There’s a heated debate going on among yachtsmen in clubs and committees all over the world about how to recruit young people to the sport. “Get ‘em young” is one idea, and requires investments in dinghies, instructors, waterfront facilities, not to mention strong financial support from parents.

There’s a heated debate going on among yachtsmen in clubs and committees all over the world about how to recruit young people to the sport. “Get ‘em young” is one idea, and requires investments in dinghies, instructors, waterfront facilities, not to mention strong financial support from parents.

In Astoria, at the mouth of the mighty Columbia River, the Columbia Maritime Museum (CRMM) has found a unique way to interest children from grades 5-7 in boats, geography, navigation, and even international studies. They partner with a school in Japan to assemble 5-foot-long sailing Miniboats to launch on a very long voyage towards each other’s countries, carried by the prevailing winds and currents across the mighty Pacific Ocean.

Miniboats were introduced in 2008 on the East Coast by an organization called Educational Passages, which has enabled classes around the world to launch Miniboats on voyages, mostly across the Atlantic. This caught the imagination of Nate Sandel, CRMM education director, when he first saw a Miniboat at a STEMposium in Portland early in 2017. When he returned to Astoria, Sandel explained to the museum’s directors how this would be a perfect fit for schools around the Columbia River and was given approval to develop the CRMM Miniboat Program, a unique project linking students on both sides of the Pacific.

Sandel started out by developing a curriculum, contacting local schools, meeting the Japanese consul in Portland, and looking for a sponsor to cover the cost of the boats and other expenses. Pacific Power was eager to become the business sponsor, as well as provide their engineers as mentors. The Japanese Consul General in Portland agreed to find partner classes on the northeastern coast of Japan. With this strong backing of the program, Sandel put out a call to fifth grade teachers in Oregon and Southwest Washington to participate beginning in the 2017-2018 school year.

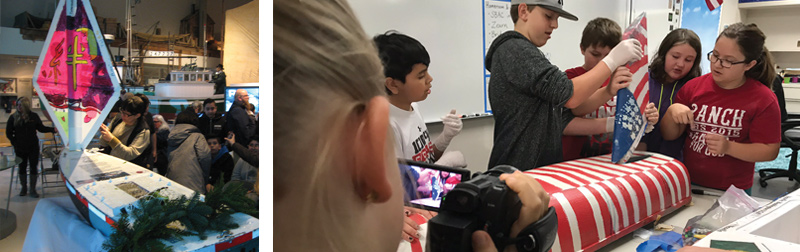

Sit up straight and pay attention, you at the back! This is the way it works for the lucky schools and kids chosen to participate. Each American class receives two bare fiberglass hulls: one it will fit out and launch on the West Coast, and one is brought to Japan for its partner class to launch. Three classes are chosen each year, and Sandel visits them once a week and leads them through the long list of jobs to be completed. He puts students in charge of everything, and encourages them to name their groups as quartermasters, sail designers, keel engineers, cargo trackers, documentarians, etc.

Their boats may be smaller than ours, but their tasks include every aspect of fitting out a bare hull—from sanding and applying anti-fouling paint and topside enamel to attaching the deck with waterproof sealant, working on a large tarp, and wearing aprons and disposable gloves. Some assembly is required – the keel must be ballasted and the mast glued in place. Some students write the press releases for local media and letters to their sister school using Google Translator. Others study weather maps and GPS systems. Finally, the students decide on a name together, pick a drop-off point, and pick out the small gifts and souvenirs they want to pack under the deck before she sets sail.

“At fifth grade, it’s such a year of growth for kids to learn about the world outside of our coastal region,” said teacher Sarah Collins from Gearhart, Oregon. “There are kids halfway around the globe that are just like them and who are participating in the same thing and thinking about us, and we’re thinking about them,” she said. “It’s making them more global citizens versus just kids from Gearhart and Seaside, and has helped them understand science, measurements, and more.”

There is already a remarkable connection between Gearhart and Japan that happened after the 2011 tsunami. A wooden torii (or gate) to a Shinto shrine in Okuki that was carried away by the flood eventually washed up on the Gearhart beach. The Portland Japanese Garden arranged for it to be returned in 2012. The Okuki school is next to the torii, so Sandel chose this school to be the partner to Gearhart. Although the students were very young during the tsunami, they understand that this is an important gift their town has made and that it has won the respect of Okuki’s people.

While the boats are at sea, students on both sides of the Pacific track their progress via the solar-powered GPS units that ping their locations to NOAA satellites. The teachers also work the boats into lesson plans to study weather, maps, math, and more. After three years, Sandel is proud to report that over 1,200 students on both sides of the Pacific Ocean have been involved in the launch of 27 Miniboats, which have traveled almost 60,000 nautical miles—a number that climbs daily.

