// By Elsie Hulsizer

The Nootka Lighthouse complex stands over Friendly Cove.

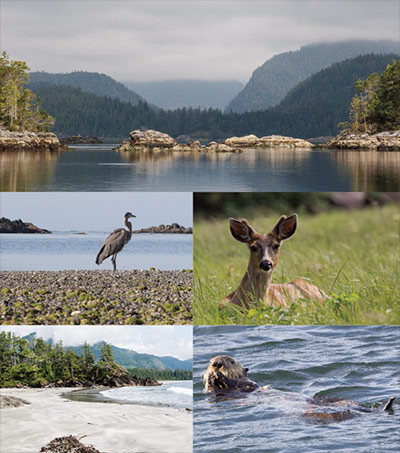

The West Coast of Vancouver Island is a place of contradictions: windy afternoons and calm mornings, rough seas and protected anchorages, rainforests and sunny

summer days.

Although only two or three days by sailboat from Seattle or Vancouver, the West Coast of Vancouver Island can feel almost as remote as Alaska. Much of the coast looks undeveloped and natural, yet it’s still rich in history. It’s only about 60 nautical miles as the crow flies from the marinas, stores, and repair facilities of the populous East Coast of the island, but sailing to the west side requires a full set of spare parts and a blue-water cruising mindset.

These contradictions – and the coast’s attractions – arise from Vancouver Island’s geography: a rockbound exposed West Coast, a backbone of rugged mountains, and a series of sounds and inlets indenting the land. The geography, coupled with attractive small towns and numerous parks, makes the West Coast a Mecca for Northwest cruising boats. It’s an ideal destination for a shakedown cruise before going offshore or to Alaska – or for an adventurous two to three-week vacation.

Getting There

Most guide books about the West Coast of Vancouver Island assume you’ll get there by circumnavigating the island counterclockwise: going north up the island’s east side then south down the west side. Sailors choose this route in the hope that they will have the wind behind them on the exposed West Coast. Power boaters choose the clockwise route to make their rides through ocean swells easier.

A circumnavigation of Vancouver Island can give a feeling of accomplishment and provide a tour of Pacific Northwest cruising grounds, but is a significant undertaking that requires two months or more to do it justice. Wind against current in Johnstone Strait, rough water rounding Cape Scott, and the siren call of warm water in Desolation Sound can leave you with less time than you expected for the West Coast.

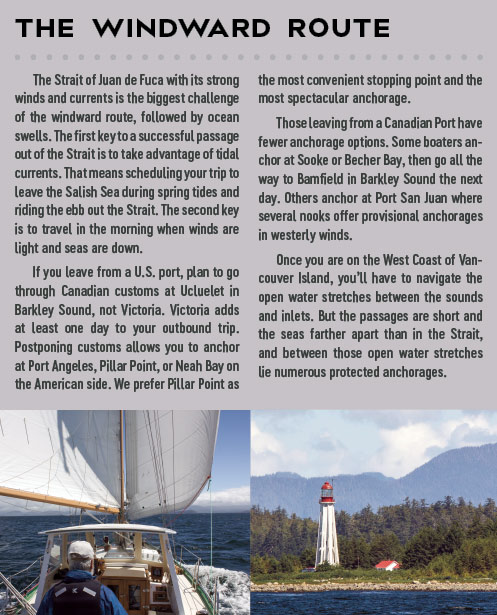

What if you don’t have time for a circumnavigation, or just want to spend more time on the West Coast? Take the windward route: out the Strait of Juan de Fuca, north up the West Coast as far as you can get, then back south down the same coast. My husband Steve and I did that for 18 of our 22 trips on this coast, four in a Chesapeake 32 sloop and the remaining in our Annapolis 44 sloop, Osprey. In two weeks, we could reach Hot Springs Cove in Clayoquot Sound. In three, we could get as far north as Nootka Sound or Esperanza Inlet. On longer trips, Brooks Peninsula was a natural stopping place.

