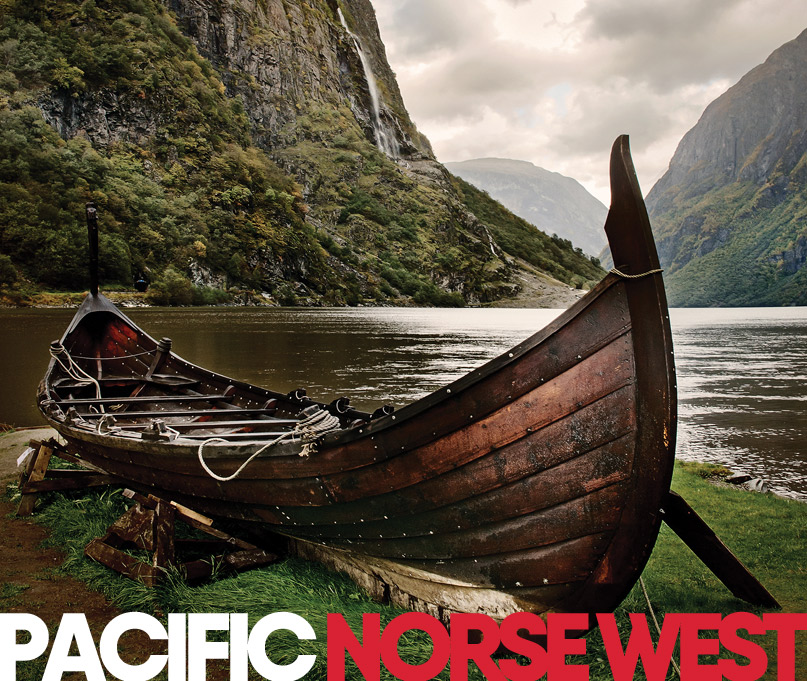

The night was young and the seas foul on January 2, 1903, as the Norwegian-flagged barque Prince Arthur made course from Valparaiso, Chile, to Esquimalt, British Columbia, when disaster struck on the Washington shore. Reportedly, shipmaster Hans Markussen, a lifelong mariner, discerned the outline of the brooding Olympic Peninsula shoreline in the lightening fog minutes before tragedy.

The night was young and the seas foul on January 2, 1903, as the Norwegian-flagged barque Prince Arthur made course from Valparaiso, Chile, to Esquimalt, British Columbia, when disaster struck on the Washington shore. Reportedly, shipmaster Hans Markussen, a lifelong mariner, discerned the outline of the brooding Olympic Peninsula shoreline in the lightening fog minutes before tragedy.

“Sving! Kom deg ut herfra!” (Turn! Get out of here!) Markussen may have called to the crew, but to no avail. The ship struck bottom, part of a brutal reef and rocky pinnacle system that lies north and east of Carroll and Jagged islands, far from civilization. Her metal hull was immediately punctured and snagged by a reef off Kayostia Beach. The terrified crew hoped that a flood tide could free the ship as they desperately made repairs. But the waves built higher and the winds grew stronger. Ultimately, the ship was ripped in two by the waves, and only the aft section remained on the reef. The 20-man crew was sucked into the brine, 18 hands lost.

The two survivors, Christopher Schjodt Hansen (second mate) and Knud Larsen (sailmaker/carpenter) washed ashore where they were helped by local homesteaders and Native Americans. The homesteaders? The brothers Iver, Ole, and Tron Birkestol, fellow Norwegians who found their way to the Pacific Northwest by more peaceful means. Did the survivors and the rescuers speak their common tongue when they met in the American rainforest, maybe with a greeting of “Hvordan går det?” (“How are you?”).

