Words: Captain Chris Couch

Words: Captain Chris Couch

If you want to cruise the world’s truly gorgeous destinations, you’re going to have to master anchoring. One part art and one part science, how one anchors will differ based on numerous factors, but two themes remain constant: scope and location.

Prince William Sound, Alaska, Culross Passage. Fourteen nautical miles east of Whittier. Water depth is 150 feet with a rock and mud bottom. I’m running a 212-foot converted offshore supply boat under contract to Exxon for the second year of the Exxon Valdez spill cleanup effort. The passage is approximately half a mile wide with the wind out of the east at 30 knots, gusting to 50. I have out 500 feet of chain. The engines are on immediate standby in case the winds get worse and we start to drag.

Just west of Dunmore Town, Eleuthera Islands, Bahamas. Water depth is approximately 15 feet with a sandy bottom. Wind is out of the south at 25 knots. I’m running a 60-foot Hatteras Sport Fish and have out about 60 feet of anchor chain. I am still dragging my anchor. Because the water is so warm and clear, I don my snorkel and fins and dive in. I follow the chain forward and, not surprisingly, find the anchor skipping along the bottom like it’s nobody’s business. I return to the boat and put out another 40 feet, which finally stops my slow and unintended slide across the bay.

These two anchoring scenarios could not be more different. One situation has shallow water and a sandy bottom and the other has very deep water with a rocky bottom. One vessel is relatively light with a fiberglass hull and the other is heavy with a steel hull. The common factor that allowed both situations to be executed successfully was proper scope.

These two anchoring scenarios could not be more different. One situation has shallow water and a sandy bottom and the other has very deep water with a rocky bottom. One vessel is relatively light with a fiberglass hull and the other is heavy with a steel hull. The common factor that allowed both situations to be executed successfully was proper scope.

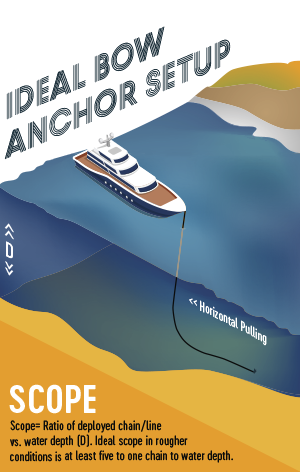

Scope is the ratio of anchor chain or line that is paid out compared to the water depth below the vessel. The rule of thumb is that you start with three to five feet of chain and line per foot of water depth. Wind and current play a very important part in how much scope you use as well. If it is calm with little current, you may get away with a scope of three to four. The more wind and/or the more current, the more scope you will need to use. It is not as much about the anchor, but how the chain lies on the bottom that is the key. The chain needs to lie flat on the bottom and pull the anchor horizontally to hold effectively. With both wind and current pushing on the boat, the more scope or chain you have out, the more chain there is lying flat on the bottom and pulling horizontally on the anchor. The horizontal pull allows the anchor’s flukes to dig into the bottom.

Sucia Island, San Juan Islands. Echo Bay. A summer weekend. The entire western third, the shallow part of the bay, is filled with anchored boats. I am running a 100-foot Broward. The bottom of the rest of the bay is either steeply sloping or is over 100 feet deep. A small, submerged plateau extends north/northwest from North Finger Island. This area rises to a 35-foot depth, and no one is there. It is still far enough in the bay to be relatively sheltered, yet far enough out to escape the usual crowd. I am able to anchor there comfortably using 120 feet of chain for a scope of about four to one.

Location, location, location is the other major factor in anchoring successfully. Before you arrive to the area where you intend to anchor, a study of the chart should be made. Water depth is extremely important for many reasons. You want enough depth to adequately account for any tide range, but it should also be shallow enough to make the best use of the amount of chain you have. Most boats will carry a standard 300 feet of chain. If you anchor in 50 feet of water and need a five to one scope, you use most of the chain that is available. The more chain you use, the bigger your swing circle will be as well. For those of you who have a few feet of chain and mostly line, a considerable amount of extra scope will be needed. Remember that your line weighs almost nothing in the water and will not lie on the bottom. Extra length or scope will be needed to compensate.

Location, location, location is the other major factor in anchoring successfully. Before you arrive to the area where you intend to anchor, a study of the chart should be made. Water depth is extremely important for many reasons. You want enough depth to adequately account for any tide range, but it should also be shallow enough to make the best use of the amount of chain you have. Most boats will carry a standard 300 feet of chain. If you anchor in 50 feet of water and need a five to one scope, you use most of the chain that is available. The more chain you use, the bigger your swing circle will be as well. For those of you who have a few feet of chain and mostly line, a considerable amount of extra scope will be needed. Remember that your line weighs almost nothing in the water and will not lie on the bottom. Extra length or scope will be needed to compensate.

