As a Native from Kodiak Island, Alaska, I never knew that our ancestors made open skin-boats, angyaat, until the mid-1990s when I started exploring ethnographic museums. The first time I saw an angyaaq (singular form of angyaat in Alutiiq) model was in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), Russia in the spring of 1991. I did not believe this boat was from my region because every elder I had ever spoken to never mentioned that we once had boats like that. We only had kayaks.

As a Native from Kodiak Island, Alaska, I never knew that our ancestors made open skin-boats, angyaat, until the mid-1990s when I started exploring ethnographic museums. The first time I saw an angyaaq (singular form of angyaat in Alutiiq) model was in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), Russia in the spring of 1991. I did not believe this boat was from my region because every elder I had ever spoken to never mentioned that we once had boats like that. We only had kayaks.

Angyaat, open skin-boats, were commonly seen in the Gulf of Alaska prior to European and Russian contact. The boats would traditionally have a wood frame tied together with sinew, rawhide, and roots, and covered with sea lion skins sewn together using a watertight stitch. By the 1860s, they disappeared from use and would not be seen again for over a century in this region. The first European images of angyaat were drawn by John Webber during Captain Cook’s third and final expedition to the Prince William Sound region in the spring of 1778. In fact, his drawings are some of the only known illustrations of these boats to exist from this time.

My interest in these boats was piqued when the drawings were revealed to be from our region. I became interested in the cultural significance of the boat’s bulbous bow and historical implications for why they had disappeared.

Looking at the history of Russian contact, the angyaat could haul entire families and communities and get away from danger quickly. The Russians did not want this to happen, so they took the boats for themselves and used the angyaat until the 1860s, when Americans came in with a solid wooden skiff that replaced the angyaat entirely.

Over the last 20 years I have personally examined 14 angyaat located in Russia, Germany, France, England, and the United States. This spring, I just learned about one more model angyaaq in an English collection that was misidentified, as most of the others were. With only 15 genuine builds in museum collections scattered across the world, and none in Alaska, it feels urgent to bring this knowledge home while we still have elders who remember the traditional methods of construction and wood preparation.

The University of Washington’s (UW) Burke Museum happens to have one of the 15 model angyaat that exist in the world. When I started working at the UW and Burke Museum in 2013, I took the opportunity to research and see if we could reintroduce the angyaaq to the communities on Kodiak Island by building models.

In the spring of 2014, I sketched, photographed, and created a 3-D photogrammetry of the boat. Then I made a to-scale miniature model of the Burke Museum artifact to see how hard it would be to replicate the angyaaq. After figuring out the dimensions, I created 15 kits and took them to Kodiak, where I had been collaborating with the community of Akhiok for the past 17 years. We worked with elders, teachers, adults, and youth to make these models at the Akhiok Kids Camp. We completed 13 builds during the 2014 camp, sparking a desire in many to try and construct a full-sized, functional angyaaq.

How we were going to do this was beyond me at that time, for I never had taken on such a task. But we had just made 13 models based on an original model, so it seemed possible to make one that was full-sized.

In the fall of 2014, I got the word out that we were going to try and construct a full-sized angyaaq. In the spring, I started gathering wood and materials for the boat project. I reached out to another individual who constructed a similar vessel but never received a response. I roped in a fellow archaeological colleague, Dr. Peter Lape, to help in this crazy endeavor.

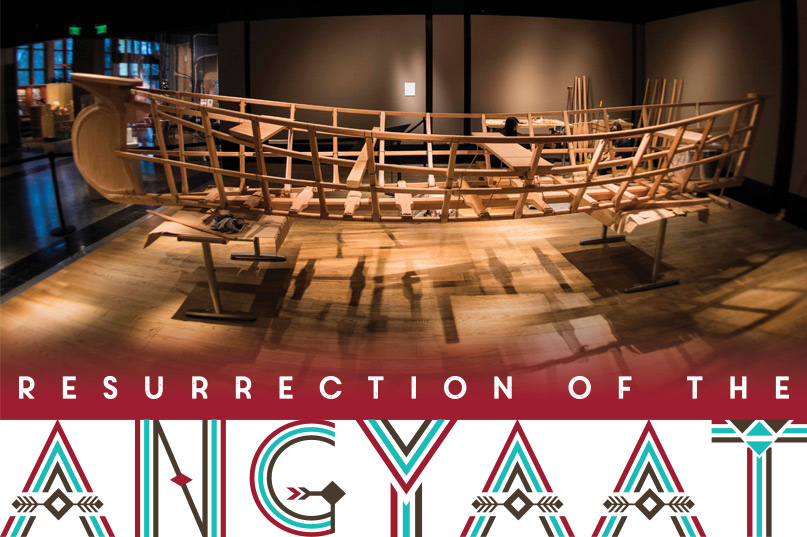

Over the next nine months, we received donations of fabric from George Dyson and wood from Jensen Motor Boat Company, and funding from the Sea Alaska Corporation and Friends of Native Art. With help from Brian Johnson, Burke Museum staff members, UW students, deans, professors, and many more, we started constructing a frame at the beginning of June. One UW student in particular, Rosemary Mathison, volunteered her time to help us. She ended up working with us for over two years. We constructed a 27′ frame in two weeks and then we dismantled it so we could store the incomplete boat until we could finish it.

