I was high on life as Bainbridge Island’s newest sailor during the sweltering, wildfire-themed summer of 2015. Sick of Florida, where I had lived my last college semesters and some change aboard a beat-up Catalina 27 (1973), I had purchased one of the few remaining Pacific Northwest-based Albin Vega sailboats sight unseen over the internet for a screaming deal (a divorce was in the seller’s calculations somewhere). The exploits of young explorers on a budget like Norwegian Jarle Andhøy and American Matt Rutherford had clearly left their mark on me.

I was high on life as Bainbridge Island’s newest sailor during the sweltering, wildfire-themed summer of 2015. Sick of Florida, where I had lived my last college semesters and some change aboard a beat-up Catalina 27 (1973), I had purchased one of the few remaining Pacific Northwest-based Albin Vega sailboats sight unseen over the internet for a screaming deal (a divorce was in the seller’s calculations somewhere). The exploits of young explorers on a budget like Norwegian Jarle Andhøy and American Matt Rutherford had clearly left their mark on me.

Starting at the white beaches of St. Petersburg, I loaded up my 2003 Hyundai Accent with my meager post-college possessions, strapped my bike to the rack, and floored it across this great country through Baton Rouge swampland, green Texan spring, Rocky Mountain snow flurries, and finally, the most beautiful of them all, Winslow Wharf Marina. When I finally had my first alone time with my new purchase, Huldra, the euphoria took second seat to my curiosity. What goodies had I inherited?

I was relieved to find the essentials and some pleasant surprises, like non-expired flares. The owner had wisely taken whatever toolbox probably lived aboard, bad news for me, but human. Notably, there was a lack of a dinghy. To accomplish all the Pacific Northwest sailing fantasies I dreamed of, I knew I was going to need a good one.

That evening as I made my rounds to the neighbors, an old duffer and I hit it off. Turns out, he had a dinghy, a venerable Avon that he was trying to get rid of for $200. Flushed with hubris, I bought it on the spot and virtually ran back to my boat to take it for a test spin.

After exhausting myself with the old foot pump, assembling the faded wood oars, weaseling in the hardwood floorboard inserts, and straining to deploy the cumbersome thing over Huldra’s generous freeboard, I realized there was no hard transom for an outboard bracket on the Avon. Of course, there was a small leak that I spent some time hunting for and patching. I also realized, if I was serious about cruising, this was a lot of dinghy for one person to handle. The scenarios ran through my head, and unless I was in still seas with only a short distance to travel, my options were limited. No zippy inlet exploration for me.

Although I didn’t regret my purchase and went on to use my Avon often, I quietly vowed to do a better job next time with my dinghy purchase. I offer the following input not as an enlightened guru, but rather as a fellow boater who has learned a thing or two the hard way.

Before you charge into the nearest dinghy supply store and promptly get overwhelmed, I recommend that you spare some moments of self-reflection. Think about not just what you want, but what can you do? What kind of platform is your boat? If you’ve got high freeboard and a bad back, you should think twice about a set-up that involves heavy lifting. Does this mean you go more minimalist, or do you go bigger with a davit system?

What kind of seas do you regularly take on? Seaworthiness in a tender can be vital for those taking on the alluring waters of the north.

This initial step of self-reflection is important to ground yourself in the reality of your situation. Know who you are, what your boat offers, and what your needs are before proceeding.

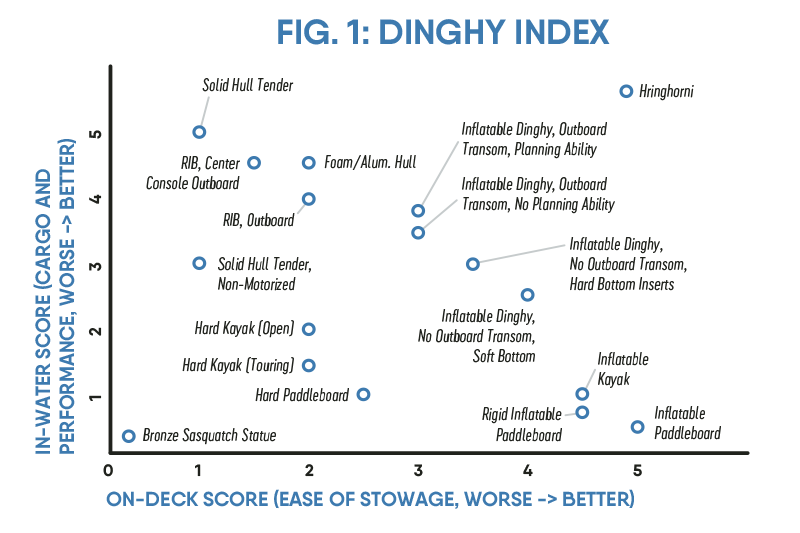

While it can be easy, and even fun, to lose oneself in the dozens of potential questions related to dinghy/tender purchases, it may be easiest to distill the entire thought process down to two fundamental variables: in-water performance and on-deck stowability. Dinghies and tenders are offered in such abundance, you could probably plot the evolutionary tree like the taxonomic one used in biology, and they differ about as much as the kingdoms Animalia and Fungi. Once you address these two variables, you’ve at least determined whether you are animal or mushroom.

