As fate would have it, I started to write this article right when I booked a delivery from Seattle to Portland. Thanks to my career as a yacht delivery captain, this would be my 58th such trip across the entrance and transit of the Columbia River.

As fate would have it, I started to write this article right when I booked a delivery from Seattle to Portland. Thanks to my career as a yacht delivery captain, this would be my 58th such trip across the entrance and transit of the Columbia River.

This time around, I tried to imagine what Bruno de Heceta, the first European to describe the Columbia River entrance in 1775, saw that day. For me, 243 years later, the wind is calm with a visibility of 30 miles on the day I cross the entrance. The water is glassy with a long-period six-foot swell out of the west. The sky is clear with a line of cumulus clouds forming over the shoreline. I am eight miles offshore, southbound 25 miles from the entrance to the river. With the lowlands of Long Beach and Willapa Bay to the north, the river delta to the south and east, and the high terrain of Cape Disappointment and North Head, first impressions are deceiving. The entrance is so wide and the lower river so expansive that, except for the challenges of crossing, it looks like a very large bay or inlet.

I was first introduced to the Columbia River back in the 1980s as a young chief petty officer in the U.S. Coast Guard (USCG). My first trip across the Columbia River Bar entrance was in a Coast Guard 44’ Motor Lifeboat from the National Motor Lifeboat School in Ilwaco, Washington. The USCG National Motor Life Boat School was established in 1982 and teaches search and rescue boat coxswains from all over the world how to safely negotiate heavy surf conditions with “The Bar” as a classroom. I was very fortunate that I learned how to safely cross West Coast bar entrances from the experts, acquiring knowledge that would serve me well later as a West Coast delivery captain.

I would first cross the Columbia River entrance as a delivery captain in 1996, running inventory back and forth between Portland and Seattle for Ocean Alexander. Twenty-two years and 58 crossings later, I still get a little anxious before each transit.

There is a reason the Columbia River entrance, The Bar, is called the Graveyard of the Pacific. Part of what makes that entrance so hazardous is the sheer volume of water flowing in and out. When an outgoing water current meets an incoming wave or swell, that wave is slowed down. When a wave slows down, it builds. So, on an ebb tide when the current is going out along with the natural river outflow, that current builds the incoming waves right at the entrance area. This is what happens at all bar entrances and wherever water current flows against a wave pattern.

As notorious as the West Coast bar entrances can be, especially the Columbia River, crossing them can be done safely each time by following a few simple rules:

Rule #1: Always plan to transit the area during a slack or flood tide. The incoming current helps to reduce the size of the waves at the entrance.

Rule #2: Always pick good sea conditions outside. The size of the waves at the entrance is directly related to the speed of the outgoing current.

Rule #3: Always transit in daylight.

Adhering to these rules will ensure that your bar crossing experience is a good one. Safely across The Bar, one immediately passes the small port of Ilwaco, Washington. Ilwaco is a favorite for boaters waiting overnight or for weather to cross the entrance to continue north or south along the coast. I usually continue ten miles upriver to the West Basin Marina in Astoria to fuel up, moor overnight, and dine at the Bridgewater Bistro.

The run upriver to Portland is approximately 85 nautical miles. In the 22 years I have been doing that run, the dozens of little isolated sandy wooded islands and hundreds of miles of deserted sandy beaches have always interested me. Most of these sandy islands were created by the dredging of the river over the years. I often see boats anchored just off these beaches, campers on the beach, and people fishing.

There is no shortage of places to stop on that stretch, from the hundreds of possible anchorages to the numerous small towns and ports along the way. Aside from Ilwaco and the West Basin in Astoria, most of the marinas are small and designed for smaller vessels. The towns of Rainier (across the river from Longview) and Saint Helens, however, both have public docks with plenty of side tie space.

The Columbia River can be thought of as two major sections; namely the lower river which runs from the entrance to just east of the Portland, Oregon-Vancouver, Washington area and the upper river beyond. Arriving to the Portland-Vancouver area brings you to the end of the lower river area. The cities of Portland and Vancouver represent the largest metropolitan area on the whole river. Vancouver’s waterfront is mostly commercial and has no marinas or services. About two miles before arriving in the Vancouver area and just as you encounter the first container ship terminals of Portland is the Willamette River. The Willamette River is a major tributary to the Columbia River. It extends almost two hundred miles south through central Oregon between the Coast and Cascade mountain ranges.

Downtown Portland lies approximately eleven miles upriver. There is only one marina located in the downtown Portland area, Columbia Crossings River Place. Hayden Island, located adjacent to Interstate 5 on the Portland side of the river, is the unofficial epicenter of marine activity. Several large marinas, fuel docks, a boatyard, and the Columbia River Yacht Club are located here.

According to known geologic history, a large landslide occurred on the river between the lava cliffs of Table Mountain and the north wall of the Columbia Gorge, approximately 35 miles east of where Portland is today. Sometime between 1100 and 1250 A.D., the slide dammed the river, which rose between 200’ and 300’ above sea level. This natural dam created an inland sea that extended from Oregon and Washington into Idaho. This natural bridge or dam collapsed sometime during the 1690s, which coincides with the last Great Cascade Subduction Zone earthquake. This collapse created the famous Cascade Rapids near Stevenson, Washington.

