Curiosity has nearly killed me twice. My first Indian Ocean crossing was on a Thomas Calvin-designed steel ketch, from Thailand to Turkey in 2001. I was 21, a hitchhiking cook on board. We had two close encounters with pirates (or rather opportunists) while sailing up the Red Sea.

Curiosity has nearly killed me twice. My first Indian Ocean crossing was on a Thomas Calvin-designed steel ketch, from Thailand to Turkey in 2001. I was 21, a hitchhiking cook on board. We had two close encounters with pirates (or rather opportunists) while sailing up the Red Sea.

My first Atlantic crossing was on the wooden trimaran Moxie, built in Maine by Walter Greene for American Phil Weld, who sailed the boat to OSTAR victory in 1980—much to the chagrin of the French! We left Newport, Rhode Island, foolishly in late September, and experienced 12 low-pressure systems in eight days, a record at the time. The last system was Hurricane Kyle, and the night of the 75-knot winds.

Rowing the North Pacific next year will be my 14th ocean crossing and my fourth solo. I will turn 40 years old at sea.

Ten years ago, if you had asked me if I saw ocean rowing in my future, I would have cried with laughter. I breathed to sail the latest and greatest multihulls. My passion was for boats that were like planes, winged leviathans that skimmed the water surface with incredible speed. I liked to fly at 30 knots plus.

In 2008, a Danish Olympic rower invited me to join her in rowing the Atlantic. “Me? Row an ocean? You haven’t even met me!” I said. I was a sailor, not an athlete. I didn’t have muscles for rowing, although on more than one occasion I was forced to row a dinghy when the outboard conked.

The only time I’d been in a gym was in the run-up to a modelling gig in New York in 2006. “Fake running, fake cycling, fake climbing stairs, fake carrying jerry-cans of diesel…” is my summary.

But a seed had been sown. I was curious as to what it was like to spend that much time at sea in a small boat, so close to the water. Later, I did row the Atlantic with a policeman as my partner, from La Gomera in the Canary Islands to Antigua in the Caribbean, in 2010.

I self-funded my part from “danger money” I’d received for delivering a Gunboat 48 catamaran from Cape Town to Abu Dhabi, which took me past the pirate zone near Somalia – something I would never do again. My brother joked that I was rowing with a policeman because I was under the witness protection program (I wasn’t). The policeman and I had only one thing in common: the desire to row the Atlantic. It was barely enough.

I called the Atlantic row my cross-training in preparation for the Barcelona World Race, a non-stop, double-handed, round-the-world race on 60’ monohulls —a race I planned to enter next. I wanted to rig the boat with load sensors and funnel the existing data streams (wind speed, wind angle, angle of heel, rudder angle…) through a synthesizer, so that the boat could conduct its own symphony orchestra. It was a highly ambitious project that saw me spend time with Brian Eno (the forefather of ambient music), Thomas Dolby (who created the polyphonic ring tone for Nokia), and the electronics engineer from Duran Duran.

It was a rare time in that the organizers of the Barcelona World Race were matching sailors with sponsors – Neutrogena with Ryan Breymaier and Boris Herrmann; GAES Centros Auditivos with Dee Caffari and Anna Corbella and the creative side of my entry application meant I didn’t get taken seriously. “Oh Lia,” said Barcelona Race Director Denis Horeau regretfully when we finally met at the start of the 2010 race. I was in Barcelona for the December race start, but working for Alex Thomson Racing/Hugo Boss.

For 10 days, I was Alex’s videographer, working alongside hired French photographer Christophe Launay. A year later, I discovered Christophe was my stalker. Or rather, Christophe and his various personalities were my stalkers.

Hurricane Kyle in 2002 was, at most, a harrowing four-day experience. Being stalked has lasted more than seven years.

In 2011, I disappeared from the sailing world and moved from the United Kingdom to Spain where I quietly wrote a book. Bloomsbury had commissioned me to write the next in their 50 Adventures series. The book 50 Water Adventures To Do Before You Die! is now available in English and German.

I did not have a religious upbringing, but I have always believed in the God of Yachting (the GoY). Need a holiday and can’t afford one? GoY sends me the offer of a transatlantic cruise as a speaker. Need to get off a Spanish island and back into the world of sailing? GoY sends me the offer of a Chris White catamaran delivery from Auckland, New Zealand to Valdivia, Chile.

