ship met its end on Willapa Bay

Fifty years ago, the 125′ long by 30’ wide expedition ship Hero was taking shape at the Harvey Gamage Boatyard in Maine. Designed by Boston, Mass. naval architects Potter & McArthur, Inc. and based on a traditional fishing trawler, it was the last wooden vessel built in the U.S. for polar service—specifically to supply the Palmer Station in Antarctica. By 1984, the 300-ton vessel was worn out by 17 grueling voyages south and was also completely outdated. It was decommissioned and put up for auction.

Fifty years ago, the 125′ long by 30’ wide expedition ship Hero was taking shape at the Harvey Gamage Boatyard in Maine. Designed by Boston, Mass. naval architects Potter & McArthur, Inc. and based on a traditional fishing trawler, it was the last wooden vessel built in the U.S. for polar service—specifically to supply the Palmer Station in Antarctica. By 1984, the 300-ton vessel was worn out by 17 grueling voyages south and was also completely outdated. It was decommissioned and put up for auction.

The Hero‘s survival depended on the next owner. At a minimum, it needed to be someone with a knowledge of wooden boats and a solid business plan—or a million dollars to spend. Unfortunately, the only bidder was a group of dreamers in Reedsport, on the mid-Oregon coast, who picked it up for just $5,000.

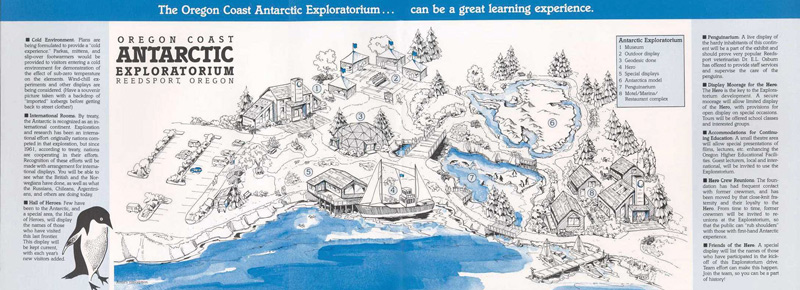

This heroic little ship’s fate was to become the static centerpiece in the incredibly over-ambitious plan to build an “Antarctic Exploratorium.” These local boosters even tried to bring in the powerful 309′ diesel-electric icebreaker Glacier, launched in 1954 and mothballed in the San Francisco Bay area since 1986. Other attractions would have included Antarctic aircraft and vehicles, a conference center, penguin pool, etc.

The state grants the Hero Foundation obtained were all spent on consultants and architects while the Hero sat at the dock in the Oregon rain and did what all wooden boats do—rot. After a decade, the money and enthusiasm ran out, and in 1998, the boat was sold for a song. The “lucky” owner was an experienced seaman who managed to keep the ship afloat and operational in Newport for the next 10 years. I remember finding Hero at the fish dock and wondering how on earth it had arrived there during this time.

He tried various strategies like short cruises and a bed and breakfast, but a vessel of this size runs up a sizable bill just sitting at the dock. About 24 years after its last expedition, the Hero changed hands for the last time and was towed to its final home on a private dock in Bay Center on Willapa Bay on the south Washington coast. It might have been better for all concerned if it had sunk offshore—a common occurrence—but it arrived safely and sat at its berth on the Palix River for the next nine years.

The new owner was a man with native American heritage named Sun Feather Lightdancer. He too appeared to be another dreamer with no clear plan or funding. By 2012, he was reported to have removed all the marketable items from the bridge while seemingly unaware of the risk that he was taking by keeping the now-derelict boat smack in the middle of the biggest oyster-growing area on the West Coast. Needless to say, the oyster growers were not impressed by the new arrival and viewed it with suspicion from the start.

“Oyster boats passed it every day on their way to the Goose Point plant nearby. Their remote setting facility is just downstream and they have a significant number of beds in the Bay Center area,” Brian Kingzett, senior biologist of the Goose Point Shellfish Farm and Oystery, told me. Having the boat sink at dock was their worst fear realized. All the growers’ protests went unheeded until 2015, when they convinced the authorities to inspect the boat’s hold and a small quantity of oil was removed. But no further action could be taken.