Lewis and Clark would first write of the Cascade Rapids in 1805. Settlers had to portage around them, for they represented a barrier to all who travelled up or down the river. In 1864, a small railway was built to move people and goods around the rapids and in 1896, a set of locks were completed to move boat traffic past this natural barrier in the river. The city of Cascade Locks was born.

The defining feature of the upper Columbia River are the series of hydroelectric and irrigation dams that have basically redefined the river itself. The first was the Bonneville Hydroelectric Dam completed in 1938, located approximately 30 miles east of Portland. The reservoir created by the Bonneville Dam covered the Cascade Rapids and the locks that were built to circumnavigate them. The subsequent dams that were built turned the upper Columbia and the lower Snake rivers into a series of lakes.

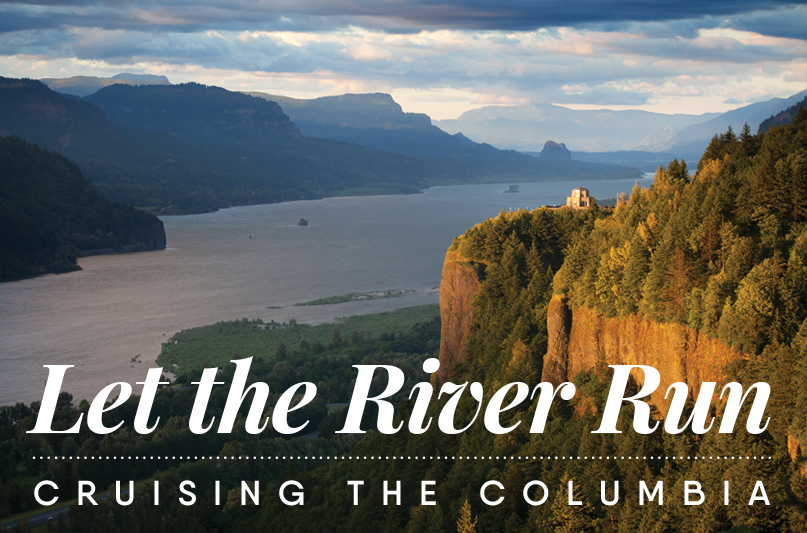

The upper Columbia River can be divided into two areas: the Columbia River Gorge (the Gorge) and the area east of the Gorge. The Gorge is where the river cuts through the Cascade Mountain range and is known for its consistent high winds. For that reason, it has been extremely popular for years now with sailboarders and wind surfers. The high winds conversely can make it challenging to the average boater.

The Gorge basically runs from the Bonneville Dam, past the town of Hood River, Oregon, to The Dalles and The Dalles Dam. The town of Hood River is also where the only decent marina and fuel can be found for the entire upper river area. The next fuel stop is not until the town of Umatilla, Oregon, about 20 miles before you get to the mouth of the Snake River and the Tri-Cities area.

Beyond the city of The Dalles and The Dalles Dam, the river can be characterized by calm winds and hot temperatures in the summer, perfect for water-based activities. For the very adventurous, one can get as far as Lewiston, Idaho, up the Snake River. The first four dams on the Columbia and the first four on the Snake sport locks to navigate.

In researching this article, I learned that for this area, the holy grail of boating is to run as far up as Lewiston Idaho, on the Snake River. The Snake River is the largest tributary to the Columbia River. At 1,078 miles in length, its head waters start in Yellowstone Park. The river’s mouth is located near the Tri-Cities area in Washington. Even though the Snake is over one thousand miles long, only the first 141 miles to Lewiston can be safely navigated. In the ‘60s and ‘70s, the Army Corps of Engineers constructed four dams with locks between the Columbia and Lewiston creating a series of reservoirs and covering some sixty sets of rapids that hindered boating and shipping up to that time.

One thing that needs to be said about this entire area is that moorage and fuel is very limited on the upper river. Careful planning and boat preparation need to be done for each night’s stop, fueling up, and transiting the locks (i.e. plenty of fenders and lines).

Venturing beyond Portland on the Columbia River shouldn’t be considered until extensive planning and research go into the trip. The Oregon State Marine Board is a good place to start. They also produce an informative book that can be invaluable (website at oregon.gov/osmb). The next resource should be the Columbia River Army Corps of Engineers website (nwd.usace.army.mil). In addition to detailed information and photos of each dam, there is a schedule for the locks. They have synched up the schedule for each of the locks to make it easier for boaters.

Of course, close study of a good chart is a must. Another great secondary resource that I have used for many years now is the satellite view on Google maps. Anytime I have booked trips into places and marinas that I am unfamiliar with, I will pull up the satellite view to get a look at where I am going.

There is one last element that needs to be mentioned, and that is weather. Even though the Columbia River is a marine environment, it is also inland. The weather models that the usual weather sites use do not accurately forecast inland winds. The National Weather Service office in Portland, Oregon, is the source that should be consulted for forecast weather conditions for the Columbia River (weather.gov/pqr).

As always, wherever you decide to go cruising proper maintenance, planning, and smart decision making are the keys to a good boating experience. Cruising up the Columbia River is a uniquely Pacific Northwest experience, a slice of that Lewis and Clark spirit set across Washington and Oregon’s dramatic coastline all the way to the Wild West of the interior. If you’ve got the itch, do your homework, be safe, and go for it.

Read the full story on Issuu