Then the world turned upside down.

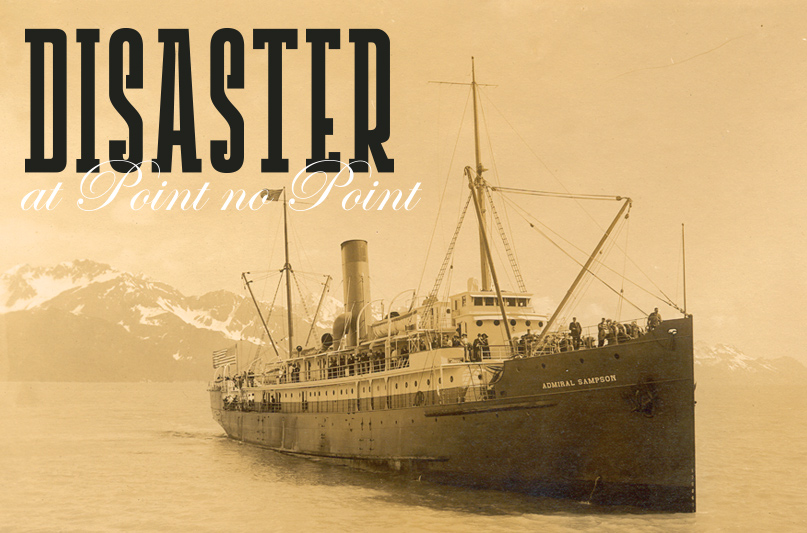

The steamship Admiral Sampson departed Seattle at 0400 hours that morning en route to Juneau with 160 crew and passengers aboard. Visibility was poor because of dense fog and smoke from area forest fires. Captain Zimro S. Moore ordered extra lookouts and the ship’s speed to be reduced to 3 knots. Somewhere near Hansville, Washington, Point No Point laid abeam the Admiral Sampson’s port side. The light station’s engine-powered fog signal could be heard, but the pea soup that enveloped the channel seemed ominous.

The steamship Admiral Sampson departed Seattle at 0400 hours that morning en route to Juneau with 160 crew and passengers aboard. Visibility was poor because of dense fog and smoke from area forest fires. Captain Zimro S. Moore ordered extra lookouts and the ship’s speed to be reduced to 3 knots. Somewhere near Hansville, Washington, Point No Point laid abeam the Admiral Sampson’s port side. The light station’s engine-powered fog signal could be heard, but the pea soup that enveloped the channel seemed ominous.

“I feared something was wrong, so [I] arose and peeked out,” Buor said of the ship’s whistles, in an account published later that day in the Seattle Star newspaper. “It was fearfully foggy, but the steamer was still moving, so I concluded everything was all right and climbed back to my berth. Hardly was I back when I heard and felt a terrible crash.”

The 300-foot steamship Princess Victoria, en route from Vancouver to Seattle, rammed into the Admiral Sampson (a slightly smaller steamship at 280’) opposite the No. 2 hatch astern of amidships.

All hands—officers, crew and passengers—on both ships acted swiftly. The Princess Victoria and Admiral Sampson’s wireless telegraph operators sent out SOS messages; in response, the steamship Admiral Watson reported that it was off West Point Light Station in Seattle and on its way to render assistance. Princess Victoria’s captain, Patrick J. Hickey, kept his ship’s speed at slow ahead to hold her prow in the gash in the Admiral Sampson’s side while lifeboats were lowered and his ship took on passengers.

Women were lifted from the Admiral Sampson’s deck onto the Princess Victoria, and men jumped overboard and swam to lifeboats. Admiral Sampson passenger Joe Brosman, one of about 20 ironworkers headed to Juneau for work, found two children in their nightclothes, clinging to an older woman on the Admiral Sampson’s deck. “He carried them, one by one, the children first, and hoisted them aboard the Princess Victoria,” the Seattle Star reported.

