On a clear January day, I stood with a dozen people in the boat shop of the Wagner Education Center, a newly opened facility of the Center for Wooden Boats (CWB) in Seattle. The shudders were raised on the huge glass windows that circled the room, filling the shop with winter sunlight.

On a clear January day, I stood with a dozen people in the boat shop of the Wagner Education Center, a newly opened facility of the Center for Wooden Boats (CWB) in Seattle. The shudders were raised on the huge glass windows that circled the room, filling the shop with winter sunlight.

We were all students in a woodworking class, part of the Kitten Boatbuilding Project, here to learn how to construct a small sailboat using traditional tools and techniques. We gathered around a white board as the instructor, shipwright Ben Kahn, explained the details of the day’s project.

I confess, I felt a little in over my head. Building the boat takes place over the course of many classes, and I’d joined in about halfway through. Many of the other students had been participating since the beginning. “Okay, today we’ll begin the planking work, which means we need to make some patterns,” Kahn says.

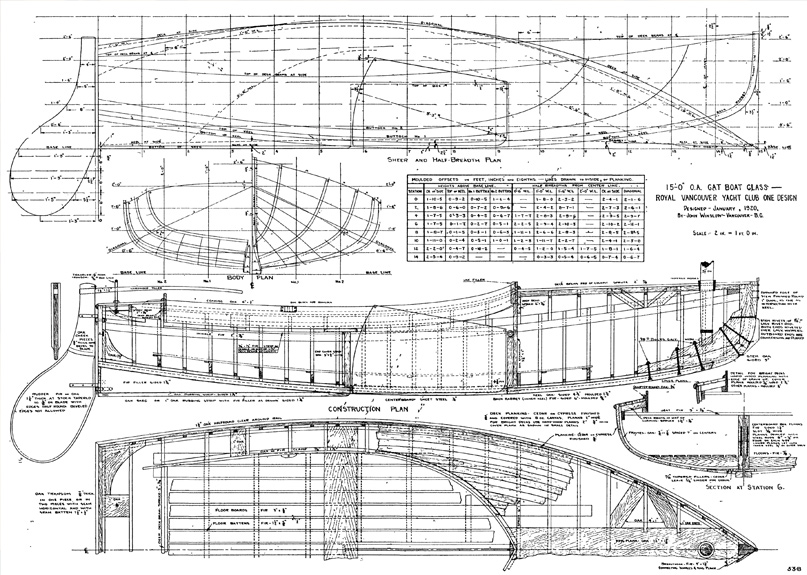

The last time I was in a woodshop was middle school, where the most complicated thing I made was a cutting board. Now I was in a class focused on building a historic catboat design, common in British Columbia and Puget Sound waters a century ago. The kitten-class boats were designed in 1920 by John Winslow, a member of the Royal Vancouver Yacht Club.

Winslow suggested the kitten as a one-design sailboat for racing and afternoon sailing to draw in new members. The yacht club agreed and ordered 15 of the boats.

The kitten-class boats were soon championed by other yacht clubs in British Columbia and Washington, becoming a permanent class in the Pacific International Yacht Association. In the July 1920 racing season, the kitten-class boats provided some of the best racing of the season. Two years later, Winslow moved to Seattle and brought a small fleet of kittens with him.

“Okay, does anyone have questions?” Kahn asks as we begin our work. “Who would like to work on creating a pattern for the shear?” We break off into pairs and I was partnered with a man named Scott. We decided to make the shear, the top plank farthest from the keel. As we started to get to work, I walked over to get a look at the kitten under construction.

The boat was being built upside down. Previous classes constructed a strongback and molds, on which the keel of the kitten rested. Thin wood beams called ribands ran horizontal with the floor and attached to the molds. Pieces of white oak, that comprised the frame, were steam bent around the ribands and attached perpendicular to the keel, like ribs attached to a backbone.

Before we began our work, I went to examine the original kitten the CWB had managed to save. The boat was nearing its centennial with a badly damaged hull, and it hadn’t been in the water for years.

It could have been a member of the fleet Winslow brought with him to Seattle, or one built later. When he moved to the area, Winslow brought his fleet to the Seattle Yacht Club, where he quickly befriended local sailors. Shortly after, he teamed up with iconic Seattle boat builders Ted Geary and Norm Blanchard to create a new fleet of kitten-class boats.