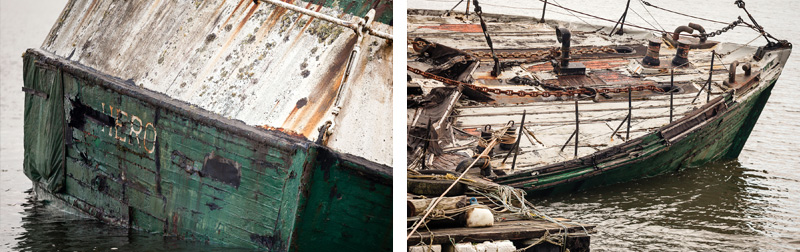

Unfortunately, the threat of pollution isn’t enough of a legal cause for the U.S. Coast Guard to act, and the Hero was not even added to the state program’s list of “Vessels of Concern” in 2015 because there was no sign of an oil sheen. But this slow-motion disaster inexorably reached its conclusion in March 2017, when the Hero slipped below the muddy water of the Palix River, ending its career “not with a bang, but a whimper.”

The U.S. Coast Guard opened the Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund for $25,000 to minimize pollution potential, and the Washington Department of Ecology (Ecology) immediately sprang into action. Ecology contracted with Global Diving & Salvage of Seattle to clean up the spill. Workers recovered more than 1,000 gallons of oily water and 60 to 70 gallons of diesel fuel and oil. The oyster beds managed to avoid a more serious shutdown.

But a closer look at the hull at low tide revealed an unexpected aspect of the problem: the heavy hull was in a very fragile state and would probably not withstand the strain of being re-floated and temporarily patched. The float-and-patch method would have enabled a tug to tow it slowly to nearby Raymond, Washington, where it could be hauled out or cut up on a ramp. As it stands today, the Hero is too far from the shore, too heavy, and too far gone for a mobile crane to lift it out.

Harvey Gamage Shipyard:

Established 1924

From 1924 to 1976, Harvey Gamage personally oversaw the construction of more than 288 vessels—sailboats, powerboats, draggers, scallopers, and windjammers, as well as schooners designed by the well-known naval architect John Alden. Powerboats and small fishing and lobster boats became more common in the 1930s and 1940s. The construction of eight wooden military vessels occupied the Gamage yard from 1940 to 1944.

In 1944, the business turned to building rugged, able, and profitable wooden fishing boats. A total of 93 boats were launched between 1944 and 1969, averaging about four boats a year. These heavily-framed, diesel-powered boats ranged from 70’ to 112’ in length, and formed the backbone of the Gloucester and New Bedford, Massachusetts, fishing fleets.

In 1959, Captain Havilah Hawkins asked Gamage to build the first schooner designed specifically for the windjammer passenger trade. The result was the 83-foot Mary Day, launched in 1960. From that date until 1976, when Harvey died, the shipyard’s output was 43 vessels—a mixture of draggers, research vessels, yachts, and large schooners.

In addition to the schooners, the Clearwater slid down the Gamage ways immediately after Hero. This sloop was a historic replica modeled after the Dutch vessels that sailed the Hudson River in the 18th and 19th centuries. It became the flagship for the restoration of the Hudson River with the support of folk singer Pete Seeger.

As a reminder of the long-term costs of maintaining a big wooden vessel, the Clearwater (seen below) underwent a complete structural restoration recently that cost close to $1 million. These traditional designs were followed in 1970 by the yard’s first steel-hulled fishing vessel—another sign that the Hero was really the end of the line for Maine’s long history of commercial wooden vessels.

In any case, there is no money available to clean up the wreck, so it could be around for a considerable time. This sad situation joins a depressing list of derelict sinkings in the Pacific Northwest, all of which could have been avoided by government intervention before it was too late. However, this is not the way the law works. Troy Wood, derelict vessel removal program manager for the state Department of Natural Resources, explained this quandary very succinctly: “It was reported to us that it was ugly-looking, but it’s not against the law to be ugly,” he said.