Increasingly, more boats, including powerboats, choose the windward route option. Some even choose to circumnavigate clockwise. Whichever way you go, you’ll find some great adventures.

Increasingly, more boats, including powerboats, choose the windward route option. Some even choose to circumnavigate clockwise. Whichever way you go, you’ll find some great adventures.

West Coast Challenges

Wind, waves, fog, and rocks are the West Coast’s chief natural hazards.

Wind. When the Pacific High sets in, West Coast winds follow an almost predictable pattern: calms in the early morning then a northwest wind filling in about 1000 hours, peaking in mid-afternoon as the land heats, and dying at nightfall. The same wind that blows northwest in the ocean funnels into the inlets as it enters the sounds, giving sailboats an afternoon run into the anchorages.

For sailors, the West Coast of Vancouver Island offers the opportunity to test the limits of your boat and your sailing

abilities. A two to three-week trip will likely offer at least one chance to sail in heavy weather.

Northwest winds can build to gales should an extreme high build offshore or an extreme low form inland. Those northwest gales can last a week or more. Southerly gales, however, are often over in a day, and can be preceded or followed by a day or two of calm. Listen to the VHF weather and be flexible. Protected harbors in every sound provide safe and pleasant options for waiting out a storm. Winds tend to blow stronger in the north part of the West Coast, with the highest winds between the Brooks Peninsula and Estevan Point.

If you hear “West Coast of Vancouver Island, north portion, gale warning” on the VHF weather channels, keep listening for details. You may hear, “Northwest winds 10-20 knots increasing to 15-25 except 30-40 south of the Brooks.” That means that, unless you’re south of the Brooks Peninsula (and north of Estevan Point), chances are you won’t experience gales.

Another trick to know is that in a northwest gale, much of Checleset Bay, southeast of the Brooks Peninsula, is in the lee of the Peninsula. We have spent pleasant sunny days sailing among the Bunsby Islands or the Battle Bay-Columbia Cove area while northwest gales raged offshore.

Seas. Few hazards create more fear in new sailors than ocean swells. Yet, by themselves, swells aren’t dangerous as they roll along the coast in regular formation. Ninety percent of the time, summer seas on the West Coast are less than 12 feet (four meters). But add contrary winds and current, and the seas can become “confused,” coming in multiple directions at the same time. If you are prone to seasickness, be sure to bring medications or other remedies.

Fog. The West Coast is famous for its fog. Locals refer to August as “Foggust.” Boats have spent whole months in Barkley Sound without seeing the Sound’s surrounding mountains. But fog statistics tell a more nuanced story. The BC Sailing Directions report that the percent of observations with fog at Tofino is 14.1% in May, 21.8% in July, and 29.8% in August. For Spring Island near Kyuquot, the frequency drops to 10.6% in May, 11.6 % in July, and 16.5% in August. If it’s foggy in Barkley or Clayoquot Sounds, go north. Fog also tends to clear inside the sounds.

Rocks. Rocks are numerous in all the coast’s sounds. They’re jagged, dark and can lurk just below the surface. Their presence requires careful navigation. On the other hand, they also create scenic and protected anchorages.

Preparing Your Boat

Boats of all sizes, sail and power, cruise the West Coast, but whatever their size and type, they should be designed for ocean cruising and be well maintained. Sailboats must be able to sail to weather (regardless of which direction they are going on the coast) and have a means of reefing or otherwise reducing sail. Powerboats must be able to navigate in heavy seas. Ocean swells combined with strong winds and currents can swamp a small open boat.

Navigation Equipment. West Coast fog makes radar and electronic navigation almost a necessity. They’re also useful for navigating among the coast’s rocks and islands. We also carry a full set of paper charts, which are valuable in confined waters where you would quickly need to change the scale of a chart plotter or computer program to both avoid nearby dangers and see where you are going.

