Looking towards retirement, Dr. Jim Gallarda envisioned sailing towards the horizon once he tied up his distinguished career as a research scientist focused on infectious diseases. After years of traveling the world, going to disease hotspots, and grappling with epidemics, Dr. Gallarda was ready to respond to the call from the sea.

Looking towards retirement, Dr. Jim Gallarda envisioned sailing towards the horizon once he tied up his distinguished career as a research scientist focused on infectious diseases. After years of traveling the world, going to disease hotspots, and grappling with epidemics, Dr. Gallarda was ready to respond to the call from the sea.

“How could you not want to be out on the water?” he asks, looking out onto the view of sailboats and cruise ships from his home in the Magnolia neighborhood of Seattle.

The Salish Sea and a job as a Gates Foundation program director brought the Gallarda family to the area six years ago. He had dabbled in sailing when they lived in Illinois and Massachusetts, but it was when he and his wife, Bobbie, moved to Seattle that he became serious about sailing.

All he needed was a boat. Not any boat. The right boat. In between his travel and work commitments, he scoured the Pacific Northwest for his sailboat. It took years to find her. Once he thought he found the right boat up in Vancouver, British Columbia, but it turned out to be a false promise. He decided it had to be a wooden boat, because “I am a bit of a romantic.”

Then one day on Lake Union, he spied the Dulcinea, a 28-foot ketch. Her lines were elegant, sleek, and simple. Best of all, she was for sale. “Once you see it, the lines are so beautiful. They are sheerlines, like sheer beauty. You’ve heard of love-struck—well, I was boatstruck.” He started talking to the owner and found out not only was it a beautiful boat, but the Dulcinea is also a Rozinante, an iconic model designed by L. Francis Herreshoff.

Herreshoff was an eccentric curmudgeon based in Marblehead, Massachusetts, who designed more the 75 sailboats before he died in 1972 at the age of 82. Most of his sailboat designs were long, narrow, and fast, and they were known for “sheer” beauty. He focused on wooden boats, as Herreshoff considered fiberglass to be “frozen snot.”

He was not a fan of modern, fancy yachts either. He said, “A beautiful sailboat is ageless, she will still be in style long after the abortions of the present are forgotten, for every curve of her shape is for some specific reason and not some crazy whim of her designer to create a ridiculous controversy.”

While he was recognized as a genius among the East Coast sailing set, he was eccentric enough not to gain wide commercial appeal. However, his reputation grew through the years and there is a quite a cult built around the man some consider a patron saint of American yacht design.

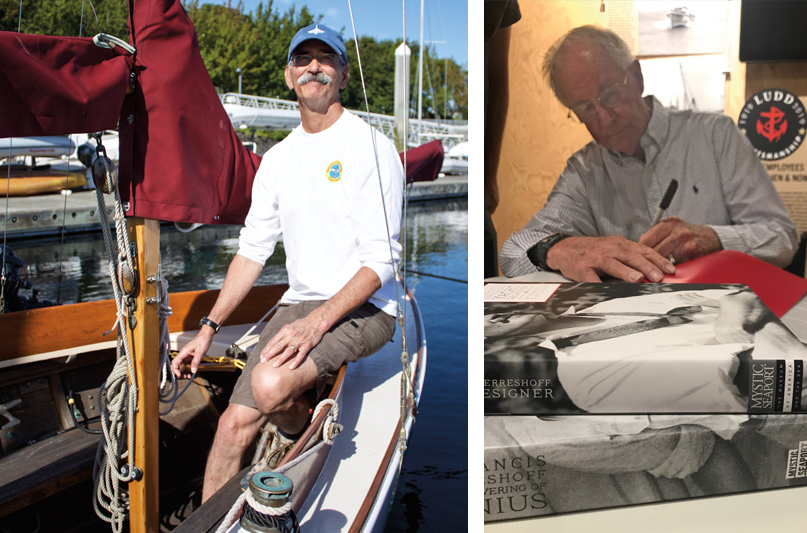

Above: The Dulcinea catches the eye as it rests in its berth at Elliott Bay Marina. The Rozinante’s elegant lines stand out among the many boats in the marina. Attractive lines are an attribute of a Herreshoff-designed boat.

This past summer, there was a gathering of Herreshoff’s local following at the Center for Wooden Boats (CWB) on the shore of South Lake Union in Seattle. They came to hear Herreshoff biographer Robert C. Taylor, who has published two massive volumes on the man.

