helped put Postwar Seattle on the map

There’s not a week that goes by these days without someone on some kind of boat trying to set a record for speed or distance. They may use human/wind/motor/solar power, or try some novelty event like “largest boat tie-up.” That’s an achievement that the public can easily understand! It was set by 1,651 boats on a lake in Kentucky in 2010, according to the Guinness Book of Records (surely, Seattle could take a shot at it one day!). But the record that really stands out above all others is for the fastest speed over a “measured mile” course — the unlimited world water speed record — and Seattle has already held that prize.

There’s not a week that goes by these days without someone on some kind of boat trying to set a record for speed or distance. They may use human/wind/motor/solar power, or try some novelty event like “largest boat tie-up.” That’s an achievement that the public can easily understand! It was set by 1,651 boats on a lake in Kentucky in 2010, according to the Guinness Book of Records (surely, Seattle could take a shot at it one day!). But the record that really stands out above all others is for the fastest speed over a “measured mile” course — the unlimited world water speed record — and Seattle has already held that prize.

Between 1920 and 1939, the race to win this title turned into a deadly trans-Atlantic rivalry between the USA and the UK, the speed doubled from 70 mph to 140 mph, and the drivers who survived became national heroes. After World War II, powerboat racing returned to the Detroit area, the traditional center of the sport, but was swiftly overtaken by an upstart team from Seattle. Seventy years ago they began designing the boat that just two years later would stun the sport by breaking the world record with a two-way run of 160 mph on Lake Washington.

Their boat was called Slo-mo-shun IV, a name that continues to resonate in the Pacific Northwest because it put the Emerald City in the headlines at a time when Seattle had no professional sports teams nor many claims to fame. The owner of the boat and also the driver for the record run, went on to become the most celebrated sportsman in the Emerald City for several years, and turned Seattle into the hydro-racing capital of the world. But can you name him?

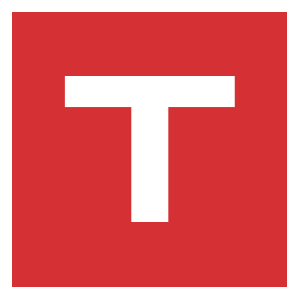

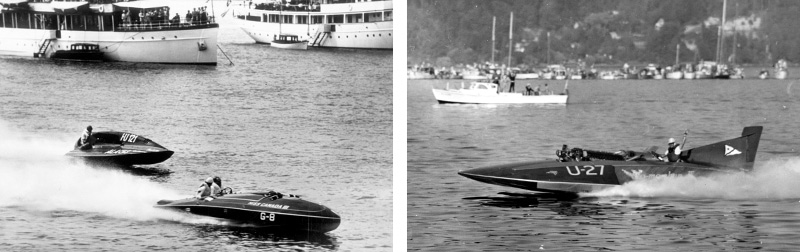

Right: During the dominance of Slo-mo-shun IV and V, 250,000 spectators would gather to watch. The draws were so large, they helped establish what became SeaFair as we know it.

Here’s a clue: in 1956, a year after he died—from a heart attack, not a boat crash—the city of Seattle named a park on Lake Washington after him. The Stan S. Sayres Memorial Park is a mile south of the Interstate 90 Bridge and, fittingly, became the site of the pits for the annual Seafair Hydroplane Races. Sayres ran a Chrysler dealership and began his racing career in fast cars. He became fascinated by the homemade raceboats he saw racing around the Northwest in the 1930s.

After the war, thousands of men returned to Washington and found jobs in the aero- and boat-building industries. Many of them had experienced the thrill of piloting high-speed warplanes and rescue boats in the war and were soon looking for ways to experience that kind of excitement in peacetime motor sports. They began to experiment with a new style of speedboat—the three-point hydroplane—and tested it in races run by the Seattle Outboard Association on Green Lake, or in the demanding annual 13-mile Sammamish Slough Race.

But Sayres was planning for a boat far bigger and faster than the Northwest had ever seen. By 1948, he had recruited Boeing engineer Ted Jones as his designer and Anchor Jensen as the builder of his new boat. Seventy years ago, they began their assault on the high-stakes American powerboat circuit. That summer, they attended the Amerian Power Boat Associatin (APBA) Gold Cup in Detroit to find out what the country’s leading teams were doing.

