Words: Paul Hawran, Owner and Captain of M/Y Argo // Photos: Andy Ulitsky

The realization of our dream to round Cape Horn didn’t strike us until several days after accomplishing our near-lifetime ambition. We know many other boaters have traveled here, but this was our Mt. Everest. In fact, we were told more people summit Everest than circle the Horn on their own boat.

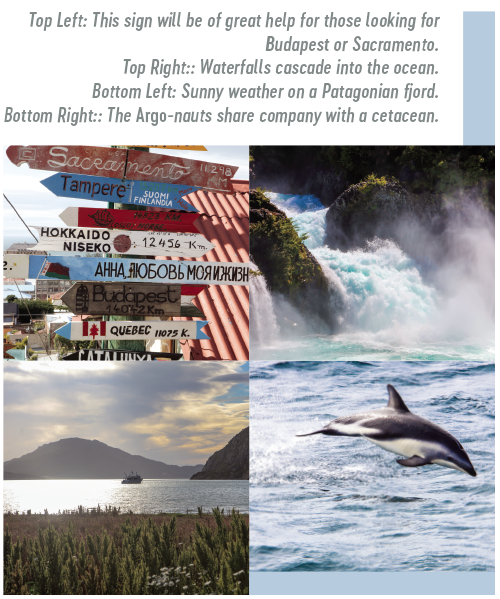

During the first phase of our adventure, described in the article A Journey Begins in Northwest Yachting‘s September, 2016, issue, we Bainbridge Islanders Paul Hawran and Andy Ulitsky described our shakedown cruise aboard the custom-built Outer Reef motoryacht, Argo, to Alaska through the Inside Passage. The successful shakedown that concluded part one of our adventure was just the beginning, for Argo travelled another 9,000 nautical miles down the coast of the U.S. to the Sea of Cortez and still further south along Central and South America coasts. Like the Greek myths of old, Argo’s journey was not only an odyssey, but echoed the tale of the Argo-nauts as we searched for our Golden Fleece – in this case, Cape Horn on our own boat, a goal we accomplished on February 5, 2017.

During the first phase of our adventure, described in the article A Journey Begins in Northwest Yachting‘s September, 2016, issue, we Bainbridge Islanders Paul Hawran and Andy Ulitsky described our shakedown cruise aboard the custom-built Outer Reef motoryacht, Argo, to Alaska through the Inside Passage. The successful shakedown that concluded part one of our adventure was just the beginning, for Argo travelled another 9,000 nautical miles down the coast of the U.S. to the Sea of Cortez and still further south along Central and South America coasts. Like the Greek myths of old, Argo’s journey was not only an odyssey, but echoed the tale of the Argo-nauts as we searched for our Golden Fleece – in this case, Cape Horn on our own boat, a goal we accomplished on February 5, 2017.

As Argo departed Puerto Vallarta last November, the hurricane season had officially ended, but the seas were still angry and unsettled along the Mexican and Central American coasts. While cruising to Costa Rica to refuel, re-provision, and get our heads into the voyage, we ran into what the weather routers called a “phenomenon” – several squalls joined together off the coast of Mexico to create a short storm that produced 50-knot winds and 12-foot seas. Perhaps it was an omen of things to come. As we passed through this phenomenon, we knew that Argo needed to pass through the Gulf of Tehuantepec and endure the Papagayo winds. But being simple-minded optimistic cruisers, we thought Rex Neptune would give us a break and provide nice seas for the remainder of the voyage.

Wrong! Perhaps it was Rex Neptune’s way of testing our resolve. Both Tehuantepec and the Papagayo winds were not favorable and were similar to the earlier storm. Once again, being naïve cruisers with a sense of immortality, we moved on. While Costa Rica offered a pleasant break, the difference between our Alaska Inside Passage shakedown and the open-ocean pounding was dramatic. There were many sleepless night runs with mysterious sounds of shifting gear as we grasped whatever handholds were available. While Argo, our custom-built Outer Reef M/Y 880 Cockpit Motor Yacht, performed like a champ, the crew became seasoned as Rex Neptune tested the limits and the crew’s fortitude. However, we were resolute in our goal of getting to and around Cape Horn.

While making headway south in the Pacific Ocean, our weather routers insisted that we take a direct heading west rather than a diagonal southwest heading to the coast of South America. Apparently, a new hurricane was forming in the Caribbean which was projected to hit Costa Rica. We headed west and then south to Chile, opening Argo to considerations of the Walker Circulation, Intertropical Convergence Zone, the Humboldt Current and the South Pacific Gyre, and their effects on El Niño/Niña patterns. For us, the result was seas running north that often produced large, narrow spaced swells and mixed seas rebounding off the coast. Argo was built specifically for stability, endurance, and performance with an efficient displacement speed providing a range of approximately 2,500 nautical miles and top end speed of 15 to 16 knots depending on local currents. In terms of running in an open ocean in desolate areas of the world, Argo was built with redundancies: twin engines, twin gensets, twin anchors and windlasses, three life rafts, as well as electronic backups to the backups.