Taylor is to Herreshoff what author Robert Caro is to President Lyndon B. Johnson; both authors are experts and have written volumes on their famous subjects.

Taylor first became enamored of Herreshoff’s work when he was just 11 years old and an avid reader of Rudder Magazine for Yachtsmen, in which Herreshoff contributed stories and build-your-own-boat designs. The magazine was published from 1891 until June of 1977.

Taylor would eagerly await each issue, wondering what Herreshoff would reveal in that issue. When Taylor was in prep school, he and a friend went to Marblehead and knocked on the door of The Castle, Herreshoff’s home that was made from stone, complete with turrets and a view of the harbor.

“We just had to sit at his feet. If you wanted to know anything about boats, he was the man to go to. He was a guru of boat design,” Taylor said. It was bold of Taylor and his friend just to knock on the door, however, the man did not believe in phones.

He was a character, Taylor admits.

The two became lifelong friends and now, Taylor is maintaining Herreshoff’s legacy. One of the driving forces in Herreshoff’s life was to measure up to his father Nathanael’s work. Taylor said the son was inspired by his father but never copied his work.

A famous sailboat architect, Nathanael Herreshoff’s ship designs dominated the America’s Cup for almost three decades, while son L. Francis Herreshoff never won the sought-after trophy.

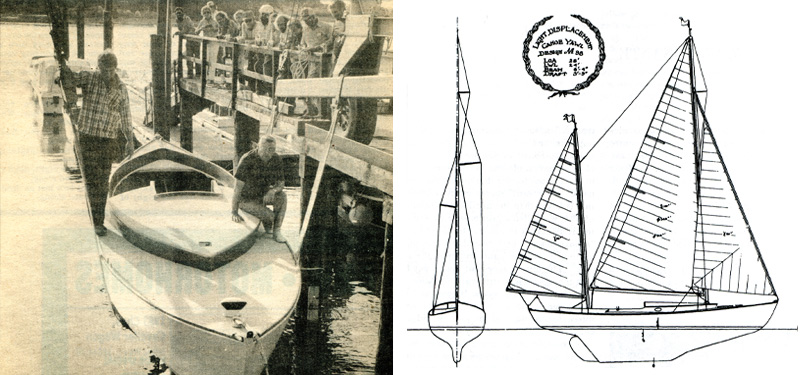

After failing to snag at least one America’s Cup, the younger Herreshoff turned to designing cruising yachts, such as the 72-foot oceangoing yacht Ticondoroga, and writing articles and DIY boat plans for Rudder. The Rozinante was one of these plans and Herreshoff designed the 28-foot yawl for daysailing and light cruising. It was the most popular design the magazine ever published.

The model exemplified Herreshoff’s philosophy perfectly. In the book Sensible Cruising Designs, there is printed a conversation between Herreshoff and the Rudder editor. It’s like watching one of those old black and white movies where the dialogue is fast and witty:

“Do you think yachts and boats used to be more sensible?” asks the editor.

“Yes, I do,” Herreshoff answers. “In years gone by, most boats, from the fisherman’s dory to the square-rigged steam yacht, had character, grace, and perfection.”

He also says in the same piece that if a regular guy wants to sail, boats need to be more affordable. Not one to shy away from expressing his opinion, Herreshoff says “…under present conditions about all he can be is some sort of a gigolo yacht jockey if he wants to go sailing.” Mind you, this was back in 1942. Imagine what he would say if he saw the luxury yachts of today.

Taylor has sailed 14 boats of Herreshoff’s design and he says the Rozinante is his favorite. “It’s a wonderful little boat. A boat you can take in rough water. A long, narrow boat that can take the seas with speed,” Taylor said in his talk at the CWB.

Of course, Dr. Gallarda was in the audience that night and when he heard Taylor praise the Rozinante, he beamed with pride. He knew from the moment he saw her that Dulcinea was special.

Being a researcher, he investigated her past. He went home and checked his library, finding Sensible Cruising Designs, a compilation of Herreshoff’s work in Rudder, already in his collection. Discovering he already possessed a work of Herreshoff was a sign that he and Dulcinea were meant to be.

He told his wife and first mate Bobbie that he finally had found “The One.” She wasn’t wild about the idea. “I was at the point of our lives where I wanted to simplify,” she says and shrugs her shoulders. “It makes him happy,” Bobbie replied when asked how she is enjoying the Wooden Boat Festival.