They learned that the traditional stepped-hull boats were being replaced with the first big hydroplanes. This gave Jones the confidence to draw a hydro that could maximize the potential of the three-point concept by supporting the boat on just the aft end of the sponsons, with the partially submerged propeller providing the third point. These are still the essential features of the hydros today, even though they are powered by 3,000-horsepower gas turbine engines that weigh around 800 lbs., about half as much as a piston engine.

Construction began at the Jensen Motor Boat Company in Portage Bay in the fall of 1948. The 28’ x 11’ hull was built of best-quality aircraft spruce and 1/2” plywood specially laid up to their specifications using mahogany veneers by the Elliott Bay Mill Company. The joints in the frames are all sandwiched with aluminum gussets and plates—as I found out when I looked inside the sponsons a few years ago. The bottom was protected by an oak keel.

All this was to ensure the hull was tough enough to withstand the pounding as it skimmed over the water at speeds in excess of 100 mph.

For power, they bought a surplus World War II Allison V-12 aero-engine that originally put out a maximum of 1200 hp at 3,000 rpm. With a 1:3 custom-built gearbox by Western Gear Works, the motor could spin the 13.5″ x 25″ two-bladed prop at a stunning 12,000 rpm. The complete boat weighed well under 5,000 lbs. and proved to be very stiff and durable—it was still winning races five years later. These super-charged aero engines were the key to hydro development for the next 40 years, and thousands of them were auctioned off by the government. With the power to push a fighter plane at over 350 mph, the sky was the limit for powerboat racing in the early 1950s.

On June 26, 1950, the Slo-Mo-Shun IV took the local media and the speed-boating world by surprise when it ran through the gates at a one-mile course on Lake Washington in a new record speed of 160 mph. This required a return run within an hour to comply with rules of the venerable Union Internationale Motonautique, the international governing body of powerboat racing based in the Mediterranean principality of Monaco.

Pushing the Speed envelope on Water

In 1955, the unlimited record was raised far beyond the reach of the propeller boats, thanks to the introduction of surplus fighter jet engines providing pure thrust. The first mark, set by Sir Malcolm Campbell’s son Donald, was 202 mph in a boat with a jet loaned from the Royal Air Force for a project of “national importance.”

It was also the first boat fitted with an enclosed cockpit for improved airflow and safety. In seven successive attempts in Bluebird K7 over the next decade, the younger Campbell raised the water speed record from 202.32 mph to 276.33 mph, culminating in 1964 when he broke both water and land speed records.

He finally succeeded in equaling his father’s achievements, becoming a popular hero in post-war Britain as he pursued his “magnificent obsession.” But in 1967 on a cold January morning in England’s scenic Lake District, he let his reputation overcome his caution and pushed the aging Bluebird K7 over 300 mph until it pitch-poled backwards. It exploded when it hit the water, killing him instantly.

That ensured his immortality as a British icon and one of the last of the old-school, upper-class overachievers.

But less than six months after his death, the record was brought back to the USA by Lee Taylor with a speed of 285 mph. He held it for a decade, then lost it to the self-taught Australian designer/builder/driver Ken Warby’s phenomenal 317.5 mph.

Taylor too was killed in 1980 going about 270 mph in his terrifyingly missile-shaped 40’ rocket boat. (“At least he died doing something he loved,” his wife said in a TV interview). Craig Arfons, from a land-speed record-breaking family, was the second American to die chasing Warby’s mark when his boat somersaulted at about 300 mph in 1989.

They are three of the dozen or more men who have died in attempts to raise the world water speed record. Mercifully, the Slo-Mo-Shun’s never killed any of their drivers, but chasing the world record looks like the deadliest game this side of Russian Roulette!

This appalling death rate makes 78-year-old Ken Warby the sole member of the world’s most exclusive club: a living water-speed record breaker. Believe it or not, his 48-year-old son hopes to break his dad’s record in the coming year. We’ll keep you posted!

Below: Bluebird K7 at Goodwood in 1960. Photo by Neil Sheppard.

The average of the two runs comfortably beat the old time of 141 mph set by Sir Malcolm Campbell in the golden age of record breaking between the two world wars. Today, this feat looks so breathtaking, I certainly thought it was the crowning moment of the season, but I was mistaken!

The morning’s events were barely appreciated in Seattle, and the world record was really just a warm-up for the team’s real goal: beating the Eastern establishment in the Gold Cup, the biggest event on the power boat racing circuit, to be held in Detroit in July. However, the Detroit News was clearly aware of the threat posed by Sayres and his team, because the fastest anyone had gone in North America at that time was 127 mph. The paper warned its readers, “Boat Going 160 mph Just A Blur–Detroit is Next Stop.”