Variable 1: In-Water Performance: What do I want and need to do?

Dreamer (Non-Motorized): If you are an avid sailor and/or paddler and are considering a completely non-motorized dinghy route, then first you must fess up and admit that you are an eccentric idealist (who we love).

While a tenable position, the truth is that you have multiplied the factors you must consider as you’ve reduced what you must purchase. If you plan to cruise extensively, trips to shore will involve paddling against the current or sailing upwind, even if all you need is ice for your Old Fashioned from the gas station. Revisit the “Know Thyself” section, meditate a bit, and then proceed.

If you fall into this camp, you still have choices to make. You will probably want something that can move a decent amount of cargo and the occasional passenger at least, and for that there are many inflatables offered that do not feature a built-in hard transom for a mounted outboard. The Avon inflatable from my anecdote falls into this camp, the pros including easy stowage and paddles that disassemble.

If you insist on using kayaks or a paddleboard as your primary tender, then do yourself a favor and get a touring model. Although inept as a cargo/passenger mule, they can at least boast decent seakeeping ability. An inflatable kayak or paddleboard, like the Airis line from locally based company Walker Bay, is probably minimalist incarnate as far as ease of stowability and no motors.

Shore Mule Dinghy (Motorized): It is probably safe to bet that most dinghies fall into this category. Both minimalist and pragmatic, this category’s job is to get maximum people and cargo to and from shore, thanks to a trusty low-horsepower outboard motor and perhaps some maneuvering with a pair of oars.

The choices available in this group can get truly staggering. If we take just one Walker Bay product line as an example, we’re in their Odyssey territory. These boats are completely inflatable, including the floor. They are rated to a recommended 4.5 to 8 horsepower from single short-shaft outboard engines. While you may be able to get dinghies like this on a plane, that’s not their primary purpose in life. These are the putt-putts of the dinghy world, and when paired with a trusty four-stroke outboard, generally enjoy long lives with low maintenance.

To be a shore mule, a dinghy does not necessarily have to be inflatable. Companies like Porta-Bote out of California have been successfully making “origami” tenders for years. These hard-panel boats can assemble and disassemble like large, simple puzzles, essentially giving many of the pros of hard-bottom performance with the pros of inflatable-like stowability.

However, due to the nature of seakeeping, the generally higher cost, and increasing complexity, most hard-bottom dinghies tend to leave the purely “shore mule” category for the glitzier category we’re about to dive into.

Performance Tender (Motorized): With this category, we are no longer in dinghy territory, but rather Tender Town. Generally, the terms dinghy and tender are synonymous, although most consider dinghies to be the smaller, simpler variety, while tenders are proper hard-hulled boats unto themselves. Perhaps dinghies are to boats what tenders are to yachts?

Regardless, the entry level to this world are the rigid-hull inflatable boats (RIBs). This popular tender design features a hard bottom with inflatable gunwales. A British invention, the first RIBs appeared in the 1960s by the Royal National Lifeboat Institution. Offering the performance of proper solid hulls with some of the portability and convenience of inflatables, RIBs remain the go-to tender choices for those who can manage them on deck (we’ll come back to that later).

Also innovative are designs like Bellingham, Washington-based Bullfrog Boats. These tenders have a completely solid hull built of buoyant polyurethane foam incased within strong and lightweight aluminum. Unsinkable in a very literal sense and quite strong, the light construction makes it a bit more manageable on deck.

Right: The shore mule is probably the most common approach,

and bays further from the mooring field become much more accessible with a few sips of gasoline. (Photo: Elsie Hulsizer)

Prominent in the performance tender family is the center console layout. RIBs, Bullfrog Boats, and builders of solid-hull aluminum and fiberglass tenders tend to offer both the traditional mounted-outboard and tiller approach and the center console options that give the tender a “real” helm and nav station. Once we get into the center console realm, the tender category evolves into models that are just as capable as comparably-sized ski boats or runabouts. This bracket also is where things can get very customizable, with some companies offering completely custom builds for larger yachts with specific demands.