Ironically, this entire dismal saga has been regularly followed by a group of Palmer Station veterans who have annual meetings and an online newsletter. It’s easy to understand the sadness and regret they feel at their failure to bring the boat back to Maine, where there is a fleet of wooden charter schooners and several traditional yards capable of maintaining them. The old Hero might have enjoyed a new lease on life and even earned its keep carrying passengers around Penobscot Bay. The Antarctic icebreaker Glacier also had a strong support from former crew and efforts to save it continued into 2012 even as it was towed to the breakers’ yard in Brownsville, Texas.

He reckoned the boat now has almost 2,000 nautical miles under her keel in her third incarnation. “This boat was built for 20-year-olds. It’s hard on you physically and I’m now 75,” he admitted. I noticed how it now had the name Point Adams. That is because you need a name, not just a number, for a boat in Washington. “We chose that name to honor the boat’s service to the Point Adams station in Hammond.” Glen and Naomi have brought the boat back home to Goldendale after a thwarted attempt to appear at the Port Townsend Wooden Boat Festival. They are now settling in for the fall.

The Hero’s original ship’s specification has been preserved by the Palmer Station club, and states “six scientists and a crew of 12 comprise the normal complement which for special cruises may be increased by seven transient personnel. Designed primarily for trawling and other biological collecting. Hero has three laboratories to support diverse research activities.” The backbone consists of an 18” x 18” keel and 6” x 6” framing spaced only 8” apart. Oak planking 2” thick covered the frames, and the sheathing along the forward part of the hull was tropical greenheart from Guyana overlaid with steel sheets.”

The ship was designed with a draft of 14’ to reach previously inaccessible areas, and to operate alone in close proximity to sea ice.” It made the first surveys of many islands and inlets in a time when the sextant was still the primary instrument of navigation. The masts and booms were Oregon fir, and the ketch rig, with about 1,700 square feet of sail, was often used to steady the motion and allowed the crew to do some sampling and research in silence. The sailing rig also acted as a back-up to the engines.

The twin 368-hp main diesel engines drove a single propeller shaft, giving a cruising speed of 10 knots, while a massive 75 tons (2,400 gallons) of fuel allowed a range of up to 6,000 miles. With redundant double boilers and circulating pumps for standby heating, two gen-sets, plus a spare shaft and propeller, it was well prepared for all the hazards it might encounter.

The superstructure consisted of a pilothouse with small bridge, navigation/radio room, and a small aft deck on which the hydrographic winch with 12,000 feet of 3/16” wire and two nested dories were located. The captain’s cabin and berths for three crew members were below on the main deck adjoining a dissection laboratory and a large freezer for the storage of biological collections. The main deck was enclosed at the bow to accommodate the hydrographic laboratory, located on the port side, and storage areas. Amidships was an electric deep-sea trawling winch with three drums holding over 20,000′ of ½”-diameter wire.

The lower deck accommodations from bow to stern included cabins for eight crewmen, a mess, a galley, three two-man cabins for scientists, a large hold for storage of equipment and supplies in which bunks for as many as ten persons could be accommodated, a microbiology laboratory, the engine room, and spaces for three crew members. Fuel and water tanks were in the bilge below this deck. I have no doubt that today’s marine scientists would be appalled by the tiny living quarters crammed into odd spots all over the boat.

Throughout the 1970s, the boat continued ferrying geologists, biologists, and other scientists to Palmer Station during the short Antarctic summer. In 1972, the crew helped Jacques Cousteau and the Calypso when a member of his crew was fatally injured in a helicopter incident. The boat also came to the rescue of Polish scientists when their research station ran dangerously low on supplies, and, in 1984, helped scientists at the Argentine research station after their base burned down.

The decommissioning of the Hero was the end of an era in many ways. Its successor was the steel research vessel Polar Duke, a 219’, ice-strengthened ship with an A-frame crane on the stern and a helicopter deck on the bow. After 12 years of service, it too was replaced as the march of progress quickly overtook it with a succession of new designs. Today, cruise ships loaded with tourists visit polar areas that were first charted by the Hero—a little ship that truly lived up to its name.