“While it would be amazing if one of the boats makes it across, the project is really about introducing students on both sides of the Pacific to the wider world beyond their shores,” Sandel reflects. “It’s sort of like sending your kid away to college: this boat has been a weekly part of their life for a whole school year, and it was the kids’ hard work that has made this all happen. So the launch is always a really exciting, bittersweet moment.”

Sandel took the Gearhart boat S/V American Sunset aboard a Columbia River Bar Pilot boat heading out the mouth of the Columbia to the Pacific where it was left to the mercy of the wind and currents. The class chose the mouth of the Columbia with the hope their boat would ride the Alaska Current across the Pacific to the north. Other classes have asked U.S. Coast Guard and southbound freighters to launch their Miniboats off Baja, Mexico, hoping they’ll catch the North Equatorial Current to Japan.

“The Miniboat Program offers an extraordinary way for 5th through 7th grade students in our region to learn crucial STEAM skills, discover future careers, and build international connections that will last a lifetime,” shares Alisa Dunlap, Clatsop County regional business manager at Pacific Power.

“We know STEAM skills are important part of building opportunity for the future, especially in the small communities we serve. We are excited to support a program dedicated to enriching the education of young learners and empowering them to try new things and explore their creativity.” STEAM fields are defined as science and technology, interpreted through engineering and the arts, and based in mathematics.

Every November, Sandel packs up the Miniboats American students build for their partner classes, navigates their bulky shape through airport security, and travels the 4,500 miles to Japan to deliver them himself. He takes his young daughter Hudson along. “She is named after the explorer Henry Hudson,” he explained. Her presence attracts more attention from Japanese of all ages, and they were met and welcomed by many officials, teachers, and pupils. The boats arrive with gifts from the American students in their hull, gifts like books and saltwater taffy. Then the Japanese students finish decorating the boats, seal their own local mementos in the hull, stage their own maritime ceremony, and choose local sailors to set the boats on their course to America.

It might seem far-fetched to think that a tiny boat, glued together and brightly painted by 10 year olds, could sail across the Pacific on its own, but as I was writing this piece on March 8, the Miniboat Facebook page was updated with this message: “We are happy to report that yesterday, S/V Philbert (Columbia City Elementary) and S/V Boat-A-Lahti (from Hilda Lahti Elementary School in Astoria, Oregon, and on its fourth attempt) were launched at sunset off the coast of Mexico by the crew of the U. S. Coast Guard Cutter STEADFAST.”

So more boats are on their way west towards the islands of Micronesia through a world of seagulls and whales, wind and waves. This year’s participants include 7th graders from Warrenton Grade School in Warrenton, Oregon, 5th graders at Columbia City Elementary School in Columbia City, Oregon, and 7th graders from Wy’East Middle School in Vancouver, Washington.

They may still be blown onto the beach in Baja, but some that went before them are more than halfway across. “The boats that crash or hug the shore may give me heart attacks but they’re the really exciting ones,” said Sandel. “That’s because crashing is rarely the end of their story. I promise my students that I will chase down any shipwrecked Miniboat, no matter where it goes.”

Each hull carries a message in multiple languages asking finders to take the Miniboat to the nearest classroom. Then Sandel works with that class and local sailors to get the boat fixed up and back on course. “The cool thing is every time these boats land somewhere, we’re engaging a new group of people,” Sandel pointed out.

The Amazing Voyage of the S/V Nishi Kaze

Words and Photos by Nate Sandel

In 2017, the first year of the Columbia River Miniboat program, the fourth-grade class at Richmond Elementary School in Portland, Oregon, fitted out the S/V Nishi Kaze (“Western Wind” in Japanese). Then the 5-foot-long boat was loaded on the cable ship Decisive that was waiting at anchor in Astoria, Oregon, and finally launched off the coast of Baja, Mexico, on December 2 at a position selected by the students. After sailing west—at least for most of the time—for 398 days and covering 12,672 miles, the GPS stopped transmitting somewhere in Micronesia. Seventy-six days later, the museum received an email message from Monika Eeru, a resident of Tarawa, Kiribati: “We found one boat and a small plastic paper with a piece of paper write on this website.”

Three months later, Sandel found himself on a Fiji Airways flight bound for Tarawa, 5,000 miles from Portland with a layover in Nadi, Fiji. He had five days to locate and repair the Nishi Kaze and send it back out into the Pacific on its way west. Every day was an adventure and he wrote about this amazing experience in the CRMM’s quarterly journal, The Quarterdeck. Very few yachts ever visit these remote low-lying islands, where the sea is never more than a short walk away and small skiffs are the only way to travel between the atolls.

“After thirty-eight hours of travel, we made our final approach into the most beautiful place I’ve ever seen,” Sandel wrote. “The man next to me asked what I was doing traveling to Kiribati–pronounced “kiri-bass.” This island nation is the third least-visited country in the world, so the Kiribati people are always curious when they see i-matang (foreigners). I went into a ten-minute rant about the Miniboats and the one I was trying to rescue. As we got off the plane, the man handed me his card and said to drop by the Parliament Building to visit him. I had been sitting next to Kiribati’s Minister of Commerce!”

