the prevailing currents, and existing depths.

“These electronics allow us to continually play the tacks,” said Bob Bentham, who’s competed 17 times. “And now that SPOTs [race trackers] are carried aboard all long course boats, there’s no guessing where each competitor is located.”

Weather and winds. As Bruce Hedrick (formerly with Northwest Yachting magazine) told me, “Perhaps the reason Swiftsure is so popular is that no two races are ever the same. It’s said, in fact, that NOAA sends its weather forecasters to the Pacific Northwest to teach them humility.”

Besides the fickle weather, racers agree Race Passage always tests the best of sailors. The currents in the passage between Race Rocks and Vancouver Island’s rocks can reach 6 knots. The 2018 Swiftsure won’t be an exception—a strong flood will run until 15:48 hours on Saturday.

Besides the fickle weather, racers agree Race Passage always tests the best of sailors. The currents in the passage between Race Rocks and Vancouver Island’s rocks can reach 6 knots. The 2018 Swiftsure won’t be an exception—a strong flood will run until 15:48 hours on Saturday.

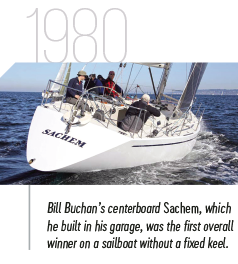

When tall racing tales are told, many of them focus on Race Passage mishaps. John Buchan, a long-time competitor, struck a rock in 1976 when returning in the fog. “We were bucking the tide and had no wind,” he recalls. “When we got jammed on that rock, I turned on the engine to get off.” He sailed on and won the race, only to be disqualified. “I had to turn on that engine for safety,” he said, still a bit disgruntled.

“We’ve sailed white-knuckled through Race Passage,” said Ron Jewula. “It’s the intensity of navigation. Lots of boats have nailed one of those islets here. Yet it’s an adrenaline high when you’re screaming through the Passage at midnight even when you’re tired and goofy.”

This year’s contest introduces the Legends of Swiftsure race, an inshore day-race for boats built in 1967 or earlier. Boats that haven’t raced any of the Swiftsure long courses since 2010 may also enter this contest. In addition, a one-design Six Metre race is planned for the Inshore course. And, as so many multihulls are now entering Swiftsure, a Juan de Fuca Multihull race has been added.

Swiftsure is hoping that retired U.S. Navy Rear Admiral Robert McLinton will be able to join the race in May. In 2016, at age 90, he was the oldest skipper to compete. When I spoke with Bob, who resides in Sequim, he said he’ll come if he can sell his J/35 Intrepid and replace it with a J/105.

I asked him what has contributed to such a long sailing life. His Annapolis Naval Academy training started his 39-year waterborne career, but he’s also biked from Los Angeles to Boston and from Swartz Bay, B.C. to Mexico, for a total of 24,000 miles. He’s proud his rides raised $51,000 for charity. The exercise and dedication have kept him sailing and in good shape. If any Northwest Yachting readers can help Bob switch boats so he can compete in Swiftsure at age 92, give him a shout!

The race’s 75th iteration is shaping up to be yet another memorable one. For those curious about more details and the latest developments, the event’s official website is a great resource (swiftsure.org).