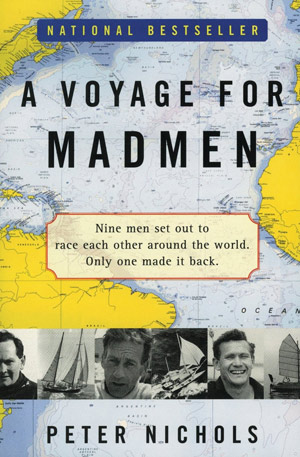

A Voyage for Madmen by Peter Nichols

The most amazing nautical adventure story in modern history isn’t Slocum circumnavigating the globe in the late 1800s, it isn’t a solo sailor surviving against all odds after being dismasted in the Pacific, and it isn’t a shipwreck survivor fighting her way back to civilization. The most incredible nautical adventure still is that of Donald Crowhurst in the inaugural Golden Globe Race. His story is so epic and tragic that even today it seems too scripted to be true, fitting for the story of a man who faked his way around the globe using sophisticated cartography and electronic trickery.

You likely already know the basic story of Crowhurst’s ill-fated entry into the first Golden Globe, and you will be hearing more about it in the coming year as a movie project based on Crowhurst’s story hits the theaters. When I heard of this cinematic competition for what I’ve always considered the greatest adventure story in history, I decided it was time to revisit Peter Nichols’ fabulous story of that ill-fated race.

In 1968, nine sailors set out to be the fastest around the world, single-handed. The feat had been accomplished before by at least 18 people, including Joshua Slocum, who was the first to do so. But never had it been done nonstop. No provisioning. No repairs. The rules for the Golden Globe were shockingly simple, and entry was mostly a matter of putting up a boat and declaring oneself a competitor.

Donald Crowhurst came to the race as a talented but eccentric electrical engineer. He had an inventor’s mind and the crushing debt that went along with all of his failed creations. Unlike the other entries in the race, including Sir Robin Knox-Johnston and Bernard Moitessier, Crowhurst had almost no sailing experience, and certainly no open water miles to speak of.

Crowhurst also had no boat. He had no sponsors.

But he saw the race as a very public way to advertise his business and his inventions. Peter Nichols takes us through the preparations, and we wince with the confidence of hindsight at every shortcut and risk Crowhurst takes along the way. The boat he finally has built is called Teignmouth Electron, a 40’ trimaran made of plywood. Pictures of him standing on deck, barely 12’ of freeboard showing, make it look as if the boat was sinking before the race even started. You and I would certainly not readily head to sea on such a boat.

Sailing around the world solo on a modern boat with redundant safety features and a suite of electronics is daunting enough. Crowhurst leaves port on the last possible day to still qualify for the race, his boat still unfinished, and his electronic systems not properly functioning. We all know the outcome. He didn’t make it. Crowhurst’s boat was found adrift in the Atlantic Ocean. This isn’t a spoiler. We know going in that he doesn’t return to England.

Sailing around the world solo on a modern boat with redundant safety features and a suite of electronics is daunting enough. Crowhurst leaves port on the last possible day to still qualify for the race, his boat still unfinished, and his electronic systems not properly functioning. We all know the outcome. He didn’t make it. Crowhurst’s boat was found adrift in the Atlantic Ocean. This isn’t a spoiler. We know going in that he doesn’t return to England.

The ending isn’t the story. The story is in what Donald Crowhurst did accomplish. In addition to sailing a leaking, ill-fitted boat thousands of miles into the deep South Atlantic, Crowhurst made the world think he was somewhere he was not. He faked his way around the globe.

Using his extensive knowledge of radio communications and chart plotting, Crowhurst managed to remain unseen on the ocean while sending messages back to the mainland that made it seem as if he were making incredible progress. At one point, he claims a 24-hour distance record, while in reality he was drifting off the coast of South America. He kept two logbooks, one of his actual positions so he knew where he really was, and one of his fake positions, which ostensibly he would hand over to the race committee at the finish as proof of his voyage. The details of his deceit and the actual voyage he makes are painstakingly researched and detailed by Nichols, and this book reads like fiction.

Unlike other books about this same race such as The Strange Last Voyage of Donald Crowhurst, Nichols’ book covers all nine sailors with incredible detail and care. Still, it is Crowhurst’s tragic tale that sticks with you. You want to treat him like a con artist or a thief. You don’t want like him, but you almost have to. You can see his downfall coming as tiny pinpricks of bad decisions begin to add up and you beg him to not go. As a sailor, I am more amazed at what he accomplished with so little experience and such a hopeless vessel under him than I am bothered by his dishonesty. I wonder, as I finish the book for perhaps the third time, what would have become of Donald Crowhurst had he survived. What he did was dishonest. It was deliberate cheating. But the scope of his accomplishment is staggering.

In the coming months, when Colin Firth hits the screen as Crowhurst in the film now titled The Mercy, we will get to see the cinematic retelling of this story, but as with all adaptations of real life stories, much will be lost to the confines of the cinematic experience. Take the time to read Nichols’ account of the race before heading to the cinema.