At baggage claim, an excessively cheerful, apparently drunk Australian with a wild mustache, and dressed for the outback, introduced himself. “Hi mate—I’m very interested in what you’re doing. If you have any troubles, contact me—I’ve been coming here to work for twenty years, and I know all the locals. I’m at Mary’s Hotel.” Little did Sandel know that the gregarious Gary would become his go-to guy to navigate his way through the local customs and across the lagoon.

Kiribati is the only county in the world spanning all hemispheres. Tarawa, part of the Gilbert Islands, was the setting of one of the bloodiest battles of WWII. The highest point in Kiribati is two meters above sea level, making it one of the most endangered countries in the world. After arriving at his hotel, Sandel set out to hire a boat to take him across the lagoon to North Tarawa, the Miniboat’s reported location. To his surprise, every boatman he asked wanted between $800 and $1,400 for the trip; more money than he had budgeted for or was even carrying with him.

He walked disappointedly back to the hotel in the tropical heat, ordered an ice-cold Fiji Gold beer, and started pondering what to do next. He had only 51 hours left in Kiribati, no transportation, and only the name of a village on a small islet on the other side of the lagoon. Then in walked Outback Gary. “Find yer boat, mate?” he asked. Sandel explained about the high price and his lack of time. “Don’t panic, mate, I’ll find you a boat for $400” — any more than that and he would pay the difference. But first, he had to sort out the water supply at the Australian Embassy!

When he returned, he proudly announced: “Mate, I got the gardener from the embassy to take us in his personal boat for $200 plus $50 for fuel! Hell, mate—we’re going to get your boat back!” The next day, they arrived at the hut of an islander named Bobo who owned the 11’ outboard boat that would carry them to the village of Nuatabu. Nate was relieved to see Gary had found two real life jackets that he tossed into the boat along with food, beer, and a case of water. Bobo reckoned it would take an hour, but it soon became evident that he had not mastered the traditional style of navigation. Luckily, they ran into an old man fishing in an outrigger canoe who pointed the way to the right islet.

A crowd of children welcomed them, and led the way through the village where the i-matang quickly created a stir; a parade formed to escort the strangers to the empty hut where the S/V Nishi Kaze sat. The villagers explained how they spotted it, and that one villager swam out and guided it safely over the reef. Several people signed the new sail Sandel was carrying, they exchanged small gifts, and it was time to head back to Bobo’s boat to beat the tide back across the lagoon.

A tropical squall hit 30 minutes later. The waves kicked up, and they were pelted with rain that would scare an Oregonian. The islands disappeared in the downpour, and several waves nearly capsized the boat. When they arrived back at the wharf none the worse for wear, the Minister of Commerce and his wife were waiting, having heard through the island grapevine that they had left to get the Miniboat.

Sandel spent the evening repairing the Nishi Kaze for the relaunch the next day. He opened the cargo hatch and found the AP3 GPS transmitter had come away from its mount. He built a new, more secure base for the new transmitter, switched out the sail, and applied a coat of bottom paint. Strolling around town that night, he felt confident that the mission could be completed—with Gary’s help.

Early the next day, Gary was back and raring to go. He had located the perfect spot to launch at the southern tip of the atoll. When they arrived, he parked the Subaru Forester and tried carrying the boat the mile-long walk over coral to reach the open ocean. By now, Sandel was thinking more like a local, so he climbed over the road barrier, dropped the Miniboat into a channel, and began swimming it towards an opening in the reef, under the watchful eyes of three fishermen. He gave it one more big push to send the boat on its way, but the Nishi Kaze was reluctant to leave and turned back towards the reef.

One of the fishermen stripped down, dove in the water, and swam over to the foreigner who, despite all his efforts and hopes, was about to be smashed into the reef along with the boat. “Hold my flippers,” the man said. He swam to the Nishi Kaze, grabbed the keel and pulled it to safety. Then he swam fifty meters out to sea where the Miniboat immediately caught a gust and took off like an outrigger canoe catching the trade wind.

“It was an out-of-body experience,” Sandal recalled. “At that moment, I reflected on the meaning of the Nishi Kaze to those kids, and the overall meaning of the project. This Miniboat, built by kids in Japan and the United States to foster friendship between them, was now sailing away from Tarawa, where 75 years ago 6,000 of both our countrymen died fighting each other.” He learned later that the fisherman was the Police Inspector for all of Kiribati—yet another connection with this model boat that had set so bravely from Oregon thousands of miles and world away. “I was blown away by the seemingly impossible co-existence of poverty and happiness. The Kiribati have very little, but are still the happiest people I have ever met,” he wrote.

Nate Sandel is a graduate of Central Michigan University and has worked at the CRMM since 2005. He has taught in 37 states, five countries, and counting. For more information visit crmm.org or email sandel@crmm.org.