Dr. Gallarda started digging up more about Rozinante design. The first mention of the Rozinante was in The Compleat Cruiser, a fictional book written by Herreshoff. The book was a way for Herreschoff to express his opinions about boating—it should be simple and delightful, economical, and easy.

Inspired by the story of the man with the impossible dream, Herreshoff named the design Rozinante, after Don Quixote’s steed. In the book, the dinghy behind the sailboat was Sancho Panza. When Gallarda read the Compleat Cruiser, he saw the humor in his own situation.

“I’m the crazy old man, Don Quixote, chasing after the impossible, only my windmills are wooden boats.” Dulcinea is the name of Don Quixote’s love in Cervantes’ novel and Gallarda also found that fitting since sailing is his new passion.

The sailboat Dulcinea has her own fascinating story. She was built in 1983 on Lopez Island by Hank Chamberlin for Fred (Ted) Kennedy. Kennedy had wanted a Rozinante since he first read about her design in the Rudder years ago.

He was so intrigued by the clean lines and aesthetic beauty of the design that, as a youth, he built a model of her, according to a news clipping from The Journal of the San Juan Islands. Chamberlin was a second generation boatbuilder and the craftsmanship shines in Dulcinea today.

Originally christened Intrepid by Kennedy, the boat was given the name Dulcinea by her second owner, Darryl Carver.

When Carver showed the boat at the Lake Union Wood Boat Festival, he described her as: “Delightful to sail, she is quiet, responsive and forgiving, yet has clocked 7.5 knots by GPS on a broad reach in 15 knots of wind.”

When Carver sold the boat to Dr. Gallarda two years ago, the new boat owner knew structural work had to be done on the boat. What doesn’t need work after 30 plus years? He took it to the Shipwrights Co-op in Port Townsend. There shipwright Paul Rust plied his craft and restored the vessel.

Dr. Gallarda decided he wanted to do the rigging himself and he took a class from Brion Toss, a world-renowned rigger in Port Townsend. He would go to Port Townsend to work on the boat when he had a weekend free.

Working on the boat 14 hours a day was relaxing for Dr. Gallarda. One day when he was struggling with the rigging, a gentleman came up to him and said, “I think my brother built that boat.” It turned out to be Hank Chamberlain’s brother, who told Dr. Gallarda that, unfortunately, his brother had passed away a couple of years ago.

At the beginning of this year, Dr. Gallarda retired from the Gates Foundation. Now, he goes down to the Elliott Bay Marina almost daily to sail or work on the boat. He does have a mighty sweet workshop in his garage where he can build items for the boat.

The latest project is re-doing the cabin below deck. He ripped out the sparse interior and now is building two berths and a tiny galley for below deck. Even with the remodeled cabin, the boat is still spartan.

One of Herreshoff’s idiosyncratic beliefs was that boating should not be a luxury sport. In Sensible Cruising Designs, he states, “There will be many who will want more head room than Rozinante’s proportions would allow, and to them, I will say that most of the sailormen I have known sat down where they ate, and much preferred to lie down when they slept. …if you like eating better than sailing, you should stay home and have a barbecue in the backyard. Then you can turn in and sleep off your gastronomical jag.”

Herreshoff had no problem transforming his strident opinions into boat design. The action was on the deck, so down below should not be cozy or comforting. He promoted the use of a bucket and cedar chips, rather than putting in a proper head. There was no time or need for such a thing if you were truly into the moment of sailing.

Dr. Gallarda finds Herreshoff’s quirks charming, which is a good thing since he is 6’2’’ and has to duck every time he goes into the cabin. Cramped quarters was a none too subtle attempt to get sailors out in the elements. However, Gallarda did drawn the line at the bucket with the cedar chips. The new cabin will have a more suitable head.

Herreshoff mostly designed these boats for wandering about the local inlets and bays of New England. This aligns exactly with Dr. Gallarda’s intent for the Dulcinea. He and Bobbie hope to tour the inlets and tucked-away marinas of the Salish Sea. He could also join the vibrant racing scene around Puget Sound as the sailboat is way more than a putt-putt boat.

But that is not where Dr. Gallarda is headed. “I’m not interested in racing. I am all about going slow and being present. This boat really puts me in the moment whether I am working on her or sailing,” Dr. Gallarda says. “It’s just the sky, the water and the sail.” Herreshoff would approve.