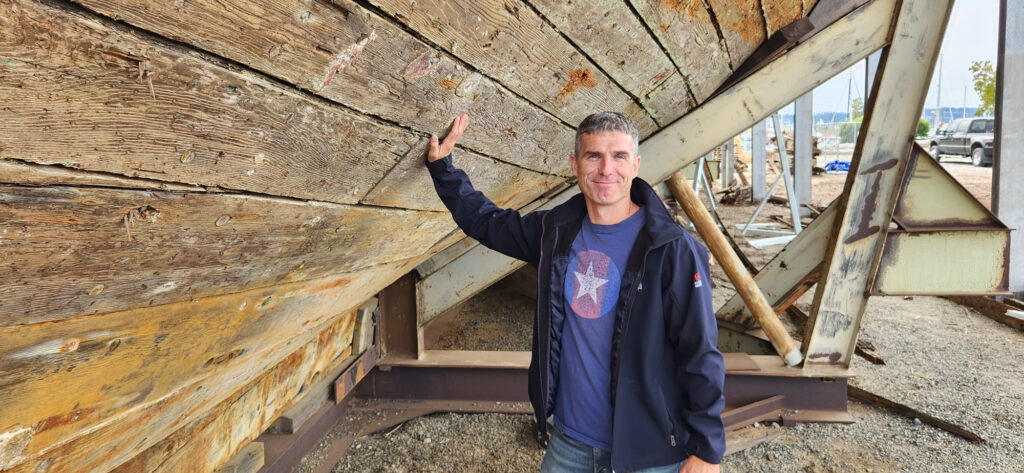

Piotr Bojakowksi, assistant professor for Texas A&M University’s Nautical Archaeology Program, was describing his keen interest in the historical significance of a famous maritime relic on the Everett waterfront. He had to raise his voice, however, to be heard over the racket made by demolition equipment that was ripping apart the same relic before his eyes.

“It’s the last remaining sailing schooner of its kind,” he said, as crewmen used a handheld pneumatic jack to pry another board off the weathered hull. “Once they finish dismantling it, there will be no other ship like it in existence.”

As residents of Everett, Washington, and local maritime history buffs may already know, the former schooner and converted tugboat Equator disappeared this fall from the 10th Street shed in which it sat for more than 30 years. With stints as a majestic sailing trader, a work-a-day tugboat, and a recovered piece of nautical history all playing parts in its century-long backstory, the Equator has reached the end of its long life, and now being separated into warehoused piles of timber and hardware.

But Bojakowski’s tone on that September day was not melancholy. The effort to save the moldering ship was fought and lost decades ago. Instead, he was excited for the rare opportunity he and his colleagues had to learn more about a poorly understood element of shipbuilding history.

“For a lot of wooden ships of the era, there is not much documentation about how they were actually built,” Bojakowski said. “It’s a one-of-a-kind opportunity to strip the planking, see the framing system, and quickly record it.”

Over the last few months, Piotr Bojakowski and his wife, Katie Custer Bojakowski, also a nautical archaeologist at Texas A&M, have thoroughly inspected, scanned, and cataloged the entire hull of the ship. Local demolition contractor Gonzo Boat Works then carefully dismantled the entire structure this fall so that the remains can be sorted.

Using LiDAR (light detection and ranging) scanners, photogrammetry, and 3D modeling software, the Texas A&M team is now determining how every plank, every bronze nail, every strip of caulking was pieced together more than a century ago. “Since we couldn’t preserve the ship, at least we can preserve the data,”Bojakowski said.

The Port of Everett, having taken over custody of Equator through Washington’s Derelict Vessel Program in 2022, is working on an interpretive display about the vessel’s storied history. It is also donating several pieces of the ship to a local artist, who plans on transforming the ancient wood into sculpture.

“It’s a unique partnership between the archaeology team and the contractor, as well as with the artist,” said Garrett Jensen, associate port planner for the Port of Everett. “There’s no real guidebook on how to take one of these boats apart or document a historic vessel, so this is also very helpful for the researchers themselves.”

Born and Born Again

Most working ships undergo multiple overhauls and reconfigurations across the decades, but the story of the Equator is remarkably long and eclectic. Built in 1888 in Benicia, California, by famed West Coast boat builder Matthew Turner, the Equator began its career as a two-masted, 81-foot pygmy schooner that plied the South Pacific trade routes.

Today’s examples of Turner ships only exist in fragments or drawings, which makes the intact Equator catnip for marine archaeologists. “This specific ship is probably the last surviving one built by Matthew Turner,” Bojakowski said. “Turner was considered one of the most prolific shipwrights on the West Coast. The framing he used was an art.”

In its first decade, the Equator’s most notable achievement was having a world-famous passenger. Novelist Robert Louis Stevenson, author of Treasure Island and The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, chartered a voyage from Hawai’i to the Gilbert Islands on the Equator from 1889 to 1890.

Even at this early stage in Equator’s life, it was an outdated vessel, as most wooden sailing ships were being converted over to coal-powered steam engines. “No one wanted sailing schooners for cargo anymore,” Bojakowski said. “Everyone wanted an engine and to go faster.”

