Bob Perry is a name synonymous with sailing yacht design and the Pacific Northwest. We spent the day with the man and one thing became very clear: Bob Perry is drawing until he drops.

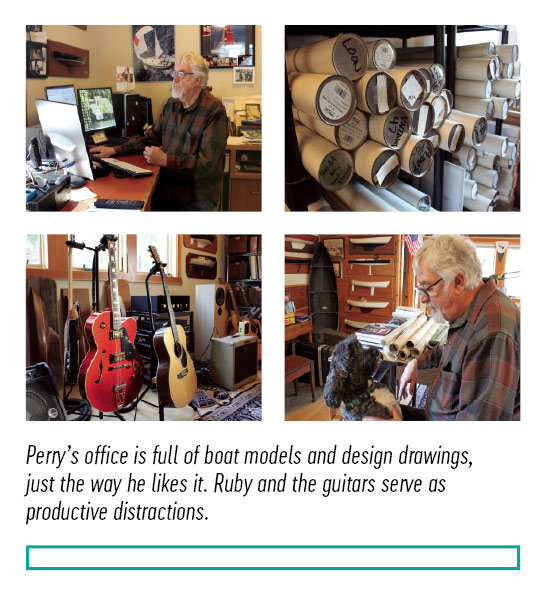

“Let’s get going, we’re late for my 8:30 appointment,” says Bob Perry the famous yacht designer as he ushers me into his Subaru Crosstrek parked in the driveway of his beach house residence. Ruby, his Portuguese water dog, scuttles around my legs and barks with impatient excitement. “Ruby goes wherever I do,” Perry says as she jumps in the back, and we’re off to the dog groomer on windy back roads that lead us through the forests of Tulalip, Washington. Opera, Verdi’s II Trovatore, plays softly on the radio. “Word of advice on life, kid, be on time. Oh dang it, I forgot my hat!” Perry huffs. We leave Ruby in capable hands and embark upon our trip to Anacortes for the true reason of my visit on this clear, frigid January day; to see what a 2017 Bob Perry-designed boat looks like.

“Let’s get going, we’re late for my 8:30 appointment,” says Bob Perry the famous yacht designer as he ushers me into his Subaru Crosstrek parked in the driveway of his beach house residence. Ruby, his Portuguese water dog, scuttles around my legs and barks with impatient excitement. “Ruby goes wherever I do,” Perry says as she jumps in the back, and we’re off to the dog groomer on windy back roads that lead us through the forests of Tulalip, Washington. Opera, Verdi’s II Trovatore, plays softly on the radio. “Word of advice on life, kid, be on time. Oh dang it, I forgot my hat!” Perry huffs. We leave Ruby in capable hands and embark upon our trip to Anacortes for the true reason of my visit on this clear, frigid January day; to see what a 2017 Bob Perry-designed boat looks like.

“For some reason people thought that, just because I moved out here, I was retired,” Perry grumbles. “I visited the doc recently and she told me I needed to work less and relax. Well, when I work, I relax,” he chuckles. “I told her I relax at the boatyard, and she said to do more of that, so here we are.” The new boat Bob Perry and I are travelling to see, unofficially dubbed the Bulletproof 43, is under construction by James Betts Enterprises, Inc. in Anacortes as per Perry’s design. Four hulls are currently under construction and all of them are spoken for. We talk about the project, a clear view of a snowy Mt. Baker to our right as we maintain our northerly bearing to the shipyard.

“Basically, we’re making the Humvee of performance cruising yachts,” says Perry. “We’re taking an old, timeless look and bringing it up to 2017 standards.” The Bulletproof 43 is genetically similar to the Bristol Channel Cutter, with features like the bowsprit and deck-mounted butterfly windows invoking an Old World spirit, yet most of the yacht is made of carbon fiber. The hull shape, while a full keel, is certainly modified in the more modern style to reduce wetted surface area. Essentially, the Bulletproof 43 is designed to be a beast of a vessel that thrives during extended offshore passages and outpaces other cruisers of her size.

In a lot of ways, a boat like the Bulletproof, with one foot in the old and the other in the new, is right up Bob Perry’s ally. Perry’s storied yacht design career was off with a bang after the introduction of his Valiant 40 sailboat in 1973, a yacht that gave birth to the entire “performance cruiser” family so common today. Where the categorical line between heavy, full-keeled, and slow ‘round-the-world cruisers and light, fin-keeled, and fast ‘round-the-buoys racers used to be uncompromising, Perry led the charge to blend the two worlds. The Valiant 40 combined what was then a modern International Offshore Rule (IOR) racing shape under the waterline with a classic Scandinavian double ender above-waterline design. The Valiant 40’s place as a yacht-design game changer is immortalized with a successful production run of 200 hulls, several evolutions including the Valiant 42 that continued into the 21st Century, the dozens if not hundreds of emulators, and an induction into the American Sailboat Hall of Fame as the Cruising Sailboat of the Decade in 1997. A well-kept Valiant 40 is still about as valuable as it ever has been on the resale market, a long-term accomplishment that all yacht designers yearn for. Fast forward to 2017, and it’s no surprise that Perry would be keen to apply the new and modern with the traditional and heritage-rich.