Once I set foot in South America, I set my sights on rowing the North Pacific, solo and unsupported from Japan to the United States.

Nineteen attempts had been made to row this distance. Two were successful. Both were men, both towed to land for the last 20 and 50 miles respectively. The 17 failures fall under the following headings: challenging departure point, lack of funding, last-minute preparation, late departure, injury, and mindset. Peter Bird was lost at sea in 1996 on his fourth attempt.

Rowing the Atlantic in 2010 had been a real trial, supporting a seasick, homesick person and trying to become a team through those challenges. Rowing the Pacific was going to be about record setting, to be the first woman to row the North Pacific and the first person to row land-to-land.

I can’t tell you how many times I have been asked why I am rowing the Pacific. Nobody seems to buy the idea of me wanting to set a record, although I am sure when Gerard d’Aboville set off in 1991 or Emmanuel Coindre in 2005, their reasoning wasn’t questioned.

Never have I felt more connected to the ocean than on a 21’ rowboat. Whales sonar-ping the hull or surf the same wave, eyeballing me sideways. “Squeak, squeak, squeak!” dolphins swim up to the gunwale a foot from where I sit. “I don’t speak dolphin!” I joke back. Sometimes a dolphin pod swims around the boat for hours, keeping me company like a dog at your feet.

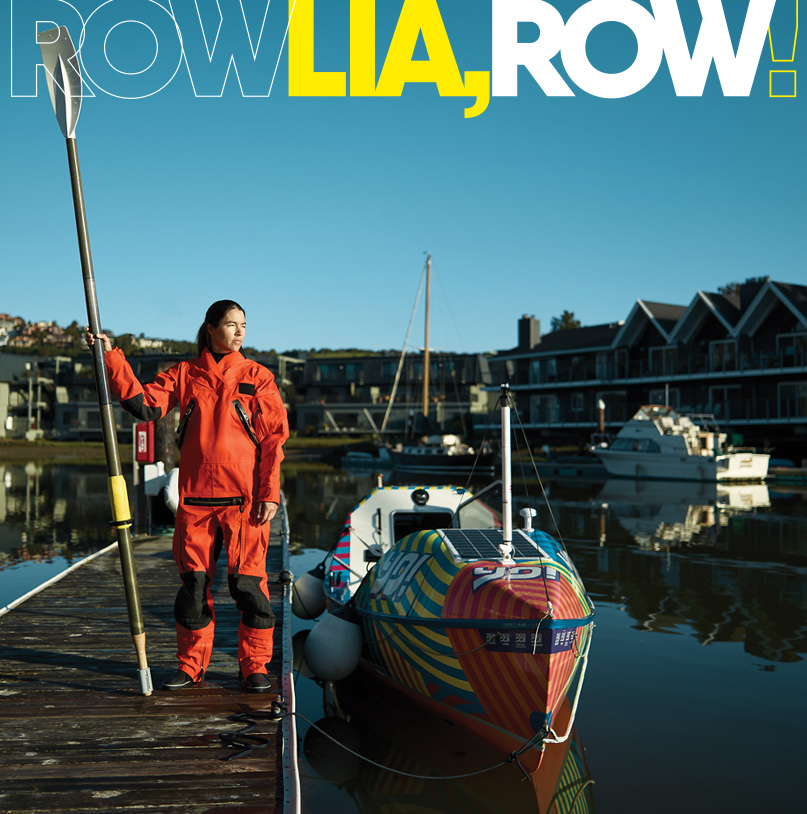

In the spring of 2016, I bought my current rowboat. I bought a survivor, a boat that washed up in Ireland after spending three months alone at sea after its owner stepped safely onto a passing ship. The boat needed much repair, but I was fortunate to secure a sponsor who paid for the repairs.

I shipped the boat to San Francisco. A perfect training ground, I thought, as the San Francisco Bay is like an ocean in a bowl. I became a well-known sight out on the Bay. Ferry captains would hang out of the window and wave. The tourist boats from Alcatraz to the Golden Gate would divert and their passengers would stare down on me. Commercial ships would see my AIS transmission and out of curiosity, turn on their apocalyptic search beams to find me in the dark. (I can’t tell you how terrifying that is!)