But the Turner design, he said, ended up extending the life of Equator in the South Pacific. The larger steamships of the day required coal rather than sails to make them profitable, so they were unable to reach places like Hawai’i and Samoa, which did not yet have reliable coal supplies. Equator, he said, was able to fill that gap until more refueling ports were established.

Along the way, Equator faced several near-death scrapes with typhoons and groundings but managed to survive as a schooner. Eventually, though, the owners of the Equator realized in the early 1900s that conversion of the vessel to a tugboat configuration would be more economical. Over the years, it was retrofitted with engines powered by steam, oil, gasoline, and finally diesel, working steadily as a research vessel, a cannery tender in Alaska, and a Puget Sound tug, hauling fish and logs up and down the Pacific Coast.

But by the 1950s, the tug’s creeping obsolescence became undeniable. The owner, Puget Sound Tug & Barge, stripped Equator of its engine, decking, and superstructure in 1956 and sank the hull as a breakwater off Everett’s Jetty Island. For most 68-year-old boats, being scuttled and abandoned would mark the endpoint of their existence. For Equator, however, this was just the midpoint of its 135-year journey.

Dreams Deferred

After slowly rotting in the shallows for a decade, Equator began to get noticed again from some Everett-area residents, especially local dentist Eldon Schalka. By 1967, Schalka and the Everett Kiwanis Club gathered enough funds to raise Equator’s hull from the muck.

Over the next few years, Schalka and a group of Everett donors, including Dick Eitel of Fisherman’s Boat Shop, created the nonprofit Equator Foundation with the intention of fully restoring the old tug to its former glory. In 1972, the vessel was placed on the National Register of Historic Places—the first artifact in Snohomish County to receive such an honor.

By the mid-1980s, the foundation estimated that a refurbishing of Equator would take three years and cost $200,000. The hull bounced around different locations for a few years until landing at the 10th Street boat launch, where today’s open-air shed was built in 1990.

Soon after, the vessel ran into logistical problems. “The Port reached out to museums many times in the ’90s, and there was actually a lot of interest,” Jensen said. “But it would have cost too much money to move such a large, heavy vessel that might not survive the journey.”

The Foundation’s efforts then came to a virtual halt in 1992 with the tragic death of Schalka in a plane crash. From that point on, little more was done to the old tug in the shed. By 2017, the boat that refused to go under finally heard its death knell when its stern section, which had been extended during its conversion into a tug, collapsed under its own weight that November. The Port knew something had to be done before the rest of the fragile structure disintegrated, so the removal process began.

So far, the Texas A&M work on the Equator’s remains has been a boon for 19th century marine archaeology. “There are still some beautiful original 30- to 40-foot Douglas fir timbers left,” Bojakowski said. “The keel is over 60 feet long, all made from one piece of wood. To find timber like that today is almost impossible.”

Ironically, some of the wood’s longevity came from its own rust. “There are so many metal bolts in the timbers that the iron corrosion seeped into the wood itself,” he explained. “It actually impregnates the wood and preserves it.”

One of the most unique aspects of Equator is its curved bow. “It had a very sharp, beautiful entry and expanding to its midship,” he said. “You could see that it was not intended as a tugboat. It was specifically designed from the start as a sailing vessel.”

Artistic License

The Equator story has entered uncharted waters now but will likely continue for many more years. The Bojakowskis plan to write some academic articles about their findings, or perhaps collaborate on a book about the ship’s travels.

The collected wood will soon be sent to celebrated Seattle artist John Grade, who will use the material to honor Equator in sculptural form. Grade also created the massive “Wawona” artwork featured prominently at Seattle’s Museum of History and Industry, made of wood from the old three-masted schooner Wawona, which was similarly dismantled in 2009. While the completion date and final artwork to be made from Equator’s timbers is not yet known, Jensen said Grade’s plan is to use as much of the existing recovered keel as possible.

Meanwhile, the Port of Everett is keen on educating visitors about Equator’s less glamorous but still vital contribution to the working waterfront. “I always find it interesting that the history of the Equator is tied back to its first nine or ten years as a schooner, but she really spent most of her life as a humble tug,” said Catherine Soper, the Port’s public affairs manager. “So, as a seaport, we want to make sure that that story is told as well.”

The Port’s plan, Soper said, is to erect some interpretive displays about the history of Equator by the end of the year, featuring historic photos, a timeline, maps of its journeys, and some videos, located inside the atrium of the Port’s Waterfront Center. A 1:48-scale model of the ship, made by Robert Yorczyk and loaned to the Port, will also be on display.

In addition, the old tug may be remembered best by today’s youngest generation as a playground attraction. In August of this year, an outdoor playset was installed by the 10th Street boat launch featuring a plastic ship for kids climb on, bearing the Equator name on its hull.

“Equator has always been a workhorse, whatever she’s doing,” Soper added. “We see her moving on to live her next days as art. That’s her next job.”

>> For more details on aspirations for the Equator’s afterlife, please visit: portofeverett.com.