These boats were used to teach sailors the fundamentals of sailing technique, their wide beam making them especially difficult to capsize and quite safe for novice sailors. Many members of the Seattle Yacht Club had their first sailing lessons in these well-loved boats.

Back in the boat shop, work on the new kitten was underway. Scott and I picked up a long, thin piece of flexible plywood called doorskin, and we used it to make a pattern for what would become the shear. We attached the piece of doorskin to the frames of the kitten, where pencil marks dictating the shape of the shear had been made.

We glued tabs, smaller pieces of wood, onto our pattern so the dimensions would perfectly match those of the imagined shear that had been sketched out. Several hours went by as we paid careful attention to details. I started to realize how time-consuming building boats truly is and the skill required to work with wood. I looked around at the activity in the shop and began to imagine the Lake Union boatyards of a century ago working on the fleet of catboats.

For many young sailors in Vancouver B.C. and Seattle, the kitten boats provided their first experience skippering their own boat in a race. A number of the boats purchased by the Seattle Yacht Club were used in the club’s racing series. A 1920 article by Winslow, published in Pacific Motor Boat, describes the action: “While the Seattle Yacht Club only built five boats this year, these boats nevertheless provided some very interesting local races and aroused much enthusiasm in the new class…”

He also mentions that most of the sailors in the series were the junior members of the yacht club, with the 12-year-old Jack Graham Jr. winning the series and beating many of the adults. Winslow points out that the simple set-up of the kitten boats and the speed in which they can be prepped and launched tempted many of the old-timers, who couldn’t resist the chance to get back out on the water.

Another article published a year later, again in Pacific Motor Boat, is the first-hand account of 13-year-old Billy Freeman, his friend, and his father, Miller Freeman of the Seattle Yacht Club, cruising the San Juan Islands in a kitten boat, showing the versatility of the design.

The editor’s note at the beginning of the article states: “No one feature has accomplished so much in enlisting the interest of the junior members of the yacht clubs of British Columbia and Puget Sound as the development of the Kitten Class.”

As Scott and I worked to finish the pattern for the shear, other students made progress on their own assignments for the day. Two others had cut a plank using a pattern made in a previous class and were heating up a steamer to warm the plank. The plank would need to be carefully bent to fit the lines of the boat and warm enough so not to crack as it was being put in place.

Other students worked on side projects, sanding old boats in the shop for a restoration. Kahn stood by the new kitten and explained how a water-tight seal was made. “In the past, shipwrights would take long strands of cotton or spun oakum and drive them into the seams between the planks,” he says.

“Then the gap was filled with a layer of pitch or anything that stayed flexible when exposed to water. Today we use a modern seam compound.” He added that even the best sealed wood hull still leaked and needed to be constantly monitored.

We finished making our pattern, then moved it over to a board that would eventually become the shear, after our pattern was traced onto the board. I was starting to see the bigger picture and the many steps that went into making just a single piece of the boat. The sounds of antique tools at work and the smell of sawdust hung in the air as the day slowly began to wind down.

Scott and I continued our work on the shear; the correct shape was marked off in pencil on the board and nails hammered into the marks. A long, thin piece of wood called a batten was run along these nails, and a second set of nails were hammered in above the batten, holding it in place.

Pencil was used to trace along the baffen, finally giving us the shape of the shear that would be cut from the board. That, however, would have to wait for another day, as the sun was beginning to set.

As I walked over to the original kitten once again to take a picture, I was struck for the first time that day how much it and the kitten under construction were starting to look alike.

I began to see the symmetry in both boats, knowing the process the builders of the first boat had undertaken, because I had just done a few of them myself. I wondered if the builders of that boat knew that it would last for 100 years and become the focus of admiration for a group of boat lovers and history enthusiasts?

My thoughts turned to the boat-to-be behind me. How long would it last, and will people of the 22nd century look at it? This sense of continuity was exactly the point of this class and others like it, the reason living museums have such a draw, and why so many people spend their free time to return a missing piece of local boating history back to the water.

As we wrapped up for the day, Scott observed a small knot in the wood we had been working with. He called Kahn over, who made the judgement that the knot would likely interfere with the bending of the shear after steaming. We would likely have to start over and flip the pattern in order to dodge the knot. I laughed to myself as hours of work were cancelled out in a final, fitting hiccup that perfectly illustrated the frustrations and satisfaction involved in anything worth doing.

The sun was setting now and the shop lights turning off as I took one last look at the piece of boating heritage slowly being brought back to life.