We entered Chilean waters in early December and were greeted by a host of government officials including immigration, customs, health authorities, armada officers, the port captain, and a number of sundry officials whose tasks were to ensure the seaworthiness of Argo and its crew. Chile, with limited search and rescue operations, needs to ensure that vessels are properly equipped for the voyage through Patagonia and beyond. We later learned that Chile is not accustomed to motoryachts of an intermediate size. Any vessel between 50 and 200 gross tons is treated as a semi-commercial vessel and in certain ports require the attendance of a pilot on board. Chile also requires daily reporting at 0800 and 2000 hours and official clearing in and out of various ports through the local armada station. In fact, throughout a voyage in Chile, intermediate radio calls are made to various manned lighthouses or armada stations who track the progress of the vessel.

We entered Chilean waters in early December and were greeted by a host of government officials including immigration, customs, health authorities, armada officers, the port captain, and a number of sundry officials whose tasks were to ensure the seaworthiness of Argo and its crew. Chile, with limited search and rescue operations, needs to ensure that vessels are properly equipped for the voyage through Patagonia and beyond. We later learned that Chile is not accustomed to motoryachts of an intermediate size. Any vessel between 50 and 200 gross tons is treated as a semi-commercial vessel and in certain ports require the attendance of a pilot on board. Chile also requires daily reporting at 0800 and 2000 hours and official clearing in and out of various ports through the local armada station. In fact, throughout a voyage in Chile, intermediate radio calls are made to various manned lighthouses or armada stations who track the progress of the vessel.

Although initially such intrusion into our privacy was greeted with skepticism, we quickly began to appreciate that someone was watching us and making sure we reached our intended goal. Even for non-Spanish speaking crew, we found the personnel at the various armada stations to be extremely helpful, patient, and a true resource for Argo and its crew. In fact, even having the inconvenience of a pilot aboard as we approached a number of harbors became a great learning experience. These pilots were often former navy officers and were happy to share their knowledge and techniques to help us in our voyage south.

This may go without saying, but traveling in Chile with a motoryacht is not the same as in the United States. Marinas are scarce in Chile and the marinas we found did not provide the usual amenities to which we spoiled U.S. cruisers are accustomed. A typical marina was often merely a building with or without docks, no shore power (during our entire voyage in Chile, we never found shore power and solely operated a genset or batteries), and perhaps, if fortunate, a mooring ball. A number of times we came alongside a commercial pier used predominately by fishing or supply vessels for the many salmon farms located throughout Chile. These piers are inhospitable for motoryachts of an intermediate size (50 to 110 feet) and if we ever returned to Chile, we would avoid these piers and settle for anchoring. Occasionally, we rafted to other boats.

We entered Chile in Iquique, a lovely city whose claim to fame is a clock tower built by Gustave Eiffel, of tower notoriety. We quickly, or as quickly as we could, got out of the open Pacific to transit along Chile arriving in Valdivia before we entered Patagonia. Valdivia was settled by German immigrants following the First World War and it retains its Germanic routes. In fact, Valdivia, at least in our humble opinion, brews the best beer in the world (and we have been to the Octoberfest in Munich so we speak with certain expertise). We also docked at the oldest marina in South America, Club de Yachtes Valdivia, and although the amenities were scarce, the marina personnel made up for a perceived inconvenience.

We arrived in Puerto Montt, the first port inside Patagonia. Here, while exploring the volcanoes and spectacular lakes, we provisioned for our voyage south, including 600 feet of line used to secure Argo to trees in various “caletas” or overnight anchorages. The small towns we visited along the inside passage to Cape Horn were simply phenomenal. We celebrated Christmas in Chiloe Island where we drank pisco eggnog, visited old Jesuit wooden churches, survived a magnitude-seven-plus earthquake, and rang in the New Year aboard Argo at Melinka. We anchored in dozens of coves as we moved south, tying off with stern lines to shore whatever would hold Argo in the event of winds during the night.

The few villages along the way were fascinating. Tortel and Puerto Eden were unique in that boardwalks along the water took the place of any streets. Puerto Eden is a simple town with only 600 residents, but we were greeted like royalty, a reputation this town is known for among visiting cruisers. As we approached by dinghy, we were welcomed by the local Port Captain, local police (carabinieri), and the park ranger who escorted us through town. In fact the park ranger doubled as the only restaurant owner in Puerto Eden. He first brought us to the school for a rare Wi-Fi connection, then to his house where he prepared dinner and baked bread for us to take on our voyage, all the time refusing, unsuccessfully, any payment. This typical yet amazing attitude and giving nature of the Chilean people will long be remembered by Argo and its crew.