A public subscription drive in the Seattle area enabled Sayres to take a full crew back east with the boat on a flatbed truck. When the Slo-Mo-Shun IV arrived in mid-July, Sayres told the Detroit newspaper reporters, “It’s really a backyard-built boat, a rule-of-thumb job that’s been perfected by what you might call seat-of-the-pants experiences in test runs. We want to find out if our boat is as good on the racecourse as it’s proved on the straightaway.”

The novelty of this backwoods effort quickly wore off during the first heat of the 1950 Gold Cup as driver Jones and crewman Mike Welsch guided Slo-Mo-Shun IV through a 30-mile display of unbelievable speed. The Seattle boat won at a record average of 80 mph and lapped every boat in the field. After three rounds, they had annihilated the competition and won the right to hold the next Gold Cup on Lake Washington.

To prove this was no fluke, they also went on to claim first place in the Harmsworth International Trophy race, and became the first craft ever to be timed at 100 mph in a competition around a closed course. When the victorious team returned home, they learned that the first Seafair, a centennial celebration for “the boating capital of the world,” had been a great success with parades, athletic events with small boat races on Green Lake, and also the site of the Aqua Follies in the new 5,500 seat Aqua Theater, built in a mere 75 days. The event was such a triumph that it was held the following year and is still an annual event.

The second Seafair was an even bigger hit with the first Unlimited powerboat race west of Detroit. Seattle caught “hydro mania” and never looked back. Sayres had a second boat, Slo-Mo-Shun V, sharing the boathouse of his estate, conveniently sited on Hunts Point on the east shore of Lake Washington.

The new boat was slightly faster on the turns of the race course and had a 1500-hp Rolls Royce Merlin engine, which propelled it to victory in the Gold Cup. Hundreds of thousands of spectators watched that race, which was broadcast live on King 5 TV. This gave a huge boost to Seafair, long before the Mariners, Seahawks, or Sonics came to town.

Stanley Sayres, the “Speedboat King,” was just what the sport’s promotion needed. He found himself making speeches, displaying Slo-Mo-Shun IV at fundraising rallies, and most satisfyingly receiving the backing of a newspaper campaign to keep the Slo-Mo-Shun IV at the top of the U.S. speedboat class at a cost of more than $30,000 a year.

Through the next winter, the Slo-Mo-Shun IV was tuned to perfection, until Sayres was ready to run the measured mile again. He succeeded brilliantly and drove Slo-Mo-Shun IV to 185 mph on the first leg; the return was slower, but his average was still 178.5 mph. He had now raised Englishman Malcolm Campbell’s mark by 37 mph—an impressive increase of over 25 percent.

The boat’s last big victory was a third Gold Cup win at the 1954 Seafair. In 1956, Seattle’s favorite boat crashed at 150 mph during a trial run on the Detroit River, inflicting serious injuries to driver Joe Taggart, who would never race again. The battered hulk of Slo-Mo-Shun IV was returned to its homeport, and was eventually re-built by Anchor Jensen. In 1959, it was donated to the Museum Of History and Industry (MOHAI), now on the south end of Lake Union. Footage of the boat can also be seen and heard on YouTube.

During the 1990s, both Slo-Mo-Shun IV and Slo-Mo-Shun V were restored to running condition at the Hydroplane and Raceboat Museum, headed by Dr. Ken Muscatel. In June 1999, Slo-Mo-Shun IV re-enacted her 1950 record run at Sand Point in tribute to the 50th year of Seafair with Dr. Muscatel driving. Designer Jones and builder Jensen were on-hand to witness the final chapter of the history-making saga.

Local enthusiasts of the sport are in luck, for the Hydroplane and Raceboat Museum in Kent is the nation’s only public museum dedicated solely to powerboat racing. The museum is dedicated to preserving and exhibiting important artifacts from the sport and has restored over 20 hydros. It is open Tuesday through Saturday (more info on their website at thunderboats.ning.com). In their archive, I learned that the record for a piston-powered, propeller-driven boat was increased to 200 mph in the USA in 1962 and still stands. Since 2000, the turbine-powered unlimited hydros have pushed the open propeller-driven record to 220 mph.

Read the full story on Issuu

Editors Note: Special thanks to the Hydroplane & Raceboat Museum. Paul Dorpat and Jean Sherrard of the Seattle Now & Then blog contributed information about Stanley Sayres’ automobile dealership.