Additionally, there are hard-bottomed tenders that are compatible with sail rig packages so the non-motorized dreamers mentioned before can have their cake and eat it too.

In exchange for the capabilities of a “real boat,” these tenders become the most cumbersome to stow aboard. Not only is a large mothership required, but also some kind of hoist, davit system, or jerry-rigged lashing is necessary. Some, usually sailors with less deck space for their length overall, will resort to towing a solid-hull. Whatever the solution is, a general rule is that the larger and more tricked out the tender, the more consideration is needed to stow it safely and conveniently aboard.

Variable 2: On-Deck Stowability: How far will I go to get this thing aboard?

Modern boaters are not the first to dream of owning a large, completely tricked-out boat that is also impossibly easy to stow. The Viking god Baldr was said to have the “greatest of all ships” (according to the ancient Gylfaginning) named Hringhorni that could also fold up into a pocket. The fact that the Vikings fantasized about such a ship in their mythology puts the idea on the plane of the Holy Grail in terms of real-world possibilities.

The on-deck consideration is what grounds many of the decisions made with the on-water goals. Simply put, an aluminum center console with integrated sound system blasting Jimmy Buffet may be the dream, but if you’re at the helm of a 20-something-foot Ranger Tug, you’re probably out of luck. By that same token, that inflatable kayak will roll up nicely to stow aboard, but one should be realistic about what conditions such a dinghy can handle.

In an effort to balance the in-water considerations with the on-deck ones at a glance, I’ve sketched out this chart (Fig.1, above). Several common dinghy/tender types have been given a general, unscientific score from me based upon the two variables mentioned previousily and plotted. The y-axis represents the In-Water Score (cargo carrying and performance abilities) and the x-axis represents the On-Deck Score (ease of stowability). I’m sure the exact scores could be endlessly debated and tweaked around dock talk circles, but hey, we’ve got to start somewhere. Send a letter with your input!

You’ve reflected upon your own abilities and needs. You’ve navigated a few of the fundamental crossroads with your research and know generally where you plan to be on the chart. Now is the time to leave the glowing computer screen and internet research behind to go into the field on a hunt!

I always recommend starting your search at the bulletin boards of marinas and by talking to other boaters who’ve used the dinghies you’re considering. A certain RIB could look great on paper, but somebody whose owned one may have useful bits of information with regards to the on-deck situation.

Additionally, perfectly good dinghies tend to end up as leftovers in garages or boatyards. Those marina bulletin boards can be excellent sources for leads, often for a great price. They can also be good opportunities for first encounters that bring the tender from the product catalogue to life. Internet equivalents like Craigslist can also bear fruit, but generally the listings on a marina bulletin board are a bit more reliable, personable, and bona fide.

In the perfect world, you’d be able to squeeze in a boat show before your big purchase. A big boat show offers excellent in-person exposure to just about everything in the market, with exhibitor experts who are eager to share information and cut a deal. Avoid the impulse purchase but remember those special offers when you collect business cards. If you do end up going with them, the “deal of a lifetime” they offered is worth bringing up again.

Once you’ve chatted to your fellow boaters, scanned the local marina bulletin boards, glanced over Craigslist, and ideally squeezed in a boat show, it’s time to go to your local dealer. At this point in your search, you should be knowledgeable about the subject and know what you’re looking for. This makes you far less susceptible to canned sales pitches and equips you to ask the important questions. If you’re open to a wide variety of inflatables, then you should have plenty of options wherever you go. If you’re after something very specific, you may want to visit the manufacturer’s website to locate the nearest dealer.

This article was made possible in part due to consultation with Steve Guyer of Guyer Boatworks, a Ferndale, Washington-based company. The business specializes in custom-rigged RIB inflatable packages from multiple manufacturers, custom high-end yacht tenders, and davit systems. If interested, feel free to give Guyer a ring for some professional input.

360-647-2628 // guyerboatworks.com

The goal is that once you’re at the store, you’ve got a short list of final candidates and a few very specific questions. The journey will be well worth it, for even a low-end dinghy or good kayak can put you back one or two thousand bucks.

If you are going the high-end custom tender route, you best build a great relationship with the company you’re working with. At this point, you will be shelling out tens of thousands, and you owe it to yourself to get your money’s worth.

The final thought I offer is that there is a very distinct possibility that your well-being will be dependent upon your tender at one point or another during your exciting boating career. A perfect fit between dinghy and skipper is a truly magical thing, and, unless there is a dog aboard, it’ll be your best friend through the best and worst days on the water.