We’ve all heard stories and seen pictures of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP), a massive floating island of trash and plastic hovering just northeast of the Hawaiian Islands. Many of us have seen plastic jugs, soda bottles, and grocery bags bobbing on the surface of Puget Sound as we make our way from port to port.

We’ve all heard stories and seen pictures of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP), a massive floating island of trash and plastic hovering just northeast of the Hawaiian Islands. Many of us have seen plastic jugs, soda bottles, and grocery bags bobbing on the surface of Puget Sound as we make our way from port to port.

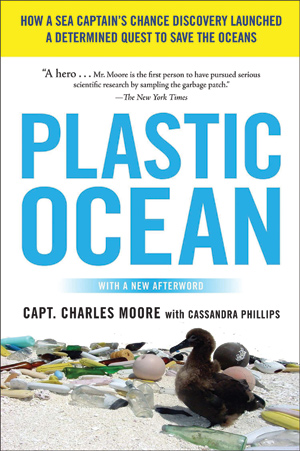

In Plastic Ocean, Captain Charles Moore tells his own story of discovering, documenting, and fighting plastic pollution in our water and on our shores. It is a book of science and conservation to be sure, but it is also a moving series of stories about Captain Moore’s adventures at sea. It is through his love for sailing and the ocean that he found himself immersed in hands-on research into the true sources of plastic pollution. The book is full of surprises beyond the sheer scope of plastic pollution in the oceans. The first surprise: Moore and his colleagues have been actively studying the GPGP since the late 1990s. Why has this massive, 617,763-square-mile floating dump just recently become news? It turns out that part of the problem was figuring out how to study it and how to measure it.

The GPGP sits in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre, where the wind seldom blows and where tourists and casual sailors seldom venture. Moore happened upon it on a return trip from the Transpac Race in 1997 and has been studying it on some level ever since.

Don’t worry that this book will be a preachy environmentalist’s creed. Moore objectively traces the history of plastic development and its introduction into the consumer mainstream. He lays little blame on a single source, but he definitely sounds the alarm. He makes the case that plastic is killing our oceans and doing as much or more damage than the warming of the water and the increased acidity of our oceans. We no longer live in a country where urban rivers catch fire, thank goodness, and bodies of water like Lake Washington, which used to be too toxic to swim in, have been cleaned up and managed quite well despite the increasing population pressure at their shores. But plastic is pouring into the sea faster than anyone can measure.

Forget the dramatic scenes of whales and seabirds dying on the shoreline with bottle caps and pacifiers in their stomachs. Yes, much of what is floating out there in the Pacific is post-consumer waste, but that is easy to see and therefore relatively easy to clean up. The more nefarious danger comes from microplastics, most of which are in the atmosphere and in our waterways as a result of the manufacturing and shipping of plastic to the factories that make the doodads we buy every day.

It is little surprise to learn that one of the biggest contributors to the GPGP is the fishing industry. When trawlers went from wooden and glass floats to plastic and foam buoys, and nets changed from hemp to monofilament, things changed. A lost or cast-off fishing net keeps fishing. It catches fish and birds, to be sure, but it also catches other garbage. Perhaps worst of all, it “catches” sea life like barnacles and mussels, which hitch a ride to wherever the ocean currents decide to push it. This introduces non-native and invasive species to any ecosystem in the current’s path.

We can’t go back in time. We can’t go back to World War II and stop the development of petroleum-based materials. We can’t stop DuPont and the rest from delivering plastics to the consumer in the post-war rebranding of military materials. But what Moore thinks we can do is declare “peak plastic.” From here forward, we know too much to allow the oceans to continue to be polluted at such a rate. And, while the greatest polluters are large corporations, shipping companies, cruise lines, and the military (the U.S. Navy has a terrible track record of dumping trash in international waters, for example), that all changes if the consumer drives the change.

According to Moore, “a consumer groundswell against plastics is the most potent weapon in the change agent’s arsenal.” If we stop buying plastics at such an alarming rate, less will be produced.

In the face of such daunting, worldwide problems it is hard to imagine that what one of us does on their boat matters all that much, but it does. After reading this book, we began to rethink our provisioning and refuse practices onboard. We carry fewer packaged foods. What we do buy in plastic packaging we unpack at home before loading it onboard. This allows us to make use of land-based recycling centers and reduces the chances of a plastic clamshell box accidentally ending up floating away in our wake. When we see something floating in the water, we deploy the fishing net and bring it to shore with us. These things all help.

Plastic Ocean is one of the better books I’ve read this summer. It reads like an adventure tale and never preaches. It offers astonishing facts and figures but doesn’t rely on them to tell the story or to shock us into action. Story sticks with us. I don’t remember all the facts and figures from this book, but I remember Moore’s story. I think you will too.