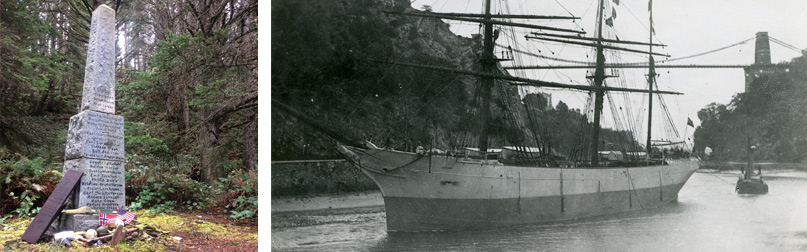

Not only were the two Norwegian survivors and their rescuers fellow countrymen, but the Norse Club of Seattle and the Norwegian consul and vice consul were quickly on the scene. Vowing that the Norwegian mariners lost at sea would not be forgotten, an ambitious plan was enacted to erect a solid granite monument at the scene of the wreck at Kayostia Beach on the Olympic Peninsula.

With a stubbornness and resourcefulness often associated with Norwegians, a 10’ tall granite tribute complete with 5’ obelisk was shipped and lugged through the rainforest to the rugged coastline that doomed the Prince Arthur.

In 1904, the Norse Club of Seattle erected the monument and representatives of the local Norwegian community held a dedication ceremony. Ever since, pilgrimages are made to the site to pay homage and clear debris to maintain the site. Due to its protected status within the Olympic National Park, enacted years after the monument’s installation, a highway will never reach it. Instead, trekkers face a rugged coastal hike over tidelands.

The Prince Arthur is but one connection Norway has to the Pacific Northwest and our maritime scene. According to the Norwegian-American Historical Association (NAHA), more than 800,000 Norwegians immigrated to North America between 1825 and 1925, and roughly one-third of the country’s population ended up in the United States. According to the same source, this means that no country, except Ireland, contributed a larger percentage of its population to the United States than Norway. In the Pacific Northwest, many of these immigrants were drawn to the lumber and fishing industries where they made their marks.

One of the notable chapters of this history is the formation of Foss Maritime, founded by Norwegian immigrants to Tacoma, Washington, and still a major player in the regional marine transportation industry. The story is the stuff of legends. In the summer of 1889, Norwegian immigrant and new bride Thea Foss bought a rowboat from a burnt-out fisherman for $5. Foss sold that boat for $15 and bought two more boats and started renting out her fleet for 50 cents a day. Her husband, Andrew Foss (a carpenter), returned from a completed project to his savvy wife and a growing business.

What started as the Foss Launch Company grew and evolved over the decades into the primarily tugboat company we know today, Foss Maritime. You can see some of the company’s iconic early builds, like the Arthur Foss tugboat, at the Seaport Museum in Tacoma, Washington. The Thea Foss Waterway in Tacoma is an immortal homage to the legacy.

When one looks at the Arthur Foss, one notices classic design features that hearken back to the mother country. Notably, the rounded transom is a clear sign of Norwegian/Nordic influence. This double-ender or canoe stern style also spread into Pacific Northwest yacht design, notably with local builder and legend Bob Perry’s game-changing Valiant 40 sailboat (and her many evolutions). Although canoe stern styles are harder to find with modern production builds, largely because they eat up valuable stowage space and make water access over the transom to giant swim steps difficult, they will always look gorgeous and are yet another example of Norwegian culture seeping into the Pacific Northwest.

I had a personal experience aboard one such Norwegian-inspired working vessel during a brief stint as a commercial albacore tuna fisherman out of Westport, Washington. Captained by Kurt Little, the F/V Anchor is an all-wood, clearly Scandinavian-inspired commercial trolling vessel in immaculate shape that is still working the season alongside the tricked-out modern crews.

“The Anchor was originally owned by the guy who taught me how to fish when I was just getting started—Captain Sig,” Captain Little told me. Sigurd was, you guessed it, a Norwegian immigrant fisherman.

can attest as a deckhand that the canoe-style transom was both beautiful and a bit hard to haul fighting tuna over. Sig and Kurt even took the Anchor to Midway one season, not bad for an all-wood boat less than 50’ that could’ve been built around WWI. If you find yourself off the coast of Washington or Oregon this summer or fall and you see a white and red, all-wood fishing classic trolling by, you may just be looking at the Anchor, another local living tribute to Norway. She is often moored in Fisherman’s Terminal during the off-season.