My attempts to row out to and around the Farallon Islands – 26 miles west of San Francisco – became news in the San Francisco Chronicle newspaper. On record, no one had rowed to or from the Farallon Islands since 1892 and the era of the lighthouse keeper.

My first and second attempts served unexpected blows of humiliation and defeat.

Waiting for me at the dock after the first attempt was a mother and two young girls. They had been following my tracker. “Not today,” I thought. “Please no.” The mother gave one of the girls a nudge. I had barely tied up the boat.

The little girl looked up at me standing in front of my ocean rowboat, as if I were magical, as if I were a Disney princess. She handed me a note on pink paper and my eyes glistened. “I admire you for trying,” I read the note. “You will do it next time.”

The note reminded me of when I was 10 years old. Our town was sponsoring sailor Josh Hall in the solo BOC round-the-world race. His boat Spirit of Ipswich was in front of the town hall on a cradle, and our school bussed us there to draw his boat. I won the drawing competition. Even now I can remember the thrill of climbing the ladder to his boat, meeting Josh, wearing my prize (t-shirt) until it wore out and listening to the cassette tape of Josh sailing under full power. Until then, I didn’t know that sailing around the world was an option. Meeting Josh and his boat threw open the doors of possibility.

I wondered if that day I did the same for the little girl with the pink note.

For two years, I told the world that I couldn’t row the Pacific until I had a new boat that could withstand a typhoon. Finally, I commissioned Jim Antrim to design a potentially lighter faster boat. But was my delay really about the boat? In part, I think it was. In part, I think it wasn’t.

I couldn’t have foreseen that in training my body to row the Pacific, I would find the mental strength to face my biggest fear. Not typhoons, sharks, or waves the size of buildings. Not rowing 5,500 miles across an ocean. In February, this year I spoke out for the first time about being stalked and publicly named Christophe Launay as my stalker. Speaking out was the boldest, scariest thing I have ever done.

By the time this article comes to print, we will have finished the refit at Betts Boats in Anacortes, Washington. I weighed up the advantages of rowing the boat I have, in which I have now rowed 2,067 miles and experienced two storms, versus a new boat in which I have zero experience. I made the decision to row across the Pacific in the Phil Morrison-designed boat that I already own, but make it typhoon proof.

Thanks to boatyard owner Jim Betts, my boat is now 100 pounds lighter with carbon roll-over bars across the cockpit, carbon cabin faces with custom carbon hatches, and a main cabin with better ergonomics and reconfigured for my 5’ 8” height.

The continuation of the project is thanks to a special family of people I call my “Believers” who pledge between $1 to $250 per month via patreon.com/rowliarow. In return, I offer a backstage pass to the project with special updates and access to a private Facebook group where I share behind-the-scenes content.

I’m hoping to fund the costs of the row with my Slice of History campaign. After I row the Pacific, my boat will be cut into 60 three-inch thick ring frames or wall sculptures. Each Slice of History will go on to have a new life, adorning the walls of homes, offices and schools, to tell the story not of how Lia Ditton became the first woman to row the North Pacific, but of what the mission came to represent: resilience through adversity, determination against all odds, and dogged unwavering perseverance.

When you buy a slice, you receive a Certificate of Slice Ownership /Willy Wonka-like ticket to the Slice Exhibition private viewing, where the slices will be hung from the ceiling like the vertebrae of a dinosaur in the Natural History Museum.

Each Willy Wonka ticket is a beautifully engraved 9” wooden chopping board, and my joke at presentations is that in the worst case scenario, where I have to be rescued and my boat abandoned and unavailable to be sliced, you have a chopping board! At $3,500 for individuals; $5,000 for corporations, twelve out of 60 have sold.

To add even more art to the equation, Wes Archer, one of the original animators for the Simpsons, has designed the new vinyl wrap for my boat. My struggle will become art with the beautiful vertebrae of my boat set to inspire generations.

In December, I will depart the Pacific Northwest for Japan to prepare for the expedition of my life. Think of my row as the super-slow Olympics as I will leave before the Tokyo 2020 Olympics and chances are, I will still be rowing after the Olympics. The plan is to reach the same shores in San Francisco Bay where the little girl gave me her pink note.