Keyport, Washington, is a sleepy little town on a small peninsula between Poulsbo and Bremerton in Kitsap County. There’s not a whole lot of fanfare to this unincorporated community of 552 residents.

Keyport, Washington, is a sleepy little town on a small peninsula between Poulsbo and Bremerton in Kitsap County. There’s not a whole lot of fanfare to this unincorporated community of 552 residents.

There’s the Torpedo Down Diner and the Keyport Bible Church, which claims the largest parking lot in town. There’s the Keyport Mercantile, where neighbors gather and notice the sight of an unfamiliar car. Across the street from the Mercantile is a small park with a spinner merry-go-round that might look lonely if not for the few dogs roaming around. There’s a small post office, an automotive shop, a Mexican restaurant and some houses. That’s about it. Yet, behind this seemingly sleepy civilian cloak sits the starting point of our national defense system—Naval Base Kitsap-Bangor, home of Group 9, a strategic deterrence branch of the United States Navy.

If you’ve not heard of Submarine Group 9, you’re not alone. I grew up boating in Puget Sound waters, but I had no idea that these subs played such an important role in the US National Defense system. However, if you’ve done any boating whatsoever in the region, you’ve likely crossed paths of one of these ten Ohio-class Ship Submersible Ballistic Nuclear (SSBN) submarines and not even known it.

We can’t see them. We can’t hear them. Those in the know have said that people will have better luck finding a needle in a haystack than finding a submerged SSBN submarine.

When on patrol, the SSBN submarines provide an incredible strategic deterrent system. They patrol the world’s oceans with one single critical purpose: to deter an enemy nation from making a nuclear attack on the U.S. And they live right here, in our very own backyard.

The Cold War was an arms race, dominated by the constant threat of nuclear war. In the early 1960s, the Soviets unveiled sophisticated ICBMs and other supporting missile defense systems. In response, the U.S. government launched a classified study called STRAT-X, which was basically a classified brainstorm session to come up with alternative missile systems. Of the 125 ideas that developed from STRAT-X, the study endorsed nine. One of these nine ideas called for enormous ballistic submarines carrying missiles.

And with that, the Navy’s missile program was born and the SSBN class of ballistic missile submarines were designed.

The USS George Washington was the world’s first nuclear-powered, ballistic missile carrying submarine. It’s unlimited endurance while submerged combined with its nuclear tipped Polaris missiles changed the shape of international power politics. The USS George Washington could carry up to 16 Polaris missiles that were to be launched while submerged and would remain undetected for several minutes after firing.

In time, the Polaris missiles were replaced by Poseidon missiles, which were then replaced by Trident missiles. Each model upgrade improved range and accuracy of the missiles.

For more than 60 years, the US has used nuclear weapons to deter nuclear war. By demonstrating the ability to retaliate, the enemy is discouraged from attacking, according to the theory of strategic deterrence. If the program is successful, then it’s a system that never has to be used in a real conflict situation.

Based at the Kitsap-Bangor naval station, Submarine Group 9 is a fleet of ten SSBN submarines comprised of two squadrons; 17 and 19. This fleet oversees all ballistic-missile and guided-missile submarines in the Pacific Northwest.

The program began in the mid-1960s with the Polaris Missile Facility Pacific, which in 1974 became the West Coast Trident Submarine base. The Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in Bremerton also plays a key role, as this is the facility where the SSBN submarines receive maintenance and retrofits, so that the subs are always carrying the newest generation of missiles.

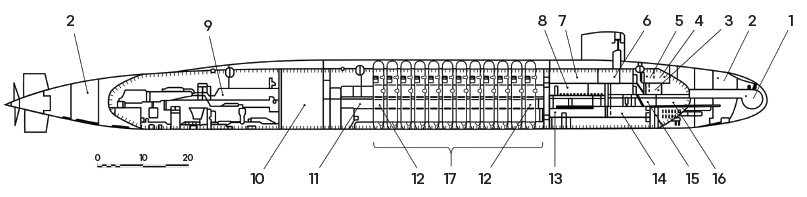

SSBN submarines, powered by nuclear energy, now feature the Trident II D5 Missile Systems. A SSBN sub is 560 feet long (or nearly two football fields) and carries up to 24 missiles. Each one of these missiles carry up to eight 100 kiloton-nuclear warheads.

To put this into perspective, this is about 30 times the explosive force of the Hiroshima bomb, and they are designed to travel more than 4,000 nautical miles to hit their strategic targets.

Due to the stealth operation of the SSBN submarines, recreational boaters in our region might never encounter these subs, despite their routes from the Kitsap-Bangor Base to the Strait of Juan de Fuca and out to the Pacific Ocean. There is a chance if you’re boating near these areas, you may see them surface, complete with a U.S. Coast Guard escort.

Retired engineer Rich Dixson, skipper of a 34’ Mainship trawler Teakless in Seattle, has some stories to tell about his interactions with SSBN subs. On one trip, he was traveling from Poulsbo, Washington, to Pleasant Harbor and was unaware that the SSBN subs were conducting drills in Dabob Bay, on the west side of Toandos Peninsula. He was approached by a U.S. Coast Guard boat and asked to stay clear of the area. His advice to boaters in our region, “Be nice. Follow the rules. Don’t question anything. They will tell you how far they want you to stay away.”

Top Right: Sailors tend mooring lines as the ballistic-missile submarine USS Maine (SSBN 741) at Bangor. (Photo: CS Eric Harrison/U.S. Navy)

Bottom: If you should ever see a Group 9 sub, chances are good it’ll be in a scene like this: under heavy guard. No fewer than six coast guard vessels escorted this sub past Port Townsend.

Typically, the rule of thumb is 1,000 yards of distance between the submarine and the recreational vessel. Dixson reminds boaters that the submarine zones are easily identified on charts and base boundaries are defined with large floating buoys and in some cases, chain-link fencing. “It’s also not uncommon to see them near Bremerton, in Admiralty Inlet, and in the areas around Port Townsend,” he adds.

Dixson has a strong affinity with the Group 9 subs. In 2007, he spent two weeks onboard a sub during a sea trial as a civilian engineer installing software updates. “If you’re claustrophobic, you won’t enjoy submarine life,” he explains. “The only way to tell what time of the day it is, is by what meal is being served,” he adds with a smile. During the return to Bangor, he was given the unique experience to stand on the bridge for 20 minutes after the submarine surfaced.

“There was no noise. No vibration. No smoke,” he describes. “It was totally surreal.”

Civilian tours of the Group 9 subs are very rare, but Dixson, who is a member of the Navy League service organization, has had the opportunity from time to time.

Deployment on the SSBN submarines are typically for two to three months and involve patrol cycles and practice drills in the world’s oceans. Most submariners on board don’t even know their location during their deployment as the sub’s whereabouts oftentimes remain classified even to them.

If you’d like to learn more about the Navy’s undersea operations, technology, combat, research, and salvage, you’ll want to check out the U.S. Naval Undersea Museum located at the entrance to Naval Base Kitsap-Bangor. It’s one of just ten U.S. Navy museums across the country designed to tell the stories of the people and the cutting-edge technology that defines the Navy’s undersea community.

The museum is located on naval base land, but visiting the museum does not require base access. Admission and parking are free. While there, say hello to Rich Dixson, who volunteers both his time and his stories.