The influence of Norwegian immigrants is not just found on the water in the form of boats and business. Some of the area’s most charming coastal and boat friendly communities have their roots in immigrant neighborhoods, and many of these towns still fly Norwegian flags and embrace the theme. Charming small-town Poulsbo, Washington, a popular boating destination in central Puget Sound, is one such example.

Even in the heart of the Seattle metropolis, the Ballard neighborhood near the Locks has a proud maritime industry with deep roots to Norway. Ballard even hosts perhaps the largest Syttende Mai (May 17) parade in the country. May 17 is known as Norwegian Independence Day and is equivalent to America’s Fourth of July or Canada Day (July 1) in terms of national importance. Bergen Square in Ballard is named after the Norwegian city, and a statue of Leif Erickson, the true first European to set foot in America, stands tall in Shilshole Bay Marina in Seattle, where he symbolically looks west out over the water. If one boats farther north, Petersburg, Alaska, has a similar feel and charm as Poulsbo. All these places have deep ties to Norway and the sea, much to the benefit of boaters and boating culture.

How do I know all this? Well, I am a Norwegian-American and I decided to visit the Kayostia Beach monument myself, in January no less. From one of the nearest trailheads at Rialto Beach, I had to time the tides just right and maintain a lively pace over slippery rock fields and scramble up towering headlands, sometimes with a helpful anchored rope that’s part of the trail system. Occasionally, running was necessary to nip around a cape that the rising tide threatened to submerge. The weather was striking; for one hour I’d brace against sideways sleet and heavy winds and fog, and the next I’d hike sweaty and shirtless under a bright sunny sky in 70-degree weather. The immense forested monoliths were majestic in all conditions. Progress was halted at high tide, and I made camp after the first day right above Kayostia Beach on a forested headland.

The nights in the Olympic forest are about as dark as they come due to the dense canopy and near-constant overcast. The nearby Hoh Rainforest, part of Olympic National park, gained national attention thanks to the One Square Inch project run by acoustic ecologist Gordon Hempton. Using scientific metrics, Hempton makes the case that the rainforest is one of, if not the, quietest places on Earth.

This is partly thanks to the acoustic padding of the mosses, quiet fauna, and sheltered geography. Even the rumble of the Pacific was drowned out after a short inland stroll as I made camp. I hadn’t seen a soul since the trailhead and wouldn’t until I left the park. While near complete silence, darkness, and isolation may sound terrifying to some, I was overcome with a feeling of peace. As I went to bed in my camping

hammock, gently swaying on a root knoll above the sea of sword ferns, I felt no fear.

While ghost stories of vengeful sailors abound in nautical lore, the Norwegian hands lost on the Prince Arthur were mourned, honored, and their immortal tribute cared for. I was on a pilgrimage to pay them, and the mighty ocean upon which they made a livelihood, respects. Even for a non-superstitious, science-minded fellow like myself, those thoughts contributed to a good night’s sleep.

The next day was an early rise to make a low tide. A quick scramble down the headland and a brisk jog across the beach took me to the small glen in which the monument stands. I collected my composure before entering the forest, an outdoor cathedral. After a hundred yards or so, I stood before the granite of the Norwegian Memorial. I unloaded my backpack and read aloud the names of the dead. Touchingly, small American and Norwegian flags fluttered at the base, a recent memento offered by another passerby.

A small pile of gifts from hikers ranging from perfect little sea shells to empty cans of beer, no doubt drank with a solemn “Skål”, sat near the two flags. With the distant boom of the waves and the rustling of trees in the wind a gentle song, I gave those Norwegians, the America that took them in, my ancestors, immigrants and refugees everywhere, the Pacific Northwest, and all men and women who go to sea a silent tribute from my heart before rallying for the long slog out of there.

Read the full story on Issuu