Another ironworker, J.H. Varley, told the Seattle Star: “The bow of the Princess towered high over the deck of the Sampson, and we were helping the crew of the Princess hoist passengers to her deck. By and by, when all the women near had been lifted up to the Princess Victoria, we men climbed aboard. We were none too soon, for the Sampson turned her nose down into the water and made as pretty a dive as you ever saw. There wasn’t any splash to speak of. Were none too soon…”

Fire from a ruptured oil tank aboard the Admiral Sampson forced the Princess Victoria to back away, and seawater flooded the disabled ship. At 0602 hours, the Princess Victoria’s wireless telegraph operator reported of the Admiral Sampson: “She has sunk.”

The Admiral Sampson descended below the surface stern first and came to rest on the sea floor at a depth of 320’. Three passengers and eight crew members, including Captain Moore, went down with the ship. Ezra Byrne, the Admiral Sampson’s assistant engineer, was badly injured in the fire and later died at Providence Hospital in Seattle.

Tragic, indeed, but that so many lives were saved in such a short time — 114 of 126 people aboard the Admiral Sampson were aboard the Princess Victoria or lifeboats within 17 minutes of the collision — points to the training, focus and quick action of all hands.

“Captain Moore took charge of the rescue work with unusual skill and dispatch,” the Seattle Star reported. “Boats were promptly lowered and ropes thrown out. The last seen of Captain Moore was just as [his ship] sank. He was raising his hand as though in token of farewell. As the bow of the ship dipped into the water, he was swallowed up.”

At his side was Walter E. Reker, the Admiral Sampson’s wireless telegraph operator, who “stayed at his post until his calls were finished, even though the wireless operator on the less damaged Princess Victoria assured him that he would handle the calls for assistance,” Betty Lou Gaeng wrote in a 2011 story for The Sounder, the publication of the Sno-Isle Genealogical Society.

“After completing his own SOS calls, Reker then assisted passengers into the lifeboats. As the last, loaded boat left, he reported to Captain Moore on the bridge. Standing side by side, they went down with the ship.”

Reker was 20 years old, his captain 50.

A crowd gathered at the wharf at Seattle as the Princess Victoria arrived with survivors shortly after 1000 hours. “Her decks were crowded with people, half of them well-dressed and the other half with only fragments of clothing protecting them from the cold,” the Seattle Star reported.

“A gaping wound loomed large in the vessel’s bow, only two or three feet above the water line … In the breech hung a battered hatch cover from the Admiral Sampson.”

U.S. District Court records state that three passengers and eight crew members went down with the ship. Passengers included Ruby Whitson Banbury, who had married the previous year; George Bryant, a printer headed to Alaska to seek employment; and John McLaughlin, who was last seen clinging to the ship’s rigging as the Admiral Sampson sank.

Those who perished included ship’s cook L. Cabanas, who was raising four young children on his own after his wife’s death two years earlier; Scottish-born stewardess Mary Campbell, who was on her first voyage on Admiral Sampson; quartermaster C. M. Marquist; Captain Zimro S. Moore; chief engineer Allen J. Noon, who reportedly drowned while trying to save Mrs. Banbury; wireless telegraph operator Walter E. Reker; watchman A. Sater; and messboy John G. Williams.

Pacific-Alaska Navigation Co., owner of the Admiral Sampson, was quick to blame the Princess Victoria for the collision, alleging the ship had been traveling at too great a speed for the visibility conditions. Canadian Pacific Railway, owner of the Princess Victoria, was equally quick to sue Pacific-Alaska Navigation Co. for libel, claiming damages of $670,000. The ships’ owners later agreed that the collision was the result of “mutual fault” and that the U.S. District Court should determine loss claims.

In 1917, U.S. District Court Judge Jeremiah Neterer awarded $17,509 to Pacific-Alaska Navigation Co., and Canadian Pacific Railway received $16,065—roughly $335,000 and $307,000, respectively, in 2017 dollars.

