It appears that the Pacific coast Starfish die-off mystery is solved. For more on this, check out the Earthfix site.

From Earthfix:

SEATTLE — After months of research, scientists have identified the pathogen at the heart of the starfish wasting disease that’s been killing starfish by the millions along the Pacific shores of North America, according to research published Monday.

They said it’s a virus that’s different from all other known viruses infecting marine organisms. They’ve dubbed it “sea star associated densovirus.”

“When you look on a scale of hundreds and hundreds of animals, which we did, it’s very clear that the virus is associated with symptomatic sea stars,” said Ian Hewson, a microbiologist at Cornell University and lead author ofthe study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Figuring out what brings on marine diseases is rare, especially among invertebrates. And identifying what virus is to blame is particularly difficult because a drop of seawater contains about 10 million viruses.

“Basically we’ve had to sort through to try to find the virus that is responsible for this disease,” Hewson said.

To find the culprit virus, an international team of researchers from more than a dozen universities, aquariums, government agencies and other organizations worked together with the help of the National Science Foundation’s coordination network for marine infectious disease.

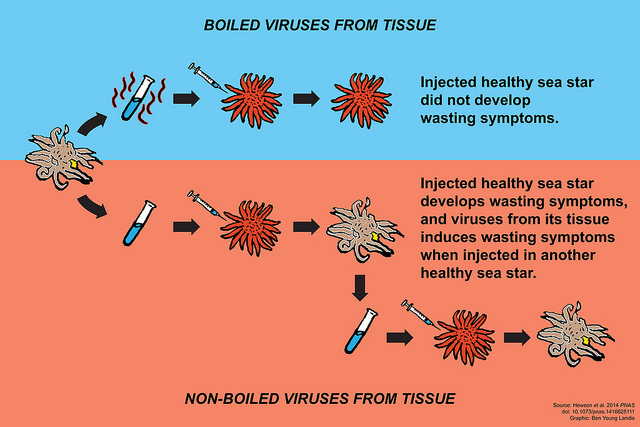

Tissue samples of sick and healthy starfish were analyzed for all the possible pathogens associated with diseased starfish. The team then conducted DNA sequencing of the viruses and compared them to all of the other known viruses. Once they had identified a leading candidate, they tested it by injecting the densovirus into healthy starfish in an aquarium. Then they watched to see if the disease took hold.

And sure enough it did.

“When we inoculated them, they died within about a week to 14 days,” Hewson said. “Whereas controls that had received viruses that had been destroyed by heat, did not become sick.”

When researchers tried to figure out where the virus may have come from, they learned that West Coast starfish have been living with the virus for decades. They detected the densovirus in preserved starfish specimens from as far back as the 1940s.

“It’s probably been sort of smoldering at a low level for a very long time,” Hewson said.

Scientists don’t yet know what sparked the seemingly benign virus to transform into the perpetrator of what’s considered the largest marine disease outbreak ever recorded.

What they do know, Hewson said, is that for about a decade before the first signs of sea star wasting syndrome were reported in the Pacific Northwest, starfish populations here were considered to be overabundant. And they think this might be a clue.

Because viruses often spread by physical contact, when host populations mushroom, there’s greater opportunity for viruses to circulate. There’s also a greater chance that a virus can mutate and become more lethal.

“Predators like this particular virus play a very important role in population control,” Hewson said.

But densoviruses don’t usually cause their hosts to die. What seems to be happening, Hewson explained, is that the sea star associated densovirus weakens a starfish’s immune system. That makes the starfish more susceptible to bacterial infections, which ultimately lead to the gruesome deaths associated with the syndrome – lesions forming, arms falling off and stars melting into piles of mush.

Hewson said it may be possible to use antibiotics to help starfish fight off those bacterial infections.

“That’s not a great strategy for the entire ocean or even small bays and inlets,” Hewson says. “But it does give us some ability to keep them in captivity and potentially grow up resistant stocks in aquariums.”

Scientists will also be watching to see what happens to the next generation of baby starfish that have sprung up in some areas along the Pacific Coast.

“We are interested in the potential for stars to develop resistance to this outbreak,” says Drew Harvell, a marine epidemiologist at Cornell University and the University of Washington who has been coordinating the research. “The only way forward and to have sea stars in the future is for them to develop resistance and having new stars to propagate.”

The research team also plans to continue investigating environmental factors such as warming water and ocean acidification that may have caused starfish to be more susceptible to the viral infection.