The few villages along the way were fascinating. Tortel and Puerto Eden were unique in that boardwalks along the water took the place of any streets. Puerto Eden is a simple town with only 600 residents, but we were greeted like royalty, a reputation this town is known for among visiting cruisers. As we approached by dinghy, we were welcomed by the local Port Captain, local police (carabinieri), and the park ranger who escorted us through town. In fact the park ranger doubled as the only restaurant owner in Puerto Eden. He first brought us to the school for a rare Wi-Fi connection, then to his house where he prepared dinner and baked bread for us to take on our voyage, all the time refusing, unsuccessfully, any payment. This typical yet amazing attitude and giving nature of the Chilean people will long be remembered by Argo and its crew.

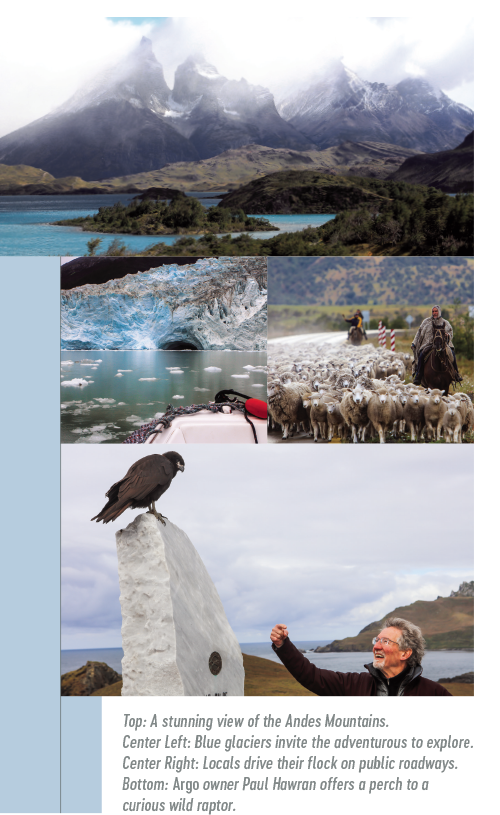

The “roaring forties and furious fifties,” referring to the latitudes, is not a myth. Once we crossed the 40th parallel, we noticed a change in climate, weather, and the natural beauty of Chile. In the forties, rainforests were jammed with trees and green beauty, and the fjords with glaciers began to appear. There was a similarity to the Vancouver Inside Passage only multiplied ten-fold. Heavy winds became the norm with sustained winds in the 30-knot range, but sometimes they climbed to 50 knots at a moment’s notice. Particularly rough seas only became an issue when transiting near or into the Pacific.

At the fiftieth parallel, winds increased to anywhere between 50 and 80 knots, and the landscape became more barren. Trees and vegetation became sparse. Beautiful by its nature, tall stone mountains shimmered in the sunlight whenever we saw the sun, or were capped by multilayered clouds. Stunning glaciers were commonplace and phenomenal sites to behold as they often met the water on our beam. On those calm days, which were few and far between, the water sparkled, but was really, really cold, and changed colors from green to cloudy white due to glacier runoff. When the sun peaked through, we’d rush out for some vitamin D exposure and welcomed it as God’s gift to us.

It was a treat and honor to cruise along the Strait of Magellan and see whales, seals, and especially dolphins, who surfed our bow waves or played with us when on the dinghy. On our last port after Puerto Natales but before Cape Horn, Puerto Williams (almost across from Ushuaia, Argentina), we were again met by the same kindness of the Chilean people we experienced throughout our voyage. We cleared through the armada station and stated our destination of Cape Horn, 90 miles further south. We were advised of the anchorages and routes to be taken as well as reminded of the distinct possibility of truly awful and unpredictable weather. While waiting for a favorable weather window, we hiked the Dientes Navarino (teeth) above the town, visited a Yagan (indigenous village), and ate local fish, scallops, and king crab.

Read the full story on Issuu

The journey was difficult and at times felt insurmountable, but with the help of the Outer Reef Yachts office (our Mission Control) and our agents and now friends in Chile (South American Super Yacht Support Services – SASYSS) who made our journey as non-Spanish speaking individuals a joy, we experienced firsthand both the unique and unbelievable natural beauty of Chile and the kindness, generosity, and openness of the Chilean people. Our associates Mike Shaughnessy and Kim McDonald also provided critical support to the mission. This journey will not go down in the annals of world history, but for us Rocky says it best, “Yo, Adrian! We did it!” -Paul Hawran