Tributes came in for the captains and crew of both ships. The Seattle Star editorialized on its front page that lives were saved by “the coolness with which the passengers faced their peril” and the “coolness and the courage and discipline of the crew of the Sampson.”

The Seattle Star also gave credit to Capt. P.J. Hickey of the Princess Victoria. “He kept the prow of the Victoria in the hole torn by his ship in the Sampson’s hull. This gave the passengers and crew the chance to save themselves.”

The Railway and Marine News reported in its September 1914 edition: “The sad event cast a gloom over shipping circles generally, owing to the fact that both steamships and all of the officers concerned were so well known, Capt. Moore particularly, being a lifelong sailor and one of the pioneer skippers of the Northwest and Alaska, a popular man in every way and an able commander.”

The publication editorialized in the same edition that Moore was “one of the best loved steamship men in that service … He has commanded many vessels in Alaskan waters and was known to all as a capable, kindly officer.” The publication predicted that “legions” of mariners would, “when passing the spot where he went down to his grave, offer a silent prayer to a hero and a gentleman who met his fate as becomes the true master mariner.”

Reker’s name was added to the Wireless Operators Memorial in New York City’s Battery Park. His name is near that of Jack Phillips, who died from exposure after the sinking of the RMS Titanic.

The Wireless World reported in April 1915: “As the cargo of his vessel consisted of oil, the horrors of fire were super-added to the situation and Reker found too much work to do to think of his own safety. He shared the fate of the captain side by side with him on the bridge.”

Telegraph and Telephone Age reported on May 16, 1915: “It is proof of the bravery and efficiency of the crew that [most] passengers were saved. Reker might have saved himself by taking to the boats with the passengers and the greater part of the crew. He remained at the wireless telegraph key, however, giving direction to the rescuing ship which proved invaluable. He ignored repeated appeals from the boats to save himself. When the last boat had left safely, Reker reported to the bridge and remained to share the fate of the captain. It proved to be too late for them to leave and eight of the men, including the wireless telegraph operator, went down with the ship.”

The SS Admiral Sampson was built in 1898 in Philadelphia for the American Mail Steamship Company and named for Rear Adm. William T. Sampson (1840 to 1902), who led U.S. naval forces to victory in the Battle of Santiago de Cuba during the Spanish–American War.

The Admiral Sampson measured 280’, with a beam of 36.1’ and gross tonnage of 2,262. Its hull was constructed of steel and its two upper decks wood, and the ship featured a single smokestack. Its twin propellers were powered by 2,500-hp engines.

The ship made regular trips between Philadelphia and Caribbean ports until 1909, when it was purchased by the Alaska Pacific Steamship Company and began plying the San Francisco-Puget Sound shipping route. Alaska Pacific Steamship Company merged with Alaska Coast Company in 1912 and became Pacific-Alaska Navigation Company. The new company also acquired the Admiral Sampson’s sister ships, and the fleet offered freight and passenger service between San Francisco, Puget Sound, and Alaska.

