Girls belong on boats, and there’s no person in history that tells this story better than Tracy Edwards, the British sailor and skipper who assembled an all-women crew to race the Whitbread Round the World Race in 1989 on Maiden.

Girls belong on boats, and there’s no person in history that tells this story better than Tracy Edwards, the British sailor and skipper who assembled an all-women crew to race the Whitbread Round the World Race in 1989 on Maiden.

This very same 58’ ocean yacht graced our Puget Sound waters in August, having just completed Leg 6 of the Maiden Factor World Tour. The tour, which began in the UK in November 2018, includes 32 destinations in 17 countries and will conclude in the Mediterranean Sea in May 2021.

The Maiden Factor World Tour is designed to raise awareness about girls and the importance of education. With the mantra, “Educate a Girl, Change the World,” Maiden has set sail around the world to bring a message of hope to young girls around the globe.

As Maiden travels from port to port on this tour, kids are being asked to write a message of hope to be shared with just one person who may be considering walking away or giving up on school. These letters are being collected and will be published in a book following the completion of the Maiden Factor World Tour.

I was lucky enough to jump on board Maiden for Leg 6 out of the 28-leg tour of the Maiden Factor World Tour (Vancouver, B.C., to Seattle, Washington). For me, the voyage was an experience cemented with long-lasting memories.

Tracy Edwards was only in her early twenties when she helmed Maiden and proved to the world that anything is possible. Inspired by her friend, King Hussein I of Jordan, she skippered Maiden with the first all-female crew ever in the Whitbread Round the World Yacht Race in 1989 and 1990.

With unwavering tenacity, determination, and hard work, Edwards and her crew raced 32,932 nautical miles in the Whitbread that year, winning two of the most difficult Southern Ocean legs and placing second overall in their division. This feat was accomplished in a refurbished 58’ Bruce Farr ocean yacht that the team gutted and rebuilt together. Women’s sailing was never the same.

Much has transpired since Maiden’s success in the Whitbread. Edwards received the coveted Yachtsman of the Year trophy. She wrote two books, started a family, and managed sailing programs. She became a motivational speaker and life coach. She eventually sold Maiden and later found her in grave condition in the Seychelles in the Indian Ocean, so she bought her back. And then for a second time, Edwards gutted Maiden and rebuilt her into the state-of-the-art modern sailing yacht that she is today.

In November 2018, the documentary Maiden was released, directed by Alex Holmes and produced by Sony. Despite the movie being completely independent of Tracy Edwards and the Maiden Factor Foundation, the timing of the release couldn’t have been better because the publicity from the movie has provided a much-needed fill on Maiden’s sails.

The Maiden Factor Foundation works with six charities who provide outreach to ensure that girls are getting a quality education. At the heart of this education spotlight is Edwards’ own story as a young girl, following the death of her father when she was only 10 years old.

Edwards turned into a rebellious youth who was suspended from schools so many times that she was eventually expelled altogether. And despite her mum’s unwavering support, Edwards turned her back on an education and left home. “I feel that I was so stupid to throw away a free education,” offers Edwards when I asked her about this time in her life. “Of course I didn’t understand it at the time.”

I first heard of Maiden in 1989, the year I graduated college. What caught my eye was a photo in a magazine of a group of women sailors all wearing bathing suits. At first glance, I thought it was an ad for an activewear line. But I soon learned that it was more than just a pretty picture. It was a picture reflecting the bravest and smartest women sailing team I had ever seen.

I met up with the Maiden crew in Vancouver, B.C., in early August 2019 following their Pacific Ocean crossing from Hawaii. Maiden’s crew max is nine, but they made an exception for me since I was armed with a press pass and my own sleeping bag. This number includes five permanent crew and four guest crew. The permanent crew are handpicked by Tracy Edwards herself, and the guest crew is determined by a selection process requiring the submission of a personal sailing CV and medical questionnaire.

In addition to those sailing, there is a shore support team, led by Shore Manager Allie Smith. This team is responsible for all the logistics of Maiden’s comings and goings from port to port and the setting up of the Maiden Factor Foundation outreach events in schools and yacht clubs around the world.

Stepping aboard Maiden for the first time was a rare and special treat, like sampling a Knipschildt Chocolatiers truffle. The skipper, crew, boat, and mission all combined made for an experience that I won’t soon forget.

