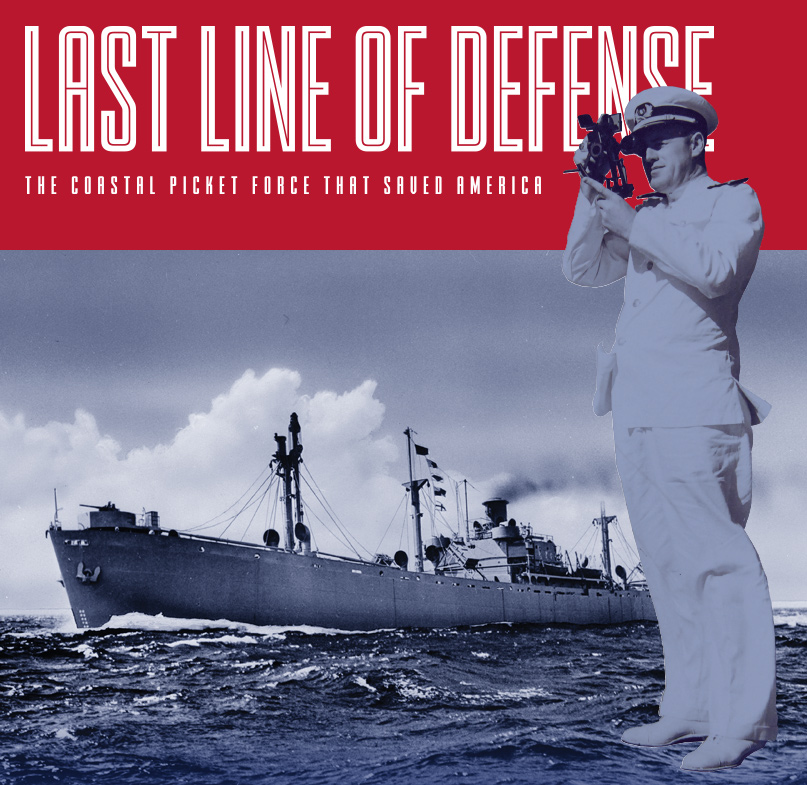

A dwindling number of the civilian boaters, mariners, and sailors who formed a line of defense on America’s coasts and inland waters during World War II are alive today, but as they leave the living’s ranks, their heroism and deeds are not forgotten.

A dwindling number of the civilian boaters, mariners, and sailors who formed a line of defense on America’s coasts and inland waters during World War II are alive today, but as they leave the living’s ranks, their heroism and deeds are not forgotten.

Fishermen, sailors, and motorboat skippers that stepped forward to keep watch along America’s coastlines have stories that are an essential part of the Great War’s history. There were deckhands and enginemen; machinists and pipefitters; near-coastal and deep-sea fishermen; sailors and powerboaters; along with the Merchant Mariners who pick up the call to defend America’s shores. While they came from different walks, these civilians had much in common: They were all mariners, members of the cult of the sea, and they loved their country.

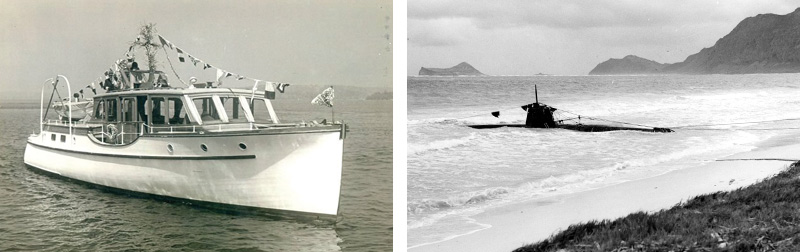

Make no mistake: America’s domestic security was fraying in 1941. The week following the attack on Pearl Harbor, nine Japanese submarines attacked U.S. merchant ships along the Pacific Coast. One sub shelled an Army base and a beach in Oregon, another shelled a park in Santa Barbara, California.

Over a period of seven months in 1942, German U-boats torpedoed and sank 233 merchant ships on the Atlantic Coast and in the Gulf of Mexico, the New England Historical Society reports. The loss of ships carrying Gulf crude oil slowed wartime production and resulted in gasoline rationing.

The human cost was great. “The U-boats killed 5,000 seamen and passengers [in 1942], more than twice the number of people who perished at Pearl Harbor,” according to the historical society.

The United States had a massive coastline to protect and, with its fleet engaged in war, not enough Coast Guard cutters and Navy ships to do it. Sailors, fishermen, and yachtsmen stepped forward to turn the tide, and soon a fleet of about 3,000 motorboats, racing yachts, and fishing schooners was patrolling inland and coastal waters, watching for enemy

submarines and rescuing survivors of torpedo attacks.

It was called the Coastal Picket Force, aka the Corsair Fleet, to which the Chief of Naval Operations assigned oversight to the Coast Guard Reserve.

Corsair Fleet boaters and sailors “were crucial to the Coast Guard as submarine spotters,” journalist Troy Gilbert wrote in a 2015 edition of BoatUS Magazine, “and they were highly effective at rescuing survivors from the lost ships throughout the war.” The Pioneer, a fishing yawl given the designation CGR-T-2267 by the Coast Guard, rescued all 44 crew and passengers from the R.M. Parker Jr. when the steam tanker was sunk by two torpedoes from U-171 about 25 miles south of Isles Dernieres, Louisiana.

Off Florida’s shores, Corsair Fleet sailors “patrolled thousands of miles of otherwise unprotected beaches,” according to Dr. David J. Coles of Florida’s World War II Memorial. Among those on watch for German U-boats was novelist Ernest Hemingway and crew on his 38-foot fishing boat Pilar.

Gilbert reported this account of Corsair Fleet heroism: “In one instance, when a Mexican tanker lay engulfed in flames and rapidly sinking just off the beaches of Miami, hundreds of citizens watching in horror witnessed the local flotilla drive their little boats right into the flames to retrieve survivors.”

The Corsair Fleet freed up the Coast Guard to actively hunt marauding U-boats, and the tide started to turn. U-boats were sighted and sunk off the coasts of North Carolina, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island. “Because of their presence off the coast, [German] submariners knew that they couldn’t safely cruise the surface at night,” author Gabe Christy reported in, Corsair Fleet – The Brave American Civilian Crews Who Took On WW2 Submarines To Protect The Coast. “And the merchant seamen they were targeting knew that if they sank, there was likely a picket ship nearby which would rescue the survivors.”

By the end of 1943, Christy wrote, “the submarine threat had significantly diminished.”

The Civil Air Patrol, a civilian fleet of privately owned aircraft, played a key role in bolstering coastal security and defense. Patrolling the coast from Maine to Florida, civilian pilots “flew 86,865 missions, sighted 173 U-boats, reported 91 ships in distress and 17 floating mines and rescued 363 survivors of U-boat attacks,” the New England Historical Society reported. “Ninety planes were lost on those missions, and 26 people died.”

Rather than seeing their boats requisitioned by the Navy, yachtsmen in Puget Sound accepted commissions as reserve officers and remained at the helm of their vessels, doing patrol duty in waters they knew very well.

Reuben J. Tarte, founder of Transport Storage and Distributing who would go on to own and transform the lime company town of Roche Harbor into a boating resort after the war, patrolled Puget Sound in his Ed Monk-designed 38’ cruiser Clareu II. “He was commissioned as a lieutenant commander so he could continue [at the helm of his cruiser],” grandson Neil Tarte Jr. recalled last May. “We have home movies of when he was commissioned, along with movies of the Clareu II with the hull painted black.”

The Navy benefitted from Puget Sound yachtsmen’s knowledge of local waters. And the presence of the Puget Sound picket fleet can’t be overstated. Puget Sound was — and is — the gateway to a Navy base, a submarine base, a major naval shipyard, and other Navy, Army and Coast Guard installations. At that time, nine Japanese submarines were strategically stationed along the U.S. Pacific Coast, and among them, the I-25 submarine off the mouth of the Columbia River and the I-26 sub off the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Between June 20 and Oct. 5, 1942, I-25 torpedoed three merchant ships, sinking two, and shelled three sites in Oregon, including Fort Stevens.

It wasn’t the first time U.S. yachtsmen had come to the nation’s aid in wartime. “During the American Civil War, private American yachts were loaned or leased to the U.S. Navy,” according to C. Kay Larson, national historian of the U.S. Coast Guard Auxiliary. The 1916 Naval Reserve Act provided for enrollment of civilian boats and crews “suitable for naval purposes in the naval defense of the coast.”

During the Great War, the U.S. Naval Reserve organized yacht clubs into submarine watches “to ease fear along the coast and raise morale by giving everyone a greater piece of the action,” Larson wrote.

During the Great War, the U.S. Naval Reserve organized yacht clubs into submarine watches “to ease fear along the coast and raise morale by giving everyone a greater piece of the action,” Larson wrote.

The timing was right for a civilian marine defense. In the 1920s, the Chris Craft Company began the mass manufacturing of recreational boats. “By 1936, the family cruiser had become the backbone of the U.S. motorboat industry,” Larson wrote. “These cruisers would become the backbone of the [nation’s] small-boat fleet.” Without them, “America would not have been able to provide the vessels that protected its coasts during World War II.”

The U.S. Merchant Marine, the civilian mariners who operate the nation’s fleet of civilian and federally owned cargo and passenger vessels, can in times of war be an auxiliary to the Navy and called upon to deliver military personnel and material. During World War II, the Merchant Marine suffered a higher casualty rate – 1 in 26 – than any other branch of the military, “with most of the losses occurring in 1942, when most merchant ships sailed U.S. waters with little or no protection from the U.S. Navy,” William Geroux wrote in his book, The Mathews Men: Seven Brothers and the War Against Hitler’s U-boats.

Despite the dangers, Merchant Mariners were undaunted. “Many of the mariners who survived torpedo attacks went right back to sea, often sailing through the same perilous waters, only to torpedoed again,” Geroux wrote. “One mariner was torpedoed ten times.” Merchant Mariners received gunnery training at schools in Alameda, California; Catalina Island; and Sheepshead Bay, New York. They became adept at handling 30- and 50-caliber machine guns, .20-millimeter anti-aircraft guns, deck guns, and cannons.

A publication for trainees at the Avalon U.S. Maritime Service Training Station on Catalina Island, California, stated, “America’s seamen are being trained for a fighting Merchant Marine, a promise that the goods will be delivered … Give a man a gun and teach him how to use it.” Vice Adm. Albert J. Herberger, USN (ret.), wrote on the American Merchant Marine At War website (usmm.org) that Merchant Mariners also received on-the-job training while under attack.

They assisted Navy personnel in passing ammunition, caught hot cannon shells after firing (while wearing asbestos gloves), and were assigned anti-aircraft gun stations. “In responding to attack by the enemy, Navy personnel and Merchant Mariners fought together as a team – they were members of the same gun crews,” Herberger wrote. “The exchange of gunfire, especially in the first two years of the war, was a daily routine for many of the merchant vessels.”

Harlan Wesley Bowers (1926-2006) received Merchant Marine training at Avalon in 1943 and was assigned to the Army Transportation Corps. “Was on TP 103, a seagoing wooden tug [with a] Fairbanks diesel engine,” he wrote late in his life. “From the Stockton, California shipyard, we sailed to New Guinea, then up the coast on several invasions, then made up a small ship convoy and went on the Leyte invasion in the Philippine Islands.

“Sailed in a small ship convoy to Okinawa, Naha [Bay]. One of only two ships to make it. We towed a Navy tug and barge there. Was transferred to the USS Octorara in Leyte, sailed to Okinawa, Naha Bay, then back to Manila several times. We were sent to San Pedro and were outfitted for the invasion of Japan.”

According to a U.S. Navy history, the Octorara (IX-139), which Bowers was on, arrived in San Pedro Bay, Philippine Islands, on June 10, 1945 to prepare for Operation Downfall. The operation, an Allied invasion of Japan, was cancelled after the Empire surrendered.

“Throughout the Second World War, our Armed Forces relied on the Merchant Marine to ferry supplies, cargo, and personnel into both theaters of operation, and they paid a heavy price in service to their country, said John Garamendi, a California Democrat who represents the Sacramento area in the U.S. House of Representatives.

“The Merchant Marine suffered the highest per capita casualty rate in the U.S. Armed Forces during World War II. An estimated 8,300 mariners lost their lives, and another 12,000 were wounded, to make sure our service members could keep fighting. Yet, these mariners who put their lives on the line were not even given veteran status until 1988.”

The number of Merchant Marine casualties in World War II vary. According to American Merchant Marine At War website, 9,521 Merchant Mariners were killed and 712 were taken as Prisoners of War. As of January 2020, there are 4,000 remaining Merchant Mariners who served during WWII, according to congressional estimates.

A bill introduced by Garamendi would award the Congressional Gold Medal to the surviving Merchant Mariners of World War II. The bill was passed by the House of Representatives and moved on to the Senate on January 28, 2020. (Surviving Civil Air Patrol pilots of World War II received the Congressional Gold Medal in 2004.) In his announcement of the bill, Garamendi told of meeting three World War II Merchant Mariners: Eugene Barner, 92, of Kansas; Charles Mills, 97, of Texas; and Robert Weagant, 92, of Illinois.

“These mariners put their lives on the line for this country, braving German and Japanese submarines in their Liberty Ships as they delivered critical supplies to our service members in the European and Pacific theaters,” Garamendi said. “Unfortunately, their sacrifice is commonly overlooked. A Congressional Gold Medal would give them the recognition they deserve, and that’s why I introduced this bill: to give these veterans and their families the honor and respect they are owed.”

Christian Yuhas, vice president of American Merchant Marine Veterans and a chief engineer Merchant Marine, called Merchant Marine veterans of World War II the “unsung heroes” of the war who “nobly served our country by operating the ships that transported critical supplies to front lines of the war, and in doing so suffered a casualty rate higher than any other branch of the military.”

Christian Yuhas, vice president of American Merchant Marine Veterans and a chief engineer Merchant Marine, called Merchant Marine veterans of World War II the “unsung heroes” of the war who “nobly served our country by operating the ships that transported critical supplies to front lines of the war, and in doing so suffered a casualty rate higher than any other branch of the military.”

The Coastal Picket Force became the Coast Guard Auxiliary. The Civil Air Patrol is an auxiliary of the U.S. Air Force. And each Merchant Mariner, before he or she receives a Merchant Mariner Credential from the U.S. Coast Guard, takes the same oath as those who served in World War II:

“I do solemnly swear or affirm that I will faithfully and honestly, according to my best skill and judgment, and without concealment and reservation, perform all the duties required of me by the laws of the United States. I will faithfully and honestly carry out the lawful orders of my superior officers aboard a vessel.”