In a lot of ways, a boat like the Bulletproof, with one foot in the old and the other in the new, is right up Bob Perry’s ally. Perry’s storied yacht design career was off with a bang after the introduction of his Valiant 40 sailboat in 1973, a yacht that gave birth to the entire “performance cruiser” family so common today. Where the categorical line between heavy, full-keeled, and slow ‘round-the-world cruisers and light, fin-keeled, and fast ‘round-the-buoys racers used to be uncompromising, Perry led the charge to blend the two worlds. The Valiant 40 combined what was then a modern International Offshore Rule (IOR) racing shape under the waterline with a classic Scandinavian double ender above-waterline design. The Valiant 40’s place as a yacht-design game changer is immortalized with a successful production run of 200 hulls, several evolutions including the Valiant 42 that continued into the 21st Century, the dozens if not hundreds of emulators, and an induction into the American Sailboat Hall of Fame as the Cruising Sailboat of the Decade in 1997. A well-kept Valiant 40 is still about as valuable as it ever has been on the resale market, a long-term accomplishment that all yacht designers yearn for. Fast forward to 2017, and it’s no surprise that Perry would be keen to apply the new and modern with the traditional and heritage-rich.

“You know, science and engineering have done some pretty great things with production yacht design,” muses Perry aloud. “But it’s come at a cost in a way. Sailboats are starting to look more and more alike because we’ve figured out that certain design features simply perform better. It’s as if the circle of what is acceptable to design in production boats has gotten narrower and narrower, so now it seems as if new production boats pretty much all look alike. All those great idiosyncrasies are going away. Back in the day, boats really handled differently. There were always some real pigs out there, but there were also some pretty creative designs and you just don’t see anything like it anymore.”

The sentiment is reinforced with what Perry’s meat and potatoes are these days: custom builds. Fortunately for Perry, his clients tend to seek him out specifically to tackle projects that are more up his alley. Perry’s clients turn away from the production line and seek him out for original boats because they want those idiosyncrasies, that elusive flair that can be hard to find on the factory line. Perry’s profile of custom builds speaks for itself. Recent builds like his bespoke Francis Lee, a double ender, very narrow, all-wood “old man’s day sailor” built for a client, comes to mind.

“From a pragmatic standpoint, there are plenty of reasons not to go with a double ender,” says Perry. “There is less space aft on deck and less space below for stowage and engine access. But you know what? If you like it, go for it! Beauty and personal appeal are great reasons to go for a design.”

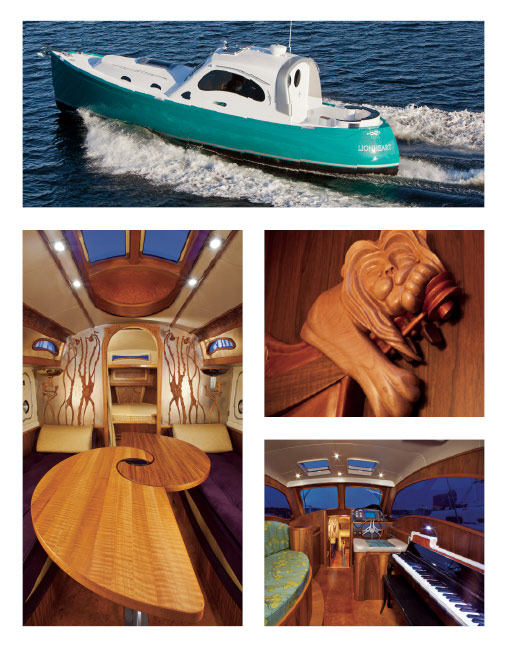

Bob Perry’s record again speaks for itself. We’re talking about the guy who not only turned the sailing yacht world on its head, but also designed Paul Allen’s mini-sub. Other designs with features tailored to personal preference over sometimes cold-hearted efficiency include the private motorboat Lionheart Concerto. The double ender’s look was to emulate a Bugatti Type 57 Atlantic sports car, and Perry whipped up “dog bone” windows as an inspired take on the project. A concert piano is built-in below, and the instrument is hooked into a speaker system that invokes a sort of aquatic Phantom-of-the-Opera vibe.

Bob Perry’s record again speaks for itself. We’re talking about the guy who not only turned the sailing yacht world on its head, but also designed Paul Allen’s mini-sub. Other designs with features tailored to personal preference over sometimes cold-hearted efficiency include the private motorboat Lionheart Concerto. The double ender’s look was to emulate a Bugatti Type 57 Atlantic sports car, and Perry whipped up “dog bone” windows as an inspired take on the project. A concert piano is built-in below, and the instrument is hooked into a speaker system that invokes a sort of aquatic Phantom-of-the-Opera vibe.