Taking what I learned from this experience, I prepared my return to Akhiok where I would work with the community and attempt this same effort, with just five days to do what previously took us two weeks. In August of 2015, I returned to Kodiak with Rosemary to attempt the impossible.

I say impossible because we had to find wood from the surrounding beaches large enough for the bow and stern, and handsaw all the other parts from spruce lumber from the city of Kodiak, which we brought with us in the chartered plane to the village. The camp is located at the southern end of Kodiak Island at Cape Alitak and is a 45-minute skiff ride from the village of Akhiok. Everything needed to be skiffed in, including water and tents, and camp set-up often takes a full day.

On the fifth and final day of camp, we zip tied the frame together with only six of us remaining in camp. What a relief! But we still had a lot more work in the following year before we were even near completing it. It was amazing that we constructed two frames in 2015, one at the Burke Museum and one at the village of Akhiok.

About our collection:

The Burke Museum cares for over 16 million objects with focuses on culture, biology, paleontology, and geology. I work in the Ethnology Department where we care for over 50,000 ethnographic pieces. The museum has collections from North and South America, the Pacific Islands, Asia, Australia, New Zealand, Indonesia, Russia, Japan, and China.

Part of the collection consists of full-sized vessels from these regions that have been donated to the museum since it was founded: tribal canoes, a Chinese river boat, umiak, outriggers, a Balinese Jukung , and double outrigger. Each one represents a distinct culture and has knowledge embodied in it that can teach us about the boat construction, use and history.

About our Work:

The angyaaq from the story is now part of our ongoing collection and sharing of traditional knowledge with tribes. We are responsible for caring for, maintaining, and sharing these vessels, whose traditional construction methods are threatened by limited access to original materials and global economics. Small traditional vessels are being replaced with contemporary vessels made out of imported materials that are often cheaper and faster to construct. The Burke plays an important role in keeping this knowledge alive.

So far, we have worked with a Balinese boat builder and the Sugpiat, Tlingit, Haida, Nooksack, Suquamish, Duwamish, Calispell, and Yakama Tribes in learning about their vessels. We have only started to ripple the water of knowledge and hope that this will raise an awareness of how important it is for us to not only care for the boats, but help others keep their traditional boating practices alive within their communities.

Visit: BurkeMuseum.org

Our next goal was to reassemble, tie, and cover that first angyaaq at the Burke. In December 2015, we were given exhibit space to finish the angyaaq we started in June. A group came together at the Burke and we spent two weeks tying, sanding, carving, sewing, and covering the angyaaq. For the first time in over 155 years this unique vessel, designed and used by my Kodiak community, was constructed.

To have been part of this process was humbling because I learned more and more about the technological knowledge embodied within the boat and was amazed that we nearly lost this knowledge. The bulbous bow, for example, now seen on many oceangoing vessels, was part of this boat’s original design from the start.

To learn that the function of this bow design increases the boat speed and decreases the energy costs made me pause because my entire life we were told all our past ways of life were primitive and worthless. How is a design like this worthless when it was far more advanced than some of our current hull designs?

We have been taught to label things that Native peoples create as being primitive, yet this design would never be considered primitive if the advanced knowledge and thought put into the construction and function of this boat was understood. I am curious what else is dismissed because we label things from the past as being primitive. I digress. After completion of the angyaaq, it joined other vessels at the Burke that hail from across the Pacific and are now being examined with a new perspective.

We happened to launch our angyaaq on Seattle’s Opening Day of the 2016 boating season. It was wonderful because we did something that seemed impossible to do, and more importantly, we helped reintroduced the Sugpiat/Alutiiq boat back into the world. The Burke Museum is the first to have a fully functioning angyaaq in its collection.

We returned to Akhiok the summer of 2016 and finished the angyaaq we started. This time we were not so afraid to make mistakes, because we learned through the process that mistakescan teach us. However, we are not stopping here because our ultimate ambition is larger. We want to help communities take back the knowledge lost because of change brought in by outsiders. We are reversing the tides of this loss. Communities are increasingly learning about their traditional ways of living and using them once again.