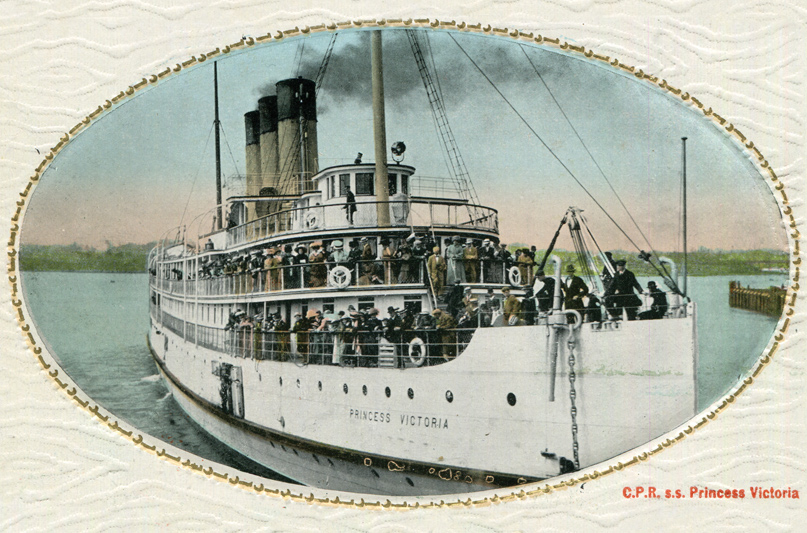

The SS Princess Victoria was built in England in 1902. “The Canadian Pacific Railway, already operating the fastest and handsomest ocean steamships in service from the Northwest, introduced a new standard of speed and elegance to Puget Sound with the arrival of the splendid three-funnel steel steamship Princess Victoria from the yards of Swan & Hunter, Newcastle,” evergreenfleet.com reported.

“A twin-screw steamer of 1,943 tons, 300 x 40.5 x 15.4, her triple expansion engines of 6,000 horsepower gave her a top speed of 20 knots. She had accommodations for 1,000 day passengers and 152 overnight passengers in 76 staterooms.”

Princess Victoria was repaired after the collision and continued as a passenger ship. In 1930, it was rebuilt and widened 18’ to accommodate 60 automobiles. In 1952, Princess Victoria was retired and sold to Tahsis and Co., which converted it to a barge. In 1953, it struck a rock and sank in Welcome Pass, between Thormanby Island and British Columbia’s Sunshine Coast. The engine room telegraph and steering were recovered and repurposed for the M/V Uchuck III, which still sails today.

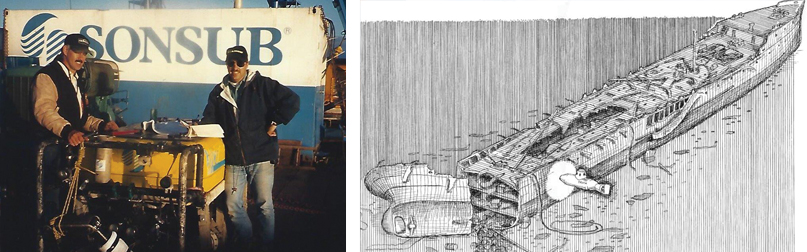

Using side-scan sonar, dive explorers Gary Severson and Kent Barnard located the Admiral Sampson’s final resting place in 1991, and over the next year obtained exclusive salvage rights. In 1994, a research vessel perched over the site and the men climbed into a two-man sub and began their slow descent to the wreckage. They would be the first to see the ship in 80 years.

At that depth, visibility was poor and the current strong, Severson recalled in a July 18, 2018 interview. “We were bouncing along, and then we saw this huge wall of white,” he said. It was the Admiral Sampson’s bow, covered in sea anemones.

“The ship lay in two pieces, having buckled at its weak point and broke apart as it sank or after it hit bottom,” Severson said. The ship’s wood superstructure had collapsed. The ship had become occupied by ling cod, octopus, ratfish, yellow eye, and various other denizens of the deep.

Severson looked unsuccessfully for the ship’s safe, which he said would have contained its payroll and passengers’ valuables. But the mission did recover numerous other artifacts, including the ship’s whistle, engine order telegraph, and galley items.

The collision was a grim reminder of the importance of the Point No Point Light Station, which was established in 1880 to provide a navigation aid to ships traveling to and from the growing port cities of Seattle and Tacoma. But even the lighthouse and its engine-powered fog signal were no match for the thick cloud that enveloped the entrance to Puget Sound that day.

“We have a place at Point No Point and when it gets foggy, the visibility is bad,” Severson said. “I was out on a boat in the fog there once. It was so thick it was terrifying.”

Wisely, modern Washington state ferry captains on the nearby Port Townsend-Coupeville route will cancel runs and wait for the fog to clear rather than risk it.

Read the full story on Issuu