“If I’m going to do a powerboat, it’s got to be one that I think I can do the best, which almost by definition means it’s going to be unusual,” says Perry with not-so-subtle pride. Anacortes nears as we navigate a gold-colored sea of icy farmlands. He scans the scenery. The Trumpeter Swans are migrating through and he likes to spot them, and sometimes even pulls over and to watch them if they are close to the road. “There are plenty of ways to be miserable in life, but designing your boat shouldn’t be one of them. At the end of it all, designing a yacht is a very intimate business. You just have to be friends, or at least friendly, during the process, and believe in what you’re doing.” We pass by a bevy of swans picking at dead grass on a field. “Beautiful design,” Perry says of the swans.

“Alright, here’s the deal. I know once we get to the boatyard, you’re going to start asking, ‘Why this?’ and ‘Why that?’ about my design decisions,” says Perry after a lull in the conversation. “At the end of the day, I have one answer for you, ‘The client wanted it that way.’ I never view my role as forcing my preferences on anybody else, rather I do my best to sell what I think is a good idea.”

We park at the yard and Bob Perry’s demeanor noticeably relaxes, almost as if he was holding in a breath until now. I follow him into the first of two expansive shops where the Bulletproof 43s are housed. He knows every one of the workers who walk by, and easily strikes up a conversation with each of them to introduce me. We end up in an office and I meet Neil Racicot, the head designer and project manager who digitally interprets Perry’s two-dimensional designs into three-dimensional renderings on his computer. The two banter about design elements and agree and disagree in a lighthearted manner. Perry’s attitude is collegial as he rolls up a newly printed design drawing and tucks it under his elbow as we leave the office and enter the expansive shop.

“You’re not supposed to know about this design yet,” he says of the paper under his arm with a conspiratorial grin. Two of the four Bulletproof 43 hulls sit before us, one with the deck and hull assembled and the other still in parts. An undeniably Willy Wonka factory experience ensues as Perry points out the sights as workers, many wearing bunny suits, rebreathers, and gloves, hunch over boat components and practice their trades. The building process for the Bulletproofs involve isolating parts of the design and building them modularly for assembly. The deck of #3 sits near her upside down hull where the modified full-keel aims proudly at the ceiling. The keel is a mix of carbon fiber and glass-reinforced plastic (GRP, aka fiberglass) with a total thickness of 1 ¼ inches and, conceivably, could be bulletproof.

“This ain’t your grandpa’s boatyard,” Perry says as we explore. “These guys make me look good.” The traditional mindset plays out with a few of the design features as one looks closer. Old-school knowledge says that through hull fittings are a liability, so there simply are none here. Instead, a bespoke sea chest system is used. Overall, the boat is undeniably modern, and carbon fiber building methods allow for some very strong features. For example, there simply isn’t a bolted joint between the hull and deck because with carbon fiber building methods, the entire boat is ultimately cast as single complete piece.

“This ain’t your grandpa’s boatyard,” Perry says as we explore. “These guys make me look good.” The traditional mindset plays out with a few of the design features as one looks closer. Old-school knowledge says that through hull fittings are a liability, so there simply are none here. Instead, a bespoke sea chest system is used. Overall, the boat is undeniably modern, and carbon fiber building methods allow for some very strong features. For example, there simply isn’t a bolted joint between the hull and deck because with carbon fiber building methods, the entire boat is ultimately cast as single complete piece.

We stroll over to the other shop where hull #1 sits, the nearest to completion. Her tentative launch date is set sometime in April, and there is a palpable buzz as workers climb up and down scaffolding built around where she sits on struts. Perry and I step aboard her deck and down the companionway to check out what will eventually become a nice salon, galley, and navigation table. Two modest sea berths are laid aft, one on either side of the accessible engine space, likely the most comfortable in rough seas. She’s definitely less beamy than the average production boat of her size. The traditional wisdom of narrow-beam seaworthiness prevails.

“You know, I don’t usually get to come up here,” says Perry. “Ruby goes everywhere I go, and I know if she followed me in here she’d mess something up.” We leave around lunchtime after saying our many goodbyes. Perry knows a place where we can grab a sandwich and a beer, and we end up at the bar in the La Conner Pub and Tavern.

“Good afternoon, Bob!” The bartender smiles as she takes our lunch orders. We sip on Manny’s Pale Ales while we wait for the food. Perry changes his order, for the meatloaf special is out, so he goes for a sandwich special with a side of coleslaw. I ask what it feels like to see a boat from inception to launch. Is it an adrenaline rush? A quiet moment of reflection?