Spare Parts, Tools, and Manuals. There are essentially no repair services for cruising boats between Port McNeill/Port Hardy on the East Coast of Vancouver Island and Ucluelet on the West Coast. The limited services available are oriented towards sport fishing vessels; and have limited capabilities and parts to service inboard engines, onboard auxiliary systems, and electronics.

Just as you would for going offshore or to Alaska, ask yourself, “What could end my trip? Can the machinery in question be jury-rigged? Do I have backups?” Although you may be able to have some parts shipped from Campbell River on the island’s East Coast, it’s best to carry your own spares and learn how to install them. Also, carry maintenance manuals and the necessary tools. With the right parts and tools, another cruiser may be able to help you out.

Insurance. Some insurance companies require special riders for venturing outside the Straits. Make sure to know the terms of your policy.

Communications. If you long to escape the stress of phones, email, and the daily news, cruising the West Coast of Vancouver Island is your opportunity. You’ll find cell phone service (mostly Telus and U.S. services that roam on it) in Ucluelet, Tofino, Hot Springs Cove, and much of Quatsino Sound, but not in Bamfield, Tahsis, Zeballos, Walters Cove, or any of the myriad anchorages in between. Coffee shops provide Wi-Fi, but it usually comes from a satellite at speeds urban dwellers would consider glacial. What you will find is a convenience from another era: pay phones. Every town also has a post office, but mail from the States is slow. We once waited 16 days for a priority mail package to get from Seattle to Port Hardy on the island’s East Coast.

Communications. If you long to escape the stress of phones, email, and the daily news, cruising the West Coast of Vancouver Island is your opportunity. You’ll find cell phone service (mostly Telus and U.S. services that roam on it) in Ucluelet, Tofino, Hot Springs Cove, and much of Quatsino Sound, but not in Bamfield, Tahsis, Zeballos, Walters Cove, or any of the myriad anchorages in between. Coffee shops provide Wi-Fi, but it usually comes from a satellite at speeds urban dwellers would consider glacial. What you will find is a convenience from another era: pay phones. Every town also has a post office, but mail from the States is slow. We once waited 16 days for a priority mail package to get from Seattle to Port Hardy on the island’s East Coast.

Locals use VHF radios like urban dwellers use cell phones. Channel 6 is the most common channel for local communication. Continuous VHF marine weather broadcasts and the Coast Guard (Prince Rupert) radio are available almost everywhere on the coast except inside steep-sided inlets.

Provisioning. Ucluelet and Tofino both have excellent co-op grocery stores, while Port Alice in Quatsino Sound has a full-service grocery store. In between you’ll find only general stores, whose shelves grow emptier every year. With the decline in commercial logging and fishing, and the closing of sawmills and pulp mills, the small towns have lost their base customers. You can still find what you need, but not everything you want and you may have to wait for the next town to find it. Counter-clockwise circumnavigators should provision in Port Hardy on the East Coast or Port Alice in Quatsino Sound before heading south. Northbound cruisers should shop in Ucluelet or Tofino.

Whether part of a circumnavigation of Vancouver Island or a cruise up the coast and back, a successful cruise on the West Coast requires the flexibility to change plans with the weather and the know how to take advantage of routine weather patterns.

July is the best month for cruising the West Coast. The summer high usually settles in by then, bringing northwest winds and sunshine. May, June and August are also good. Although May and June can be cloudy and chilly, winds may be lighter. August brings more southeasterly winds and the first of the autumn gales. By September, it’s time to move off the coast or hunker down in a protected harbor. The West Coast of Vancouver Island is not a winter cruising ground.

Power boaters will want to start ocean passages in early morning calms. Sailors will want to wait for the wind and take advantage of afternoon inflow winds in the sounds and inlets. Fog often comes in the morning and clears up by mid-afternoon, another advantage to sailors in afternoon departures.

If you’re heading north and the weather forecast calls for northwesterly gales, enjoy whatever sound you’re in until the wind backs off. But if the wind blows from the south, keep heading north and leave the inner-sound anchorages for the trip back south. Circumnavigators heading south down the West Coast should allow weather days for southerlies.