Bahia de Tortugas, halfway down the Baja Peninsula on the west side. This location is the only refueling opportunity between Enseñada and Cabo and is a necessary stop for almost anyone transiting the Baja. I am southbound running a new 54-foot Hatteras Sport Fish with 3412 Caterpillar engines. To get the range I need, I have to idle her at nine knots. This boat is made to go fast and to do that the owners saved on weight by using right-braided hemp line instead of anchor chain. I pull into Turtle Bay with the wind blowing out of the north at 20 to 25 knots. Depth of water is 25 feet with a sand bottom. I have an 80-pound Bruce anchor with 10 feet of chain and 300 feet of line, and end up putting out almost all 300 feet before I get her to hold and stop dragging.

When you arrive at the area in which you wish to anchor, the location of other anchored vessels must be carefully noted. They will all tend downwind and down current. You must always ask yourself, “how will my vessel move on anchor relative to these other vessels if the wind or current changes?” Anchoring too close to other vessels and not taking into account the way they will swing given the wind and current is a common mistake. The trick of eyeballing the right spot with other anchored vessels comes with practice and a few close calls.

Safely picking the anchor back up is just as important as putting it down. I recommend a two-person operation in which one operates and spots the chain and the other maneuvers. Place the vessel bow into the wind or current with the chain tending forward. Ideally you want the chain to tend down and forward to start pulling. Move up on the chain as you bring it up. The person operating the anchor windlass will spot and convey the location of the chain and anchor to you.

Princess Louisa Inlet, British Columbia. A quarter mile south of Chatterbox Falls. I am attempting to anchor and stern tie to the shore a 72-foot Horizon Cockpit Motor Yacht. My stern is approximately 50 feet from the shore. The bottom is rocky and slopes rapidly downward. The water depth goes from 30 feet to 100 feet and continues sharply down just one boat length away. I have almost 200 feet of chain out and a feeling that the chain and anchor are just lying uselessly on the steeply sloping rock face. The wind is calm, but depending on the tide the current pushes me to the left or right. My stern is tied securely to a tree about 80 feet away.

This anchoring method is called the shore tie. The shore tie is used when relatively deep water runs close to shore and/or space is limited, requiring vessels to anchor parallel to each other and secure their sterns to the shore. This method is very popular in the waters of British Columbia, especially the Desolation Sound area. Anchoring in this manner requires a bit more planning. A suitable line of at least 250 feet is needed for the stern line. You need to drop your anchor far enough off the beach so that when you pay out enough scope, you end up neither too close nor too far from the shore. You use your tender to run the line ashore and pick a suitable rock or tree on which to secure it. Pay attention to the tide range so your stern doesn’t end up on the rocks at low tide.

This anchoring method is called the shore tie. The shore tie is used when relatively deep water runs close to shore and/or space is limited, requiring vessels to anchor parallel to each other and secure their sterns to the shore. This method is very popular in the waters of British Columbia, especially the Desolation Sound area. Anchoring in this manner requires a bit more planning. A suitable line of at least 250 feet is needed for the stern line. You need to drop your anchor far enough off the beach so that when you pay out enough scope, you end up neither too close nor too far from the shore. You use your tender to run the line ashore and pick a suitable rock or tree on which to secure it. Pay attention to the tide range so your stern doesn’t end up on the rocks at low tide.

The island of San Andrés, Colombia, 100 miles east of Nicaragua and 200 miles north of Panama. I’m pretty much a dot out in the middle of the Caribbean Basin. I just ran 48 hours from Roatán, Honduras in a 64-foot Offshore Cockpit Motor Yacht. San Andrés is a fuel stop on my way to the Panama Canal. I enter the shallow bay of St. Andrews Harbour and run the three miles north to San Andrés and the small fuel dock. There are already three other vessels anchored and stern tied to the dock, leaving me with about 15 feet of dock left. The water depth is 20 feet and the northeast trade winds are blowing at 15 to 20 knots. The face of the dock runs north and south, so I position the boat about 80 feet or so northeast of the spot I am aiming for with my bow into the wind. I drop the anchor, letting it pay out as I back down toward the dock. Keeping medium tension on the anchor chain, and now within five feet of the dock, we put out cross stern lines to pull us the rest of the way in and make us fast.

This is called the Med Moor, named after the style of moorage used in the Mediterranean where dock space is limited. The Med Moor requires precision placement of the anchor followed by a backing down to put the stern just feet from the dock you are tying to while deploying the right amount of scope to properly hold the anchor. Over the years, I have had to Med Moor large motoryachts seven times in the Caribbean, Central and South America, and Mexico. It was very windy each time. Properly placing the anchor far enough out, upwind and/or up current, is key to success. At least half of my attempts have had to be redone one or more times, including the one I just described.

Knowing just how much chain you have out is crucial to any anchoring operation. Some boats have counters that tell you how much you have let out, but I feel the best and most reliable way is to mark your chain. There are many different ways to mark your chain, but the one I like the most, and the easiest for me to remember, is to mark it with paint. I will use bands of red, white, and blue, then red-red, white-white, and blue-blue, and so forth. Each mark represents 25 feet until the end. Whatever method you use, make it something you can remember. I also highly recommend exercising your equipment on a regular basis to make certain it is operating properly. Run the windlass down and up, and loosen and tighten the brake. I have had occasions where the brake was worn and would start to slip while pulling in the anchor chain.