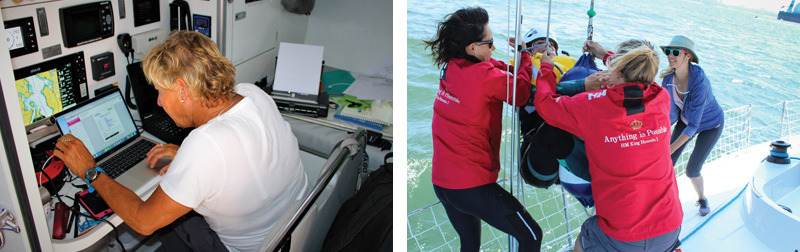

We were a crew of ten, representing five different countries. Permanent crew included Skipper Wendy (Wendo) Tuck (Australia), Rigger Matilda (Tilly) Ajanko (Finland), Safety Officer Belinda (Belle) Henry (Australia), and Onboard Reporter, Amalia Infante (Spain). Guest crew included Tracy Edwards’ 19-year old daughter, Mackenna (Mack) Edwards-Mair (UK), Jessica Karyn-Costa (Canada), Janet Heloe-Clendenning (Canada), Arielle Fraser (Canada), Debra McKenna (Canada), and me, Schelleen (Schell) Rathkopf (USA).

“Don’t go running around here like a crazy person or you’ll fall overboard,” Skipper Wendy bellowed to the new crew. “And put your crap away and keep your stuff off the chart table. We all have our thing and that’s my thing.” When Skipper Wendy speaks, everyone listens. She has ten Rolex Sydney Hobart Yacht Races under her belt in addition to a couple Clipper Around the World Races, one of which she won in 2018 as the first woman to ever win an Around the World sailboat race. She hooked up with the Maiden Factor effort in March this year.

Maiden and her permanent crew are a well-oiled machine. But the most challenging part for this crew is the introduction of a whole new set of guest crew at the start of each delivery leg. In the interest of safety and organization, having a rigid protocol in place keeps order on Maiden as these crew changes take place.

We began the preparations for our delivery from Vancouver, B.C., to Seattle. We were assigned a hook to hang our foul weather gear and PFDs on and a roll call number if a headcount was needed. We were put in teams for the watch rotation and set up a bunk, cubby and crew box to stow our stuff.

Before departing, we spent a day together on board to get to know the yacht and practice man overboard drills. Provisions were loaded, the rigger was hoisted up the mast to check on the standing rigging, and system checks were completed. Finally, to complete the send-off preparations, Maiden and her crew participated in a Native American brushing ceremony that involved the brushing of the boat with cedar boughs and later, the release of the cedar boughs in transit through the waterways.

We shoved off from Vancouver Rowing Club at approximately 1630 on August 6, anticipating an estimated ETA in Seattle by 1000 the following day. For the permanent crew who were accustomed to spending weeks on the boat at a time, this leg was like an easy commute home from a day at the office.

Tracy Edwards’ 19-year old daughter Mack was on board for this leg because “it’s the shortest!” As Mack is now working for her mum at the foundation, it was a condition of her job that she be on board Maiden for one of the legs. Despite her mum’s long history on boats, Mack is deathly afraid of the water and not 100 percent comfortable on a sailboat.

Our route followed the shipping lanes from Strait of Georgia, through the San Juan Islands via Rosario Strait, then the Strait of Juan de Fuca, Admiralty Inlet and into Puget Sound and Elliott Bay. We started out with clear skies, a gorgeous sunset, and an occasional porpoise sighting but as the night wore on, this soon turned to heavy fog and bumpy seas due to the breeze and the notoriously devilish currents.

I was at the helm for a good portion of the 0230 to 0530 hours watch, when it was the roughest, and drove with my eyes fixed solely on the instruments. It definitely got sporty for a spell, but I loved every minute, knowing that I was with a team of sailors who really knew their stuff.

Maiden has a tradition to fly the nation’s flag in whose waters she is sailing. The border crossing ceremony involves the entire crew on deck, and one crew member is chosen to handle the flags and sing the national anthem of the new country.

As I was the only U.S. citizen on board, I was asked to handle the flags on Leg 6 and sing the Star-Spangled Banner for this ceremony. The pressure was on, but despite a few cracks on the high notes, I’m certain the crew appreciated the effort. It was an honor I will never forget.

And, as expected, the topic of sailing with all-women crews came up from time to time. “Women crews are just more empathetic, supportive, and encouraging,” Heloe-Clendenning said. “I like sailing with both men and women, but women are just really good sailors.”

Fraser added, “There seems to be more camaraderie and less ego involved with all-women crews.”

When asked why there aren’t more women boat owners, Karyn-Costa chimed in, “Women are too smart to throw all their money into a boat!”

Most of the crew on Maiden had significant offshore experience. As a fair-weather recreational sailor with some racing and cruising experience, I found the experience onboard Maiden to be completely satisfying. With Maiden, Tracy Edwards changed the face of the sport and proved that women could be equal competitors in a sport historically dominated by men. And nowadays, they’re not making a difference just because they’re women. They’